Unsung America - Maine Journal: Like Father, Not Like Son

Text von David Sokol

Washington, DC, USA

10.12.08

David Moser is product development manager of Thos. Moser Cabinetmakers

As a teenager, I remember flipping through the back pages of The New York Times Magazine and stumbling across advertisements for Thos. Moser Cabinetmakers. The focal point of each announcement would be an example of the furniture studio’s work, and inevitably it would exemplify Shaker style and craftsmanship.

Imagine my surprise, then, when I decided to refresh my knowledge of Thos. Moser for our Unsung America road trip. To be sure, Shaker, Arts and Crafts, and other time-tested versions of simplicity were still for sale. But so were furnishings that had interpreted historical modernism. The undulating Chaise is a clear descendent of Alvar Aalto’s 39 Chaise Longue. If the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman were to mate with Vladimir Kagan's Contour Low Back Lounge, its child—delivered by Hector Guimard—could be the Kinesis Collection. Although the Auburn, Maine–based Thos. Moser was still focusing on wood as its primary material, its artisans had transformed the medium—molten, electric, anthropomorphic—beyond original recognition.

It turns out that David Moser was responsible for both the advertisements and, later, Thos. Moser’s leap from orthogonal tradition to organic contemporaneity.

He was in his early 20s by the time he was writing ads, so he only witnessed the company’s previous growth spurt. His parents Tom and Mary were living like unreformed hippies in Maine, divvying up cooperative foodstuffs on a semiweekly basis and working on anything from house construction to furniture. By the 1980s they reasoned that they “could make a go at furniture as a viable business,” David Moser says, adding that “we needed some kind of design franchise.” Tom took an interest in the Shaker community in New Gloucester, Maine, and created a line of furniture inspired by their ethos.

“That took us all the way to 10 or 12 years ago, when we had about 60 employees and a couple of showrooms around the country,” David Moser says. His father was not producing new furniture then, rather focusing on other aspects of the maturing business. Many others, however, were doing just that. The company disseminated its designs through catalogs and a growing network of showrooms, and it had also authored a number of how-to books commissioned by a friendly publisher. David Moser recalls: “By our own invitation, a whole myriad of cottage-industry woodworkers started building our designs. They could, because they were largely rectilinear, and so they did. I wouldn’t say our Shaker-inspired designs were sophomoric, but they were executable by anybody with relatively talented hands and access to ubiquitous woodworking equipment.”

By 1998, even larger companies were treading into Moser territory, and sales patterns were beginning to reflect that easy replication. That year brought on a major shift in response. The Mosers hired its first marketing director, and David, who had been opening showrooms and writing copy, launched into design work.

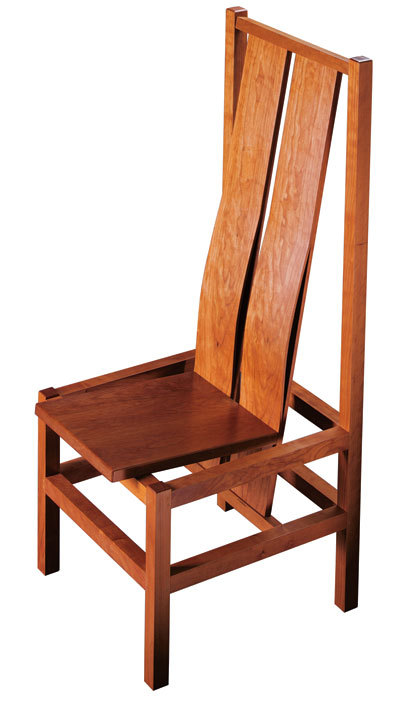

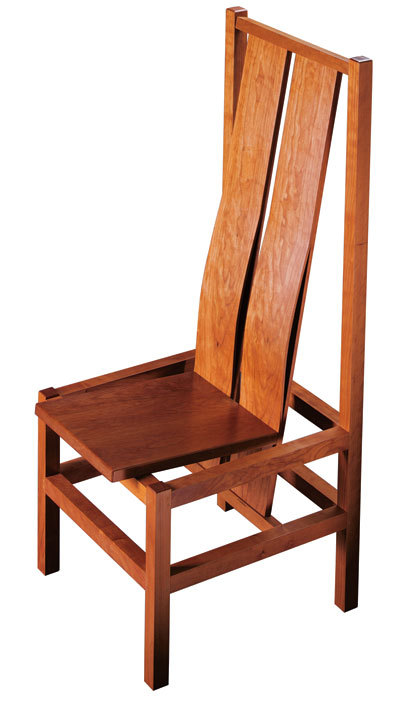

“We never went to RISD, but we all have this ability to express ourselves creatively,” Moser says of his design chops. (He and his three brothers all apprenticed at the Thos. Moser bench.) Even before 1998 he was adding to his father’s collection, embracing more recent aesthetics and technologies: The high-backed Washington Square chair evokes Frank Lloyd Wright or Charles Rennie Mackintosh; to create the bowfront shape in the Crescent series woodworkers employed lamination, a company first. Taking on the full-time designer role, Moser, now 44, has departed even more dramatically from the Shaker vernacular. The limited-edition Alienation Bench quite literally twists that vocabulary, the crest of its backrest resembling a Möbius strip snipped off at an end. The solid cherry Vita Chair and Ottoman jauntily pay homage to Mies van der Rohe.

Despite their fierce resolve and loyalty, staff woodworkers initially greeted the youngest Moser’s design changes with a certain leeriness. “As an artist it was important to challenge myself and give myself expression in form,” Moser says. “That paradigm shift became very difficult, and it required not a little bit of capital investment, either. We had fairly ubiquitous machinery, and this required us to learn new skill sets.” Thos. Moser ordered the first five-axis CNC router in the state, for example.

Resistance metamorphosed into nurture and pieces like Alienation and Vita, or Chaise and Kinesis, have since sprung to life. And consumers have sprung into action, approximately quadrupling the company’s revenues over a short span. Perhaps girded by the enthusiastic marketplace, “I would imagine that in the years to follow you’re going to see much more challenging work from me, because I don’t care to just continue redesigning right-angle furniture,” Moser envisions. He does note, though, a steadfast loyalty to the “core materials” of wood, clay, leather, and glass. He foresees another parameter for his work: “I want to protect ourselves from the hubris of saying we create new things. I am inspired by everything I see, but I reach back into historical form and I bring elements forward, adding a contemporary interpretation of it and my own implied intellectual value. I’d never be so arrogant to say creations we come up with don’t have historical antecedents. Those antecedents give them credibility.” So, too, does Maine craftsmanship—and here it should be pointed out, too, that Thos. Moser alumni form their own constellation of at least 30 new woodworking studios. “The responsibility of the designer is greater than it’s ever been,” David Moser says, a statement that refers to resource consumption but which could just as accurately apply to supporting local talent. Without doing so, Moser’s inventive visions may have never materialized.

Welcome to Unsung America. Inspired by Alice Rawsthorn’s critique that the U.S. lacks powerhouse furniture designers, this column observes the local communities and conditions supporting a variety of design disciplines. The “Maine Journal” entries are the first in a state-by-state exploration. Next time: Pop! goes innovation.