Out on the Tiles: ceramic architectural facades

Text by Dominic Lutyens

London, United Kingdom

23.09.13

Contemporary architects internationally are breathing new life into the old tradition of using ceramic elements on exteriors. The result are striking facades that marry expressive ornament with sustainability.

Ornamental, often textured facades – not seen in significant numbers since the floridly decorative ones on Art Nouveau buildings – have made a comeback in recent years. Architects who have helped spearhead this development include London-based FAT, whose Blue House is fronted by a cartoon-like, powder blue silhouette of a house, and Squire & Partners, which has just completed a house in Mayfair whose facade bristles with 4,000, folded aluminium leaves in bronze. Often bespoke, today’s ornamental facades make a virtue of craftsmanship. And usually made of a single material, they tend to be monolithic yet avoid being dull since they’re unique and eccentric.

One tributary of the trend is a growing number of buildings with large-scale, matt or glossy ceramic facades. These inevitably recall such elaborately decorated Art Nouveau buildings as Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Batlló with its iridescent roof, Paris’s Ceramic Hotel with its glazed earthenware facade, courtesy of ceramicist Alexandre Bigot, and Villa Marie-Mirande in Brussels, which is cloaked with hand-made tiles provided by ceramicist Guillaume Janssens.

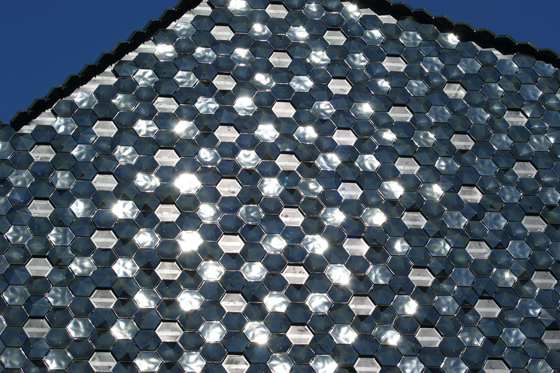

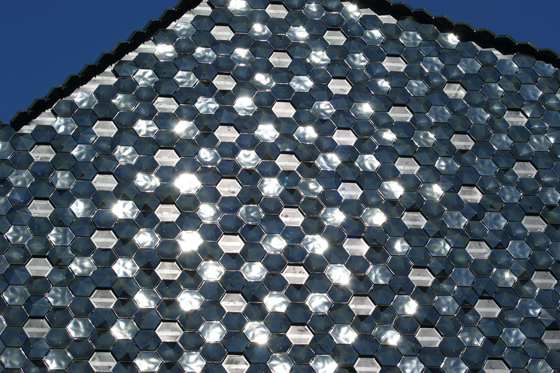

Herzog & de Meuron has added a new roof to Basel’s Museum der Kulturen, whose 3D tiles animate it, especially in strong sunlight. The steeply angled roof deliberately echoes the rooflines of the surrounding medieval buildings

Herzog & de Meuron has added a new roof to Basel’s Museum der Kulturen, whose 3D tiles animate it, especially in strong sunlight. The steeply angled roof deliberately echoes the rooflines of the surrounding medieval buildings

×Centuries older are the dazzling, polychrome mosques of Isfahan in Iran, the earliest dating from around the 8th century. Some believe ceramic facades went out of fashion in the early 20th-century because purist modernist architects were besotted with glass, concrete and steel. However, several mid-century architects who favoured an organic, sculptural aesthetic rediscovered ceramic facades – Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House (1957) and Alvar Aalto’s Seinajoki Town Hall in Finland (1962-65) are both clad in hundreds of tiles.

Today’s architects who create ceramic facades are aware of these traditions. But their versions differ from Art Nouveau buildings in that they marry the potentially decorative quality of ceramic tiles with a contemporary, relatively minimalist aesthetic and boldly sculptural, abstract forms. And architects today often refer to local context. Take Herzog & de Meuron’s renovated Museum der Kulturen in Basel of 2011. Now housing ethnographic artefacts, it was originally designed in 1849 by Melchior Berri, with an extension added by architects Vischer & Söhne in 1917. By the Noughties, it boasted 30,000 objects, and more space was needed. Enter Herzog & de Meuron, which crowned it with a new, double-height gallery floor whose cantilevered roof is clad in a striking, virtually windowless carapace of hexagonal, ceramic tiles in a stormy grey colour reminiscent of the inside of mussel shells. Its convex, concave and flat tiles – supplied by German architectural ceramics specialist Agrob Buchtal – create a 3D surface, and so enhance the sculptural quality of the roof. The tiles also animate the roof’s surface when they sparkle in sunlight. What’s more, the roof’s jagged, asymmetric silhouette evokes a Gothic fairytale but its form isn’t arbitrary or merely fanciful: it’s designed to echo the roofs of the surrounding medieval buildings.

Manuel Herz’s arrestingly jagged Jewish Community Centre in Mainz, Germany is clad in glazed, bottle green ceramic tiles; photos Iwan Baan

Manuel Herz’s arrestingly jagged Jewish Community Centre in Mainz, Germany is clad in glazed, bottle green ceramic tiles; photos Iwan Baan

×The walls of the centre’s interior are covered in densely packed Hebrew letters; photo Iwan Baan

Ceramic tiles form a similarly homogeneous skin around Basel-based Manuel Herz Architects’ Jewish Community Centre in Mainz, Germany, which incorporates a synagogue. In medieval times, Mainz had considerable intellectual influence on European Judaism, though the city’s Jewish community has also been severely persecuted; in 1938, the Nazis destroyed its synagogue. In recent decades, the Jewish population has grown, necessitating new facilities.

Clad in bottle green ceramic tiles, the Jewish Community Centre’s wildly angular form ‘traces in a very abstracted way the Hebrew word “Q’dushah”, which means making sacred,’ says its architect Manuel Herz. The centre’s uniform, apparently hermetic skin might seem forbidding but Herz’s aim was to make the building ‘approachable’ – hence the large public square in front of it. As for the cladding, Herz says, ‘There’s no symbolism to it, it’s just an amazing material which plays extremely well with light.’

The white faience facade fronting One Eagle Place, in London’s Piccadilly, is adorned with a jazzy ceramic cornice by artist Richard Deacon and red window reveals; photos Dirk Lindner

The white faience facade fronting One Eagle Place, in London’s Piccadilly, is adorned with a jazzy ceramic cornice by artist Richard Deacon and red window reveals; photos Dirk Lindner

×One Eagle Place’s interior overlooks Piccadilly’s flickering LED signs. The idea is that the latter are reflected on the building’s white faience facade; photo Dirk Lindner

One Eagle Place’s interior overlooks Piccadilly’s flickering LED signs. The idea is that the latter are reflected on the building’s white faience facade; photo Dirk Lindner

×One Eagle Place, a new project in Piccadilly, London – which involved the refurbishment of old buildings and construction of a new facade made mainly of white faience blocks (glazed earthenware) – is closer in spirit to the sensual style of Art Nouveau architecture. Designed by Eric Parry Architects, its facade features an idiosyncratic cornice created by Turner Prize-winning artist Richard Deacon, whose colourful, abstract patterns were created with ceramic transfers or decals normally used to decorate plates (sourced in Stoke-on-Trent, the UK’s ceramics centre).

The gleaming facade and Deacon’s jazzy patterns are intended to reflect the ‘polychromy and artifice of Piccadilly Circus’. ‘My knowledge of Iranian, Art Nouveau and Vienna Secessionist architecture was bubbling in the background,’ says Eric Parry. ‘But more importantly, I’m against the shallow epidermis of much contemporary architecture. Ceramic facades have depth, they’re voluptuous.’ He also describes them as ‘haptic’ (meaning tactile).

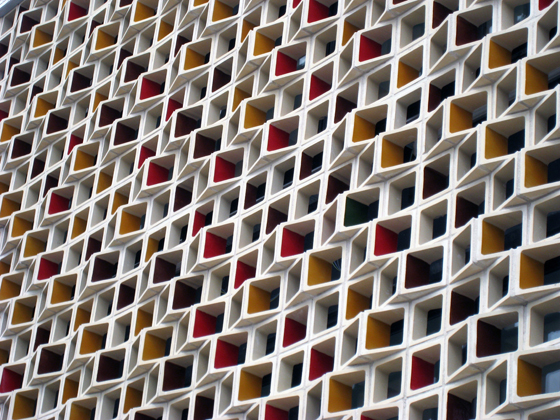

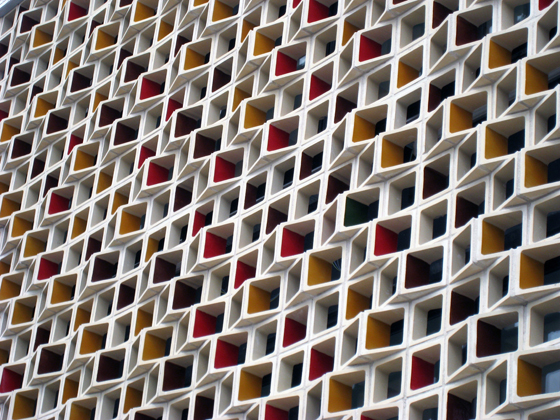

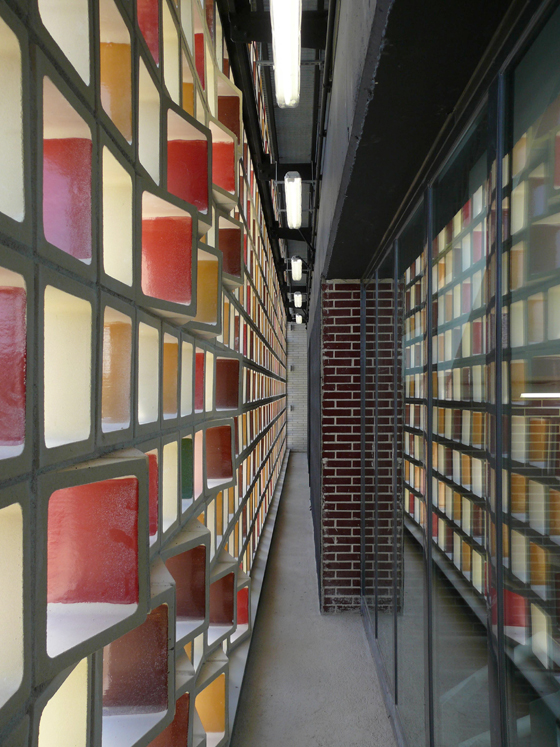

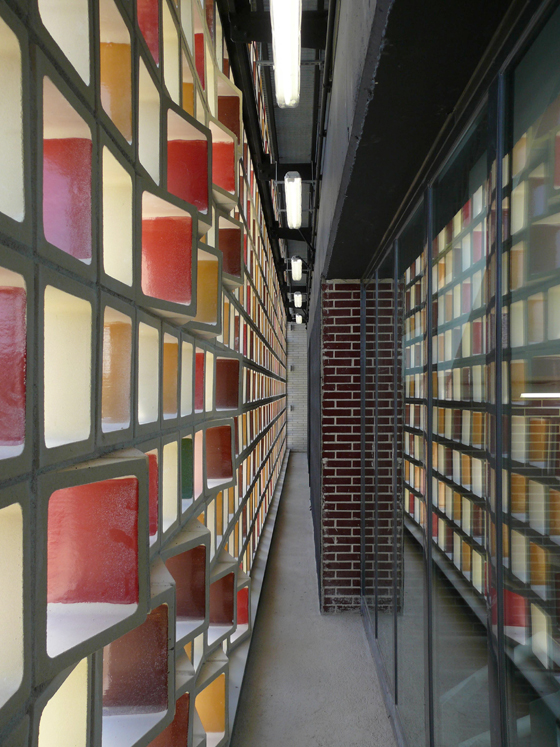

Spanish practice Mestura Arquitectes’ CEIP primary school near Barcelona is fronted by a double skin of ceramic components forming a lattice, supplied by veteran ceramicist Toni Cumella

Spanish practice Mestura Arquitectes’ CEIP primary school near Barcelona is fronted by a double skin of ceramic components forming a lattice, supplied by veteran ceramicist Toni Cumella

×A passion for ceramics and craftsmanship is central to the workshop of Toni Cumella, a ceramicist who, between 1989 and 1992, helped restore Gaudi’s Casa Battló and Parc Güell. Called Ceràmica Cumella and based near Barcelona, the workshop has also collaborated on many cutting-edge architectural projects, notably architects Enric Miralles and Benedetta Tagliabue’s spectacular Santa Caterina food market of 2005 whose undulating roof is carpeted with 325,000 tiles. And Cumella has provided the ceramic lattice on two walls enveloping the CEIP primary school at Cornellà de Llobregat, near Barcelona, of 2010, designed by Mestura Arquitectes. Its ceramic components have angular facets, which, facing one direction, are coated with a warm, red glaze and, facing the opposite way, with a cool, green glaze – and provide a glass box encasing the building’s interior with shade.

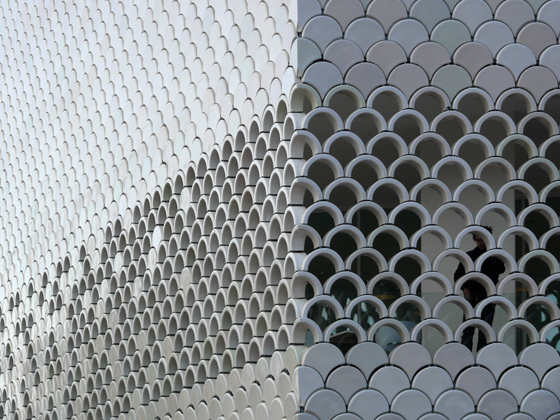

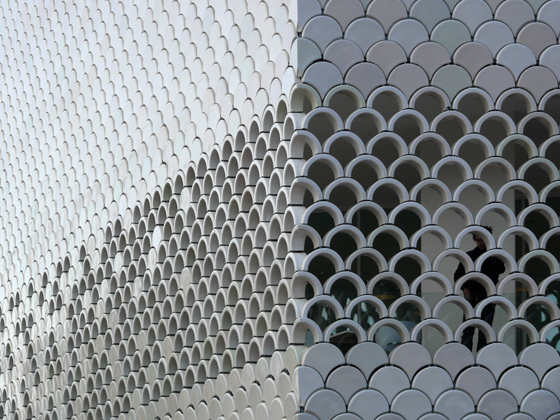

Tiles in seven, subtle shades of white, also provided by Toni Cumella, clad a building designed by architect Pedro Campos Costa – a new addition to the existing Lisbon Oceanarium

Tiles in seven, subtle shades of white, also provided by Toni Cumella, clad a building designed by architect Pedro Campos Costa – a new addition to the existing Lisbon Oceanarium

×A more unusual application of ceramic elements can be found at Spain’s Ushuaïa Ibiza hotel. This features a snaking ceramic wall designed to soundproof the hotel’s restaurant, which adjoins its open-air nightclub. Fashioned out of ready-made elements – ceramic wine racks – the wall doubles as a vertical garden studded with indigenous succulents. According to its creator, Urbanarbolismo, which says the ceramic structure nods to the flowerpots of Andalucia’s patios, the wall is low-maintenance and sustainable since its plants thrive in little soil, withstand strong heat and need only be watered once a month in winter and once a week in summer.

Designed by Spanish architects-cum-landscape architects Urbanarbolismo, this ceramic wall, which doubles as a vertical garden, soundproofs a restaurant in Ushuaïa Ibiza Beach hotel from its adjacent, open-air nightclub

Designed by Spanish architects-cum-landscape architects Urbanarbolismo, this ceramic wall, which doubles as a vertical garden, soundproofs a restaurant in Ushuaïa Ibiza Beach hotel from its adjacent, open-air nightclub

×Indeed, ceramic cladding also appeals for being sustainable. Spanish ceramic tile manufacturers, for example, now recycle many waste products and so use less raw materials, such as water and clay. And these days, single-firing ceramics (more environmentally friendly than double-firing them) is more common.

The resulting products might be decorative but there’s nothing superficial about ceramics used to front buildings. If it’s one thing they’re not, it’s just a facade.