Making an Exhibition of Ourselves: Architonic deciphers some of Expo 2010 Shanghai's architectural offerings

Text von Tim Abrahams

London, Großbritannien

15.05.10

No form of architecture is perhaps as loaded with rhetoric as the expo pavilion. With hundreds of countries currently jostling at the Expo 2010 in Shanghai to attract visitors into their little piece of home, Architonic takes a look at what's at stake in such an enterprise in terms of representation and national identity.

Expo 2010 in Shanghai is an orgy of representation. Each of the 239 pavilions, built in a park situated on a peninsula the size of Gibraltar, which juts out into the Huangpu River, has been designed to represent a political entity – usually a nation, but occasionally a city or an international body. Often these buildings represent these entities through a very clear symbolism, highlighting an aspect of the nation in question, in order to promote investment in that country or to encourage trade. Given the complexity of the entities represented, these three-dimensional representations are often very much at odds with the reality.

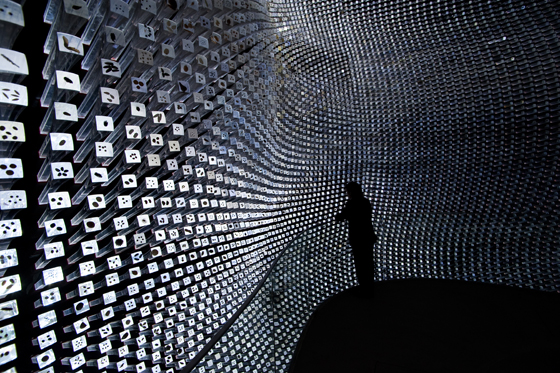

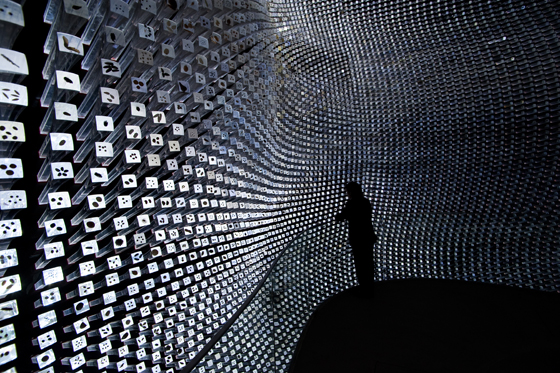

'Seed Cathedral' by Thomas Heatherwick functions as the UK's pavilion at Expo 2010 in Shanghai

Take the Israeli Pavilion, for example. It is composed of two streamlined buildings hugging each other, like two clasped hands, linked in a friendship that we are unlikely to immediately associate with that troubled land. Incongruous design isn't unique to national pavilions, however. The entrance of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent pavilion is designed to look like a white tent, an image of disaster relief that sends a message that the ICRC is active and in the field, glossing over the fact that it is also an established international institution with 12,000 full-time employees worldwide and an annual budget of 1 billion Swiss Francs.

Inside the British Pavilion (aka the 'Seed Cathedral' by Thomas Heatherwick) at the Shanghai expo

When design promotes a single narrative, it often fails. This simple legibility is often a product of competition, national bodies desperate to grab the attention of visitors at the expense of one's rivals. The exhibition movement was born in the mid-19th century and grew parallel to, and often as an expression of, rising nationalism in Europe, which was eventually to prove so calamitous. At the Venice Biennale in 2008, Anne Lacaton, a member of the jury for the Belgian Pavilion, expressed why she was personally uncomfortable with the whole premise of the expo. ‘The archaic notion of having countries compete against each other in a nationalistic contest as they did in the 19th century world exhibitions is no longer appropriate today,’ she said.

Each of the UK Pavilion's 7.5-metre-long acrylic rods, which draw daylight into the interior of the structure, contains a specimen from the Millennium Seed Bank in London's Kew Gardens

Each of the UK Pavilion's 7.5-metre-long acrylic rods, which draw daylight into the interior of the structure, contains a specimen from the Millennium Seed Bank in London's Kew Gardens

×And yet this competitive aspect persists. Part of the brief from the British Council, the client body for the British Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo, was that it should do well in the in the public vote for the best of the 239 pavilions on show. And it's a part of the brief that Thomas Heatherwick’s design addresses perfectly. The 'Seed Cathedral' is a cube that is pierced with 60,000, 7.5-metre-long acrylic rods, which sway gently in the breeze. A stunning object in an undulating landscape, it also delivers its point: quite literally. On the interior, the end of each rod is embedded with a specimen from the Millennium Seed Bank at London's Kew Gardens. It is hoped that the accumulative effect will be a subtle testament to the scope and excellence of biodiversity research in the UK. ‘We have a long history of bringing nature into our cities. We pioneered the world’s first ever public park and the first major botanical institution, the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew,’ says Heatherwick.

Danish Pavilion at Expo 2010 in Shanghai, designed by Bjarke Ingels; photo Iwan Baan

Even in a globalised world economy, competition between nations is still at the core of our political structures, not to mention our financial ones. The capacity of governments to control flows of capital may have been greatly reduced since the expo movement began, but our primary means of expressing our identity is still national. So well has the expo movement sublimated this into an international movement, however, that it has now become an important part of international trade systems. Just as the League of Arab States and the World Water Council have pavilions at the Shanghai Expo, so the Expo itself is part of a network of international organisations into which national governments, for better or worse, speak to each other, resolve disputes and otherwise pursue their national self interest.

The Danish Pavilion features some of the actual material fabric of Copenhagen; seen here, the Little Mermaid statue; photo Iwan Baan

The Danish Pavilion features some of the actual material fabric of Copenhagen; seen here, the Little Mermaid statue; photo Iwan Baan

×Indeed, there is a series of international laws that governs them. The Paris Convention of November 22, 1928, is a legal instrument that regulates the organisation of expos. It established the Bureau International des Expositions, which is based in Paris, a body that has since then updated the convention on different occasions in order to account for the shifts in economic, social and political trends, and, most tellingly, the emergence of new countries. Since Shanghai won the Expo in 2002, China has risen as a global power and expos have received a new lease of life. Countries such as the United States that had ceased to participate in world expos returned to the fold in order to promote business in a massive new market. As a consequence, Shanghai is busier and more competitive than any previous expo.

City bikes, transported from Copenhagen, afford visitors to the Danish Pavilion a somewhat more accelerated tour of the structure; photo Iwan Baan

City bikes, transported from Copenhagen, afford visitors to the Danish Pavilion a somewhat more accelerated tour of the structure; photo Iwan Baan

×Accepting the narrowness of opportunity that this busiest of all expos affords is an important prerequisite to creating a pavilion of interest. The most interesting proposition – not in immediate architectural drama perhaps, but in its reinvention of the symbolic relationship with the nation it represents is the Danish Pavilion, designed by Bjarke Ingels. A simple ramp structure, it offers visitors the opportunity to borrow real Copenhagen city bikes, paddle in clean water taken from Copenhagen's harbour and transported to Shanghai as balast on ships, and as Ingels himself puts it, ‘the ultimate gesture of the real deal, they can see the actual Little Mermaid at the heart of the harbour pool.’ And, indeed, there she sits. Meanwhile, those who visit Copenhagen hoping to see her will instead encounter a sculpture by Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei.

EMBT's Spanish Pavilion at Expo 2010 features a wicker facade over a steel structure

It may seem like a simple sleight of hand, but what Ingels has done is significant – to actually use a sculpture that has come to represent Copenhagen by steady, collective consent, rather than applying his own symbol. To bring a significant element of Denmark’s cultural fabric to the Expo to represent the Danish capital provides a sense of immediacy that circumvents the interpretative process that becomes so wearisome when visiting such an exhibition. As charming as EMBT’s woven Spanish pavilion is, what does it say about Spain? Do the curtains of woven aluminium on the Swiss pavilion successfully convey the theme of rural and urban interaction? Does the spiky British pavilion in fact repel as many visitors as it entices? Even the posing of such questions prevents a direct relationship with the idea.

Korea's pavilion at the Shanghai expo, designed by Seoul-based office Mass Studies; photo Kingkay Architectural Photography

Korea's pavilion at the Shanghai expo, designed by Seoul-based office Mass Studies; photo Kingkay Architectural Photography

×Rather than gaining a true understanding of the material culture of a place you may never visit, you spend most of your time at expos trying to work out how the architect’s design approach reflects a nation. Moreover, the presence of the Little Mermaid isn't trite. Ingels was invited to speak in the Danish parliament to argue why the Danes should hand over a treasured object to the Chinese for six months. He pointed out that the Mermaid and two other fairytales by Hans Christian Andersen are part of the public-school curriculum in China. ‘So all 1.3 billion Chinese actually grew up with her,’ says Ingels. It also makes a virtue of the modesty of Denmark's national monument. Their national monument – unlike Big Ben, say, or the Eiffel Tower – can be easily transported.

Singaporean Pavilion at Shanghai's Expo 2010, designed by Kay Ngee Tan Architects; photo Kingkay Architectural Photography

Singaporean Pavilion at Shanghai's Expo 2010, designed by Kay Ngee Tan Architects; photo Kingkay Architectural Photography

×It was Jude Kelly, Artistic Director of the South Bank in London, who at the Venice Biennale in 2006 elucidated why temporary pavilions were still such an important part of our cultural landscape. She made the following observation: ‘I believe that cultural palaces need to continually dissolve because they’re only containers, and actually it’s the ideas inside, bursting forward, that are most relevant.’ It is the idea and not the design which makes an expo pavilion compelling.