Medium Rare: Architonic at Design Miami Basel 2010

Text von Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Schweiz

24.06.10

Described by its organisers as 'the pre-eminent global forum for collecting, exhibiting, discussing and creating design', Design Miami Basel, the annual European get-together for those who like their design a touch on the exclusive side, put on a robust show this year. With the love-it-or-hate-it market for limited-edition design and one-off pieces clearly here to stay, Architonic spent some serious fair time with three of the scene's leading international design gallerists.

'The most of the best to the greatest number of people for the least.' So goes Charles and Ray Eames' old design principle. You'd be hard pushed, however, to find such a democratic design mantra, derived as it is from early 20th-century modernist ideology, being chanted at Design Miami Basel, the annual European installment of the international limited-edition-design show. If the Eameses subscribed to the notion of design as something that can, and should, improve our everyday lives, then a trade-fair hall full of wealthy design collectors, curators and the odd celebrity poring over exclusive design pieces that, for the most part, eschew industrial-design processes and which come with a hefty price tag, is about as far as you can get from this belief.

'Secretaire' from Maarten Baas's 'Grey Derivations' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

'Secretaire' from Maarten Baas's 'Grey Derivations' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

×Much has been written about the phenomenon of limited-edition design / design-art / one-off design. (Delete as required.) Since Design Miami was launched in 2005 by unfeasibly young entrepreneur Ambra Medda and Miami-based international property mogul Craig Robbins, the market for high-priced design collecting has continued to grow. Opinion has been divided from the start, however. Does this type of design activity, insofar as it sits outside the system of mass production, afford the designer greater creative freedom and, therefore, result in more experimental and challenging work? Or is its artificial limiting of the number of times a design is produced, its fetishising of rarity or uniqueness, a cynical, get-rich-quick strategy for designers who've grown tired of regarding the lucrative art market with envious eyes?

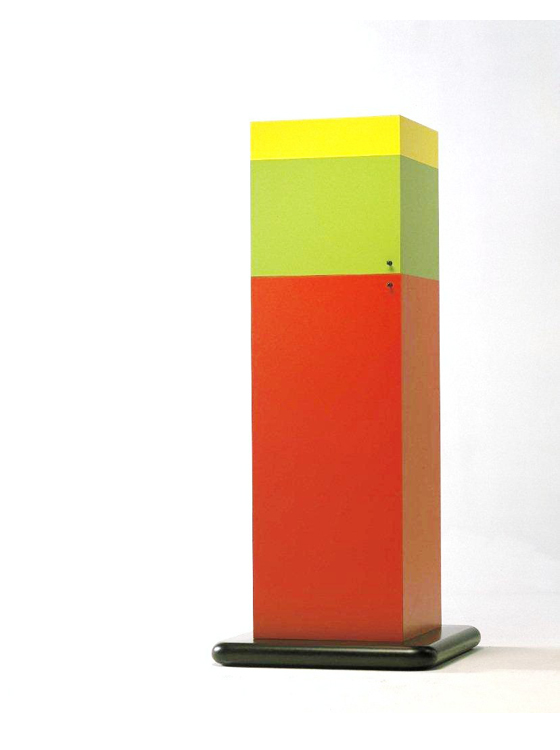

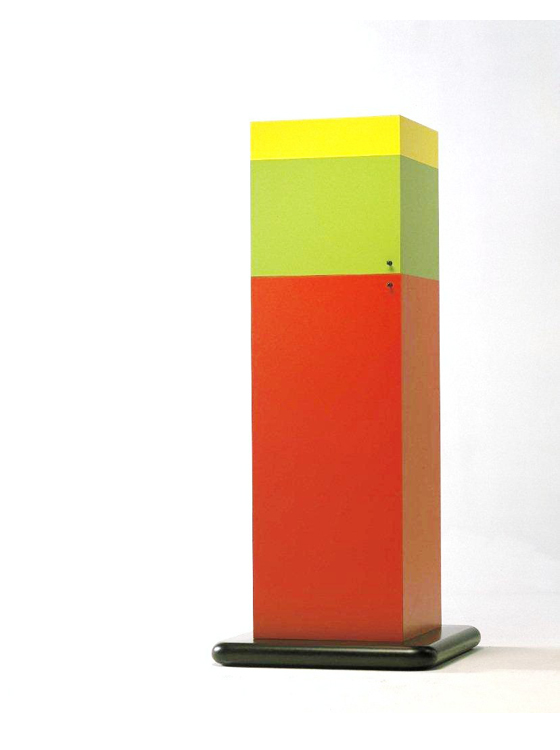

'Hotel California' cabinet by Ettore Sottsass, 1966, shown by David Gill Galleries; image Thomas Brown

'Hotel California' cabinet by Ettore Sottsass, 1966, shown by David Gill Galleries; image Thomas Brown

×I'll level with you. I was always one of the cynics. I found it hard to view limited-edition design in terms other than purely financial ones. The problem for me was that design was precisely not art. Instead of the metaphoricity, the figurativeness of art, design was all about having a clear utilitarian function, and, as such, couldn't (or shouldn't) be commodified in the same way. (Now, of course, design can sometimes function on a metaphoric level, too, and art can be described as functional. But that's a discussion for another time.) Yet, having spent time at this year's Basel show with three of the international design scene's most articulate and, it has to be said, charming design gallerists, my position has changed somewhat. A Damascene conversion this hasn't been, but, rather, a realisation that policing the definition of design doesn't do anyone any favours.

Milan-based design gallerist Rossana Orlandi; image courtesy of Spazio Rossana Orlandi

London-based David Gill could be described as the godfather of the design-gallery scene. Having shown and, of course, sold limited-edition pieces since the mid-1980s, a long time before the advent of 'design-art' as a label or trend, he's seen it all. Experience is something that grande dame of the Milan design scene Rossana Orlandi also has in spades. If you haven't visited her spazio on the Via Matteo Bandello, a warren-like collection of galleries that feature carefully selected and beautifully presented objects, then you must. Based in Geneva, new-kids-on-the-block Mitterrand + Cramer may, in contrast, have only been in the design-gallery business for a couple of years (although Edward Mitterrand has been selling and advising on art for a lot longer), but they have, in that short space of time, created a collection of pieces by big-name designers like Tom Dixon, Maarten Baas and Arik Levy that is, whatever your take on this rarefied design world, extremely impressive. One thing unites all three gallerists: a passion for what they do.

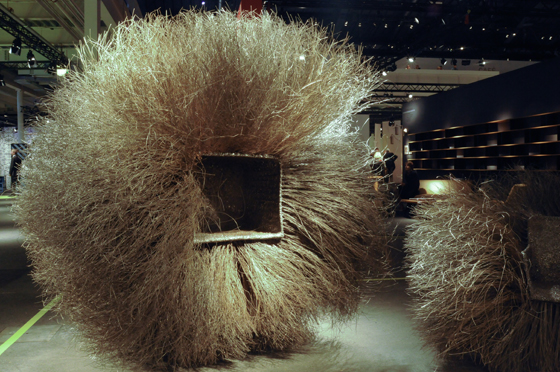

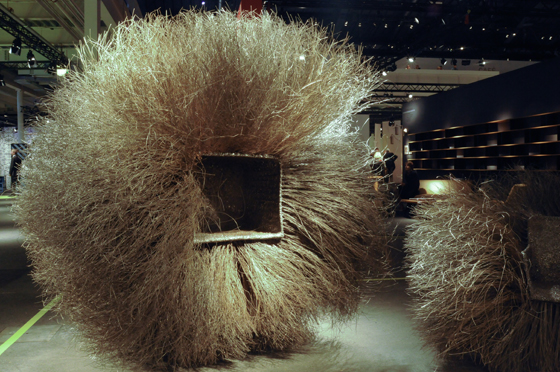

'The Bush of Iron' by Nacho Carbonell, shown by Rossana Orlandi; image Tatiana Uzlova

Rossana Orlandi puts it quite simply: 'I love what I show.' For the Milanese matriarch, it's about connecting on an emotional level with the work that she presents, living with it. Is she not business-minded then? 'No,' she laughs. 'Unfortunately, I'm not. But in the end, I'm right. If I think that something is gorgeous or amazing, I'm sure we'll sell the piece, even if it's not straight away. You need time. But I just fall in love with things.' For David Gill, who, as one of the vanguard of the limited-edition-design market, has seen a raft of competing design galleries emerge over the years, passion is what gives one a business edge: 'I think you have to know who you are and what you do. And truly to believe in it,' he says. A clear vision is something that Edward Mitterrand also possesses. Having run a contemporary-art gallery in Zurich for many years, which recently moved to the city's hip Industriequartier, his venture into design with partner Stephanie Cramer was, from the outset, singular in its approach. 'We wanted to start with big names and start with producing pieces, to establish our legitimacy for this business and for us. To be recognised immediately. I really like design and the Geneva gallery was an opportunity to be freer than the strict art programme we have in Zurich. But, it's not been an easy time to do it.'

Scale models of the 'Diversity' collection by Nacho Carbonell, shown by Rossana Orlandi; image Tatiana Uzlova

Scale models of the 'Diversity' collection by Nacho Carbonell, shown by Rossana Orlandi; image Tatiana Uzlova

×Not been an easy time? Maybe it's the fact that Mitterrand is half British which contributes to such understatement. As we continue to reel from the effects of a global economic downturn, could there have been a worse time to get into the high-end-design game? 'Yes, it's been tough,' admits Mitterrand. 'All this investment is tough. That said, we arrived late in this, so we didn't have to make all the crazy investments that were going on before and set prices too high too fast. We don't get involved in projects that are too expensive for us.' Orlandi is philosophical about the recession: 'The crisis has been very strong. But it's changed the way we think and live. It makes you think: "OK. What shall we do now?" And you find a new way. But it's still a struggle.' Gill, too, is far from despondent about the performance of the market. 'The fact that it's been affected, that things have slowed down,' he argues, 'doesn't mean things have stopped. Collectors are still making their choices.' Those choices aren't being made as readily as they once were, as far as Orlandi is concerned. 'Collectors are more cautious. In fact, the richer they are, the more cautious they are. Because they're rich. They still spend, but think about it more.'

David Gill, who opened his London gallery in 1987; image courtesy of David Gill Galleries

There's nothing like a recession to place that purchase of a limited-edition design piece out of reach, it seems. But, according to Mitterrand, the wheat-from-chaff sorting that the downturn has affected helps increase acquisition opportunities for the most committed of purchasers (if, of course, they have the wherewithal): 'The real collectors are still here because huge amounts of money are available, but not in so many hands now. You still have people with a lot of money who will buy whatever they want, but you have less people who have enough to buy what they want without understanding what they are buying and at crazy prices. The real collectors have more space now.'

'Port Lights' by Alexander Taylor, shown by David Gill Galleries; image Antony Makinson

So, things are looking up. But surely it's about more than just selling? If it weren't, then you might as well sell, well, something else that isn't such a hostage to the vicissitudes of the global economy. I ask the three gallerists what the creative process is of working with their designers on such exclusive projects. How involved do they get in the genesis of a piece? Do they themselves have a creative input? Orlandi is emphatic in her response: 'I am for young designers. It's in my spirit,' she says. 'I like the freedom with people with whom I work. We can talk about "This is more saleable. This is less saleable." But I leave people to their creativity. I didn't know, for example, what Nacho Carbonell was going to be bringing here to Basel. Just the concept. Designers need to be free. It's so important for their creativity.' Does that relinquishing of control mean less stress? 'Absolutely, ' she answers. Orlandi's relaxed and open approach means that she acts as much as a facilitator of creative work as a director of it. 'My house is open to all designers. I like to be open,' she explains. 'And I like to share. Since I was young I always shared things. For me, it's very important not to look at your small garden, but to share everything. This is my way of working.'

Edward Mitterrand and Stephanie Cramer, founders of the Geneva-based gallery Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

Edward Mitterrand and Stephanie Cramer, founders of the Geneva-based gallery Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

×You could probably describe Gill as a true design patron. 'I think it's important that I get involved with the work itself,' he says. 'It's almost like commissioning. When we discuss an exhibition, there is a dialogue in terms of what the pieces are going to be and why they are being made, to the point of which materials and finishes. I'm not just a gallery. I'm actually involved in the production. I have to make sure everything is perfect down to the millimetre.' Gill doesn't see his position as compromising his designers' creative independence, however. 'I don't want to take anything away from their creativity,' he maintains. It's clearly a modus operandi that works well for him. A Garouste and Bonetti piece of his recently achieved €127,000 at auction.

'Dressoir' from Maarten Baas's 'Grey Derivations' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

'Dressoir' from Maarten Baas's 'Grey Derivations' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

×By contrast, Mitterrand is less inclined to get involved in the fabrication of the pieces his gallery shows. Commissioning isn't a word that he would use to describe its activity. 'We've really approached it exactly the same way we've been working with contemporary artists. And I think that's what the designers have liked. We called them and just said "We would like to work with you." So, they aren't really commissions. The designers we work with are in complete control of the line of production. We didn't want to be involved at all with finding manufacturers or things like that.' So where does Mitterrand stand creatively in relation to his designers? 'Well, if I didn't like an idea, I would say so diplomatically. But it wasn't censorship. It was more a discussion. It was rare that I said I didn't like something all. I would just not say anything and they understood. Sometimes you feel impressed by big names, but we feel we are strong enough and straightforward enough to get it right.'

Atelier Oi's 'Danseuses' ceiling fans, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

Atelier Oi's 'Danseuses' ceiling fans, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

×It's clear that, whatever the level of creative dialogue between designer and gallerist, limited-edition design offers an alternative creative space for designers, who might be unable to realised certain projects within the industrial-design system. 'It's about taking the designers as far as possible out of the industrial-design world,' maintains Mitterrand. 'There are plenty of things from Vitra or B&B that I love, but we are creating something new, something that didn't exist before.' Orlandi, who showed Naoto Fukasawa's beautifully designed and industrially produced 'Shelving System' for Artek at her space during this year's Salone del Mobile, doesn't see a contradiction between mass-manufacturing and limited editions or one-off pieces when it comes to design. 'I like to be alive,' she says with typical passion. 'And a house needs to be alive. This means living in a house that has unique pieces, but also industrially made things. It's just important that everything tells a story.'

Architect Zaha Hadid's 'Stardune 02' table, shown by David Gill Galleries; image Antony Makinson

For Gill, gallerists provide creative opportunity, which can be particularly beneficial for younger designers. 'Gallerists are really on the front line,' he says. 'We are really among the first to see who's out there. They create with the means they have, but to take this to a production level they really need to be working with a gallery.' Such creative benevolence is, of course, subject to some serious business conditions. But, nonetheless, work emerges from the creative union between gallerist and designer that is truly conceptually strong and meaningful. 'There's an energy,' Gill continues. 'It's like a renaissance happening now. It began a while ago, but it's really growing.'

Studio Makkink&Bey's 'Dinner for Two' from the 'Repackaging' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

Studio Makkink&Bey's 'Dinner for Two' from the 'Repackaging' series, shown by Mitterrand + Cramer; image courtesy of Mitterrand + Cramer

×Design Miami has developed a very successful brand out of such energy. In spite the show's superlative-spouting PR machine ('the pre-eminent global forum for collecting, exhibiting, discussing and creating design' and 'an undeniable force' are just two examples of the hyperbole it likes to indulge in), Design Miami, or rather the galleries who show there, play an important role in the ongoing narrative of design. For they serve, in the specific way that they negotiate design, the way they affect its production and exhibit it, to question the very definition of design itself.

Barnaby Barford's 'I Love Noddy' mirror, shown by David Gill Galleries; image Antony Makinson

In 2004, during her tenure as director of the Design Museum in London, design critic Alice Rawsthorn set the cat among the pigeons by including an exhibition on Constance Spry, the mid-century flower arranger extraordinaire, in the institution's programme. Terence Conran, founder of the museum, was not impressed, writing in the 'Guardian' newspaper that Spry was 'off the radar'. The vacuum-cleaner designer and manufacturer James Dyson went one step further by resigning as chairman of the museum. But Rawsthorn's decision to feature Spry's work in the hallowed space of the Design Museum did something very important: it worked to challenge the very meaning of design. The strong reactions it provoked from proponents of design as only ever an industrial process demonstrated, if anything, that design's definition is never, and never should be, self-evident and assured. Design Miami's gallerists, like Rawsthorn, remind us that design, in its function as an agent for change, is itself not immune from the forces of change. Now, that's got to be good.

.....