Piling Them High

Text by Dominic Lutyens

London, United Kingdom

19.08.14

Bricks in contemporary architecture may well be saddled with a reputation for retrograde traditionalism – after all, the oldest discovered bricks date from before 7500 BC. For some, they conjure up images of architecturally unimaginative housing estates, but today, many forward-looking architects can’t get enough of the humble brick.

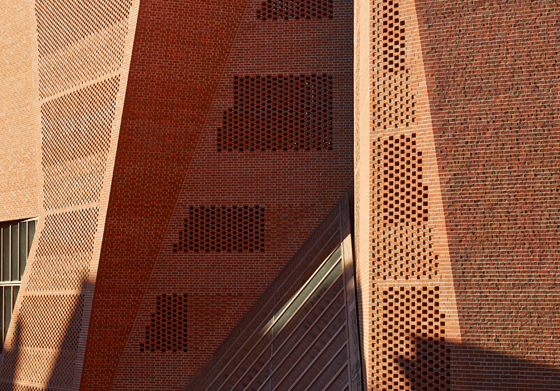

The Saw Swee Hock Student Centre, the London School of Economics’ students’ union, demonstrates the flexibility of bricks, here in a Flemish bond pattern, which can create opaque or transparent structures; photo: Dennis Gilbert/VIEWpictures.co.uk

The Saw Swee Hock Student Centre, the London School of Economics’ students’ union, demonstrates the flexibility of bricks, here in a Flemish bond pattern, which can create opaque or transparent structures; photo: Dennis Gilbert/VIEWpictures.co.uk

×True, modernist architects who wanted their buildings to be light-filled often eschewed the use of fired bricks because of their opacity or unwelcome associations with the past – think Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet’s 1932 Maison de Verre in Paris, constructed from glass blocks.

Not that all modernists felt this way. It’s perhaps not surprising that Alvar Aalto, who pioneered a more organic take on modernism, tested out the aesthetic possibilities of brickwork at his 1953 Muuratsalo Experimental House in Finland. Wishing to marry the building’s aesthetic to its ruggedly natural surroundings, Aalto finished the walls with a multitude of free-form brick patterns. Another mid-century modernist, Uruguayan engineer and architect Eladio Dieste, is known for his wide-span Gaussian vaults – slender yet strong structures supporting roofs made of one layer of brickwork. And Louis Kahn’s use of local brick and concrete in his design for the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, India (begun in 1962) nods to the country’s vernacular architecture yet looks modernist in its simplicity. Gargantuan openings in its facade provide natural ventilation that offsets the bricks’ thermal mass.

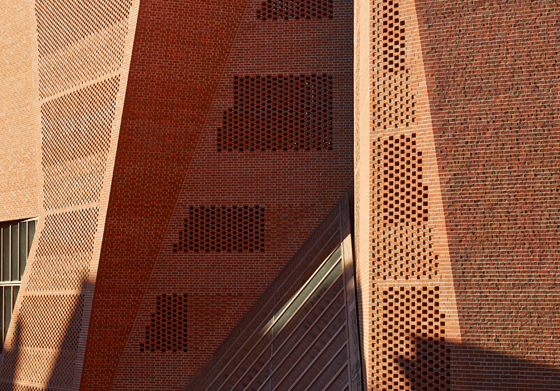

The perforated parts of the facade of the LSE’s students’ union allow daylight to enter it — and give it a slightly Moorish feel; photo: Dennis Gilbert/VIEWpictures.co.uk

The perforated parts of the facade of the LSE’s students’ union allow daylight to enter it — and give it a slightly Moorish feel; photo: Dennis Gilbert/VIEWpictures.co.uk

×Since the start of his collaboration with Helga Timmermann in 1984, German architect Hans Kollhoff has used bricks to create buildings in a classical style. His high-rise Kollhoff Tower on Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz, which recalls an American Art Deco skyscraper, is made of peat-fired, rust-red bricks, almost in defiance of the comparatively high-tech structures of Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers nearby. However, Kollhoff’s classical approach has received brickbats for appearing retrograde. Caruso St John’s more recent Brick House in London – with its homogeneous, internal skin of elegantly pale yellow, fair-faced (unplastered) brickwork – was nominated for the Stirling Prize in 2006, a sign perhaps that brick was finally being reappraised.

Today, architects increasingly recognise that bricks have positive attributes. A new-build in an area where brick buildings already exist acknowledges its context. And, as compact, modular building blocks, bricks offer limitless flexibility to architects who want to create idiosyncratically sculptural, textured or patterned buildings. (In fact, it’s possible to be quite nerdy about fired-bricks alone that come with their own extensive glossary of terms denoting shapes, dimensions, colours, types of perforation and indentation, as well as words to describe how they are cut or glazed and their resistance to such things as chemicals or heat.)

The semi-transparent facade of the ABC Building in Seoul reveals the position of the staircase — fronted by solid brickwork — behind it. Views of a local park can be glimpsed through the perforated wall alongside the staircase (above)

The semi-transparent facade of the ABC Building in Seoul reveals the position of the staircase — fronted by solid brickwork — behind it. Views of a local park can be glimpsed through the perforated wall alongside the staircase (above)

×Bricks are also durable – and sustainable, given that they’re composed mainly of organic materials. Inspired perhaps by a Moorish approach, architects are even challenging the perception of brick structures as opaque and leaden by perforating brick walls to let more light and air into buildings or to create decorative patterns.

One highly sophisticated, recent use of brick can be seen at O’Donnell + Tuomey’s Saw Swee Hock Student Centre, the London School of Economics’ swanky students’ union – complete with gym and cafés – whose red-brick walls shoot off at dramatic angles. Its unorthodox shape was determined by the web of medieval lanes around its site, which imposed restrictions based on sight lines and neighbours’ rights to light. ‘Our design relates to the resilient character of the city’s architecture with familiar materials made strange,’ says Sheila O’Donnell. ‘The bricks on the external walls are used in a new way with an openwork pattern that creates dappled light inside; at night, when the lights are on inside, the building seen from the street looks like a glowing lattice lantern.’ Despite its arresting form, the architects’ aim was to design a building that blends as seamlessly as possible with the surrounding streets, thanks to its use of brick and partially porous facade.

Joho Architecture deployed bricks to create the sculptural, organic form of its Curving House in South Korea. The architects compare it to the shape of a fish

Joho Architecture deployed bricks to create the sculptural, organic form of its Curving House in South Korea. The architects compare it to the shape of a fish

×Designed to resemble fish scales, angled bricks combined with polished stainless steel on the textured facade of the Curving House create a simultaneously mirrored and matt finish

Designed to resemble fish scales, angled bricks combined with polished stainless steel on the textured facade of the Curving House create a simultaneously mirrored and matt finish

×An openwork brick wall on the facade of the ABC Building in Gangnam, Seoul, designed by Wise Architecture, also promotes the idea that brickwork can be transparent. Fronting a staircase leading up the house, this affords those climbing it stunning, if tantalisingly veiled, vistas of a local park. Unusually, this is a dry-brick wall – no mortar was used to fabricate the masonry.

Bricks create an intriguing texture reminiscent of fish scales on the facade of another South Korean project, The Curving House by Joho Architecture. Ash-coloured bricks at different angles are teamed with polished stainless steel, a combination that plays optical tricks: while the bricks cast graphic shadows, the mirrored steel surface reflects the rural surroundings and seems to disappear.

Meanwhile, when Munich-based architect Dominikus Stark deployed handmade bricks as the main material for his pleasingly minimalist Nyanza Education Centre in Rwanda, his aim was to reference local building traditions and pay tribute to the craftsmanship that lies behind the bricks’ production. In the same spirit, its wicker doors were made by local basket-makers.

A concern for sustainability inspired HMA Architects & Designers to recycle and reconfigure the bricks of a former factory to create a new exhibition centre for Shanghai’s World Expo 2010

A concern for sustainability inspired HMA Architects & Designers to recycle and reconfigure the bricks of a former factory to create a new exhibition centre for Shanghai’s World Expo 2010

×For HMA Architects & Designers, who converted a former factory into a pavilion for Shanghai’s World Expo 2010 in the city’s historic Puxi district, sustainability was also a key consideration, although not to the exclusion of aesthetics. The project saw them tear down parts of the factory that were structurally unsound, then reuse the bricks to create walls with intricate, decorative patterns.

In fact, architects often use bricks to suggest a link between past and present. For example, when architects Inger and Johannes Exner restored the fire-ravaged, 13th-century castle Koldinghus in Jutland, Denmark, a project completed in 1992, parts of the original walls were conspicuously covered with new bricks to highlight the fact that the building is constantly evolving. And Pritzker Prize-winning Chinese architect Wang Shu – a keen advocate of architectural heritage who teaches bricklaying skills to his students at the China Academy of Art – constructed the facade of his 2008 Ningbo Museum using recycled bricks.

Chris Dyson Architects’ recently built extension to a Georgian terraced house in London is designed to blend as authentically as possible with the surrounding architecture, thanks to its use of soot-washed bricks and traditional bricklaying

Chris Dyson Architects’ recently built extension to a Georgian terraced house in London is designed to blend as authentically as possible with the surrounding architecture, thanks to its use of soot-washed bricks and traditional bricklaying

×History is also alluded to in British artist Alex Chinneck’s surreal installation in Margate called ‘From the Knees of My Nose to the Belly of My Toes’ – a derelict house whose facade has been replaced with a new, curving, brick frontage that looks as though it has slipped down, in the process exposing a cross-section of the dilapidated top floor. Chinneck sees it in the context of the current regeneration of Margate, and since the installation is in a formerly affluent area, it appears to be an elegiac comment on urban decay and faded grandeur.

Alex Chinneck approached companies to donate materials and manufacturing techniques to create this installation in Margate in the UK. Sponsors and supporters included British brick manufacturer Ibstock Brick

Alex Chinneck approached companies to donate materials and manufacturing techniques to create this installation in Margate in the UK. Sponsors and supporters included British brick manufacturer Ibstock Brick

×As for the shape of bricks to come, digital tools that allow designers to create increasingly complex geometries are now being applied to cutting-edge, automated bricklaying techniques. Swiss architects Gramazio & Kohler are at the forefront of this development. Their transportable ROB robot, which can easily be brought on-site, speedily and accurately constructs brick walls featuring curves and patterns of astounding complexity. So far, this technology has been used to construct such projects as the Gantenbein Winery in Fläsch, Switzerland (in collaboration with architects Bearth & Deplazes) and the extravagantly curved brick wall, Structural Oscillations, showcased at the Venice Biennale in 2008.

Far from being a stick-in-the-mud material, the archetypal brick looks set to excite architects for the foreseeable future.