Sounding Out: room acoustics make themselves heard

Text by Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Switzerland

28.05.13

When was the last time a building won an award for the way it sounds? Architecture, and by extension society, has long privileged the visual over the aural. Yet a number of architects are starting to think and design in a more complete sensory way, informed by the research of acoustics experts. Listen up.

Felt makes its presence felt at interior architects i29’s interior for marketing agency Tribal DDB Amsterdam, where the sound-absorbing material is applied to structural elements as well as furniture and lighting

Felt makes its presence felt at interior architects i29’s interior for marketing agency Tribal DDB Amsterdam, where the sound-absorbing material is applied to structural elements as well as furniture and lighting

×In the arsenal of recently coined terms to vilify the various manifestations of what we have come to call antisocial behaviour, there’s a new word on the block: sodcasting.* This neat bit of wordplay, which in Britain is rapidly gaining currency to describe the act of playing loud music on a mobile phone in a public space, usually on public transport, exemplifies what sound expert Julian Treasure describes as ‘the paradigm of personal broadcasting that we have all fallen into’.

Author of the book ‘Sound Business’ and chairman of the UK-based Sound Agency, Treasure considers us all guilty, to a greater of lesser extent, of making this world an ever noisier one. While technology, with its beeps, whirrs and general signs of electronic life, has served to turn up the overall volume dial, certain aspects of technology cause us to behave badly ourselves. A prime example of this is mobile telephony, which has in a relatively short space of time displaced a shared, centuries-old understanding of such notions as consideration and privacy.

Designer and Head of Programme at the Royal College of Art Ab Rogers has delivered an acoustically optimal restaurant interior for PizzaExpress in Richmond, London. 'Living Lab' allows guests to conduct conversations with ease, even when the space is full

Designer and Head of Programme at the Royal College of Art Ab Rogers has delivered an acoustically optimal restaurant interior for PizzaExpress in Richmond, London. 'Living Lab' allows guests to conduct conversations with ease, even when the space is full

×For Switzerland’s leading acoustics specialist Sergio Baumann, the human voice is the number-one contributor, in contemporary service-based, non-manufacturing economies, to the presence of noise in the workplace. As machines have got – for the most part – quieter, talking-generated sound levels in offices have burgeoned. Baumann, who heads up the Zurich-based renz solutions, a consultancy specialising in the design and delivery of acoustics, lighting and climate systems to end clients and investors, argues that the majority of acoustics products on the market don’t address this, having been created to absorb medium and high-frequency sound. A broader band approach is needed. Baumann, who, talking passionately about his work, is himself anything but antisocial, puts it simply: ‘Man likes to be with other people, but doesn’t like to be disturbed.’

By Baumann’s own admission, his company ‘are not the friends of architects’, more often than not being invited to enter the build process once the architect’s plans have been agreed. ‘We point out what acoustics-wise isn’t working,’ he explains. ‘A lot of architects don’t want to hear this.’ (No pun intended.) Julian Treasure attributes – to mix the senses – this short-sightedness on the part of many architects to things aural to the little time spent, while training, on the issue of sound. ‘There is a very strong association,’ he says, ‘of the word “design” with the visual. And societally, we have a strong tendency to prioritise the eyes.’ The result of such a sensory hierarchy is, in architectural terms, the creation of spaces which aren’t fit for purpose, argues Treasure. ‘Most of the rooms we exist in are an accidental by-product of the way they look,’ he says.

Portuguese practice CVDB Arquitectos's Braamcamp Freire Secondary School in Lisbon corrects the historic underperformance of school buildings in terms of acoustics with visually striking sound-absorbing panelling in classrooms, corridors and the main hall

Portuguese practice CVDB Arquitectos's Braamcamp Freire Secondary School in Lisbon corrects the historic underperformance of school buildings in terms of acoustics with visually striking sound-absorbing panelling in classrooms, corridors and the main hall

×Take school buildings. Baumann, whose research underscores the fact that higher levels of background noise effect a dramatic decrease in the ability of students to engage fully in classroom-teaching ¬– and, indeed, to answer questions correctly – uses sophisticated modelling software to show how sound levels ‘spiral’ upwards the harder we all try to make ourselves heard in noisy environments. Noise begets noise. Mapping the way sound behaves in a space, however, provides the client with a roadmap for acoustic optimisation – one based on material and structural interventions, as well as internal reconfigurations – whose effects can be clearly measured.

The poor acoustic performance of school environments is a bête-noire of Treasure’s, too. ‘We invest all this money and time in teaching and the syllabus,’ he explains, ‘but it’s all about sending. There is no conversation about receiving. That’s insane. The building is part of the process of communicating.’ Ab Rogers, the London-based but internationally practicing designer, who is also Head of Programme for Interior Design at the Royal College of Art, agrees. ‘We need to be creating for all five senses and beyond in this day and age,’ he maintains. ‘Interior design is not just an aesthetic thing. It’s very much about the performance and the programme of space. Clients and participants have higher expectations of their surroundings these days and that leads to the want of greater sound improvement.’

CNC technology is behind the acoustics-enhancing, undulating cut timber that lines the Cave Restaurant in Sydney, designed by Koichi Takada Architects

CNC technology is behind the acoustics-enhancing, undulating cut timber that lines the Cave Restaurant in Sydney, designed by Koichi Takada Architects

×Rogers should know. He’s delivered a number of successful projects that place just as much value on the design of acoustics as they do on their scopic function. His ‘Living Lab’ in Richmond, London, for UK restaurant chain PizzaExpress consciously sets out to create an environment that optimises the way sound works for its guests, reducing the effort required to speak and to hear fellow diners, while allowing them to enjoy the activity of a busy public space. A quasi-privacy is created by the installation of acoustic domes over dining booths, with the introduction of iPod docks within the booths and suspended circular acoustic panels throughout restaurant completing the soundscape. The results stand up to empirical scrutiny. A BBC television programme put Rogers’ scheme to the test, identifying a 50% reduction in unwanted noise compared to the previous fit-out.

Rogers isn’t alone. An increasing number of architects are heeding the clarion call by acousticians and sound experts to design with their ears as much as with their eyes, to create, as Treasure puts it, ‘experiential architecture – a designed experience, not just appearance’. If schools rank among the worst offenders for poor sound performance, Portuguese practice CVDB Arquitectos’s Braamcamp Freire Secondary School in Lisbon attempts to correct this with its numerous acoustic measures. While classrooms feature yellow, acoustically panelled ceilings, circulation spaces are lined with special concrete, sound-absorbing blocks. The sound-optimised main hall, meanwhile, is clad with timber studs and acoustic panels.

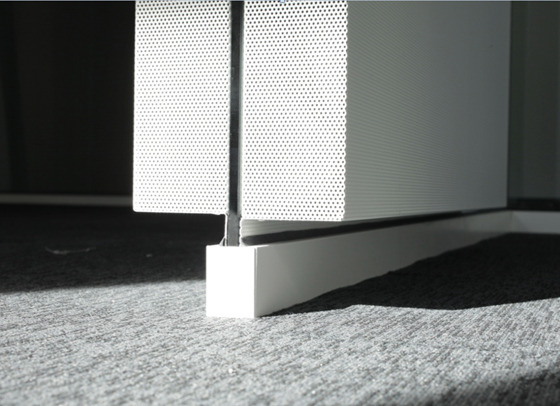

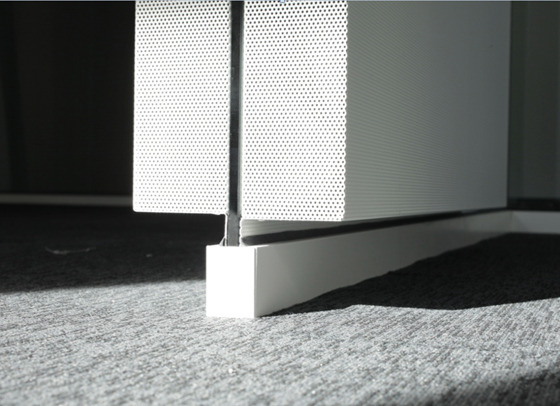

Detail from a project delivered by Swiss acoustics experts renz solutions, where glass lined on both sides with a layer of sound-absorbing material is used to divide and acoustically manage open-plan space

Detail from a project delivered by Swiss acoustics experts renz solutions, where glass lined on both sides with a layer of sound-absorbing material is used to divide and acoustically manage open-plan space

×Hospitals, too, serially underperform in terms of sound management, but again, there are examples of recently completed projects that address the negative impact that noise – in particular from essential machines that are designed to save lives – can have on the recovery of patients. Foster + Partners’ CircleBath hospital in England is one such project. A privately funded initiative, the relatively small facility invests not only in a high level of consideration in terms of spatial organisation and specification of materials, but also in how sound behaves within the building. The double-height atrium, for example, which houses the reception, café and nurses’ station and leads to the private consultation rooms, features suspended natural-wood acoustic panels, interspersed with glass ones.

In the realm of the workplace, meanwhile – where a sobering statistic from Julian Treasure reveals that the sound of unfettered talking in open-plan offices can reduce productivity of others by up to 66% when they are reading or writing – projects such as interior architects i29’s design for digital marketing agency Tribal DDB Amsterdam take noise seriously. To mitigate the rising decibels that an open and flexible workplace, designed for creative interaction, can generate, the Dutch practice developed an acoustic response based on the holistic use of fabric. Durable, fireproof felt, with its excellent sound-absorbing qualities, was applied to the ceiling and walls, as well as to furniture and lighting, creating a unified and welcoming visual scheme with an additional tactile benefit. Soft on the eyes, soft on the ears, and soft to the touch.

Natural-wood acoustic panels, interspersed with glass ones, line the double-height atrium at Foster + Partner's highly considered CircleBath hospital project in England; photos Nigel Young, Foster + Partners

Natural-wood acoustic panels, interspersed with glass ones, line the double-height atrium at Foster + Partner's highly considered CircleBath hospital project in England; photos Nigel Young, Foster + Partners

×If there’s one notable trend in acoustic design, it has to be, for Ab Rogers, that the behaviour of sound is starting to be taken more seriously by more people, beyond specialist spaces like concert halls. The designer welcomes acousticians being brought into projects earlier on in the process, not just as retroactive remedial fixers, resulting in projects ‘that look fantastic and behave accordingly with regard to sound’. Sergio Baumann, who conducts monthly acoustics seminars at renz’s Solutions Center, where clients get the opportunity to ‘feel on their bodies what the difference is between good and bad acoustics’ also sees the sound landscape changing. ‘It’s like a vaccination,’ he says, meaning that once you understand just how important sound is to the experience of space, you can’t go back.

Yet, clearly, there’s still a lot of work to be done to tackle the hierarchy of the senses that so often subjugates the way interiors work on an aural level to an afterthought. Treasure sees training as key. ‘I’d love to see acoustics included in an architect’s training in a much more serious way, with more of a conversation between architects and specialists,’ he says, throwing down the gauntlet. ‘It could be a great new material to play with. How about designing the sound of a space first, then making a building that looks the way it needs to look to make that sound?’

You heard him, people.

....

* ‘Sod’ is a pejorative term used in the United Kingdom for someone who is considered contemptible or obnoxious.