London

Text by Klaus Leuschel

Bern, Switzerland

19.08.14

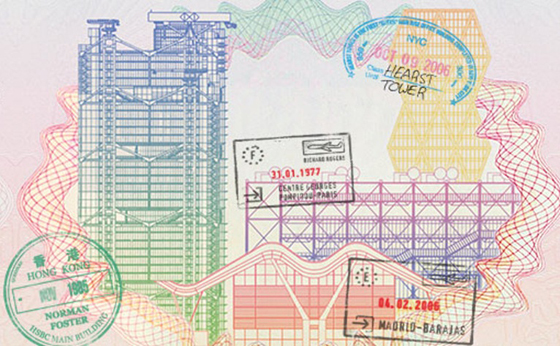

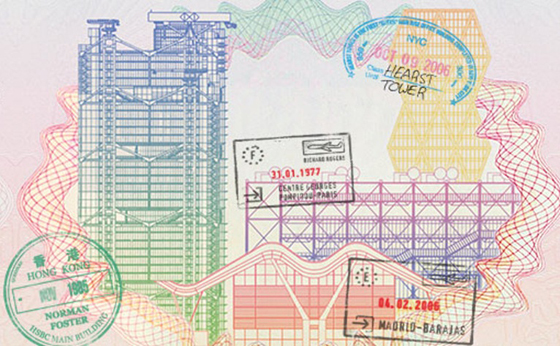

‘The people did not like St Paul’s. They were against the Eiffel Tower. They liked neither the Sydney Opera House nor the Centre Pompidou. But today, millions of photos of these buildings are sent around the world via e-mail and by phone.’ (Jan Kaplicky, Future Systems)

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) opened its renovated gallery with ‘The Brits who Built the Modern World’ (exhibition poster)

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) opened its renovated gallery with ‘The Brits who Built the Modern World’ (exhibition poster)

×London is not only the capital of Great Britain, it’s also the largest city in Europe and one of the strongest economical powerhouses worldwide, attracting more than 30 million visitors annually (2008). Many of them no doubt visit Tate Modern (Herzog & de Meuron) – some probably by crossing the Thames via the Millennium Bridge (Foster + Partners). Considering all the first-class tourist attractions it has to offer, one wonders if visitors will remember London as a future-oriented city, or if most of them identify it primarily with the glory days of a bygone empire – with Queen Victoria and Victorian buildings, or Harrods and Selfridges. They may, with some irony, reach the conclusion that while they’re grateful for the wonderful time they’ve had thanks to intelligent and long-term investments made in architecture 150 years ago, it remains to be seen, when looking at some of the newer buildings, whether their grandchildren will still want to visit London.

Parallel to the exhibition, the BBC featured – as part of its ‘Nation Builders’ series – a three-part documentary of exceptional quality called ‘The Brits who Built the Modern World’ (180 min.)

When broadcasting ‘The Brits who Built the Modern World’ in February of this year, the BBC’s intention may have been to distract rather than to focus. By showing the excellence of five architectural practices in London – Farrells; Foster + Partners; Grimshaw; Hopkins; Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners – whose origins are closely linked to what has been labelled high-tech (originally, Terry Farrell was Nicholas Grimshaw’s partner), the message of the programme was: Fly to Paris if you wish to experience a cultural centre for the 21st century (Centre Pompidou: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers) or to Hong Kong for one of the most intelligently designed skyscrapers (HSBC: Foster + Partners). Enjoy Cornwall if what springs to mind is the rainforest, ecology and sustainability (Eden Project: Grimshaw), or Berlin (Reichstag: Foster + Partners), or perhaps the Senedd in Cardiff (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners) if you want to see outstanding buildings commissioned by the government. But London?

London’s 20th-century modernist tradition is one of the city’s hidden treasures. Whether it’s the Penguin Pool at London Zoo (Lubetkin / TECTON), the Isokon building or 10 Palace Gate (Wells Coates) or the last of the remaining Joseph boutiques / restaurants (Eva Jiricna) – they’re all jewels, not immediately apparent to visitors, yet known to the cognoscenti.

London has the highest density of first-class architectural practices worldwide. So whether architects are building for Lloyd’s (Rogers), Swiss Re (Foster), Rothschild (Koolhaas) or the London Olympics (Zaha Hadid, Michael Hopkins), the city is guaranteed first-class architecture. But there are exceptions, such as the Docklands project and the chaos that was part of its redevelopment.

If it’s a ‘gherkin’ (in the background), then the building in the foreground looks like a ‘cheesegrater’ – even if Richard Rogers does not like the term: The Leadenhall Building (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners)

If it’s a ‘gherkin’ (in the background), then the building in the foreground looks like a ‘cheesegrater’ – even if Richard Rogers does not like the term: The Leadenhall Building (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners)

×Nowadays everything seems to be about success and export. The banks, the economy and the government all love success stories, which is why they enjoy reading that an estimated 75 per cent (possibly even 90 per cent) of the work coming out of these architectural practices is built worldwide, demonstrating that the benchmarks are set in London. When politicians praise the work of architects, we should remember that there are perhaps 20,000 people in London working in those architectural studios, and for engineers and other specialists, such as model builders. There’s little evidence, however, that those making the decisions actually prefer a particular style or practice – Ken Livingstone being the exception that proves the rule in that Richard Rogers was his architectural and urbanistic consultant of choice.

One of the landmark buildings for the 2012 London Olympics was the Velodrome (Hopkins Architects), photograph: Nathaniel Moore

One of the landmark buildings for the 2012 London Olympics was the Velodrome (Hopkins Architects), photograph: Nathaniel Moore

×While Vanbrugh, Hawskmoor and Wren profited in their day from direct patronage (be it from noblemen or the established church), the majority of patrons today are real estate companies or property funds – for the most part anonymous. With nothing to indicate that the decision makers in these companies have any criteria (other than money) for evaluating architectural qualities, there’s little hope for the future. It’s worth noting that a Gherkin (Foster + Partners), a Shard (Renzo Piano Building Workshop) and a Cheesegrater (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners) acquire a media presence because they stand out from the hotchpotch that is otherwise built. This may provide the yardstick we need in order to differentiate between building and architecture, and maybe attractive workplaces will help to convince some people (banksters and insurance gangsters) that better buildings have more to offer the public than merely beautiful facades.

According to various sources, London has for years been short of approximately 125,000 housing units, which are needed to relieve pressure on ‘the single most globalised city’ (McKinsey, 2007). ‘As with Paris and Art Nouveau, and for that matter New York with jazz, London’s core strength is its role as diffusion centre and meeting place. Ideas and inventions may happen anywhere, but they come to London to reach the world. This is London’s greatest asset and, history has shown, its most enduring.’ These words are taken from a report (‘London – A Cultural Audit’, London Development Agency, 2008) commissioned by Ken Livingstone, who was mayor of London at the time. The report concludes that, as a consequence, London’s cultural offerings should never be taken for granted. Is that because the mayor was aware of the fragile state of the private sector? He must have known that there was nothing in the public realm to balance the risks involved.

The Orbit – conceived by Anish Kapoor in cooperation with the engineer Cecil Balmond (Arup AGU); photographs: © 2014 Anish Kapoor

The Orbit – conceived by Anish Kapoor in cooperation with the engineer Cecil Balmond (Arup AGU); photographs: © 2014 Anish Kapoor

×There’s no simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ when it comes to asking if London gets the buildings it deserves. Visitors are quite likely to respond with a ‘yes’, whereas those who spend hours commuting back and forth to their jobs in the city would arguably say ‘no’. To use a football analogy, London is to architecture what the Premier League is to the worldwide sport: the most attractive league with an awful lot of money being poured into its clubs. On the other hand, rocketing ticket prices must remain affordable to the spectators packing the stadiums, who, historically, were from the working classes. In that sense, today’s huge crowds also represent a shift in marketing: targeting higher-income earners seems to have been the perfect solution.

In 2014, London can offer visitors a Gherkin, a Shard and a Cheesegrater. It has an Aquatics Centre (Zaha Hadid) and a Velodrome (Michael Hopkins) and – as if marking a trip to London by King Kong – the ArcelorMittal Orbit (Anish Kapoor), which looks as though the giant ape has reworked a roller coaster into a kind of recycled sculpture. In addition to famous tourist attractions like Tate Modern, London also offers the best offices, strengthening its position as ‘the world’s top business centre’ (Ken Livingstone). What it doesn’t offer, though, is an answer to the question of how to balance centrifugal forces linked with globalization (tourism, top jobs, luxury apartments) – that is to say, how to respond to the loss of workplaces when, in industrialised countries at least, only two-thirds of the working population will be able to find jobs.

Contemporary (housing) architecture? A rare example – 217 residential units by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners: NEO Bankside; photographs: Edmund Sumner/RSHP

Contemporary (housing) architecture? A rare example – 217 residential units by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners: NEO Bankside; photographs: Edmund Sumner/RSHP

×Centuries ago, Shakespeare wrote of Venice, Verona, Rome and Athens as if they were neighbouring villages. This same spirit still dominates the average Londoner’s image of the common dream-house: ‘Semi-detached, Suburban’, as Manfred Mann once sang. The reality is different in the sense that the situation now demands much more intelligent forms of ‘congestion’, to quote Rem Koolhaas, or Richard Rogers, who argues in ‘Cities for a Small Country’ that we will be forced to live more compactly in order to waste less. So while the popularity today of once critically perceived buildings like the Balfron Tower, the Barbican or Bevin Court may be a sign of changing perceptions, they are now far too exclusive for the low-cost living that’s required. Nevertheless it would be unfair to blame architects wholesale for a shortfall that obviously has its origins in economical, political and social preferences.

What is certain is that some of those ‘Brits who Built the Modern World’ (Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, Homeshell/Insulshell and Y:Cube) even came up with proposals that had no actual clients, or tried new ways on their own (Grimshaw: Park Road Apartment Building; Foster: Riverside Apartments).

PS Strictly speaking, the opening quotation from Jan Kaplicky is not entirely correct. When he wrote down his thoughts, photos were not yet being sent via computer or phones. Those were the glorious days when people still sent postcards.

---