»Cold War Modernism«

Texto por Architonic

Suiza

12.11.08

The collapse of Adolf Hitler's tausendjähriges 'Reich' led to a new world order, with on the one side the USA and NATO, which came into being in 1949, facing their counterpart in the form of the USSR and its alliance of Warsaw Pact states, an alliance which lasted from 1955 to 1991.

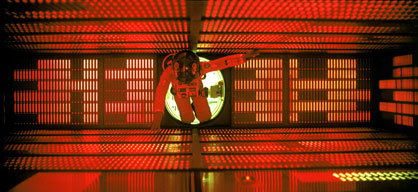

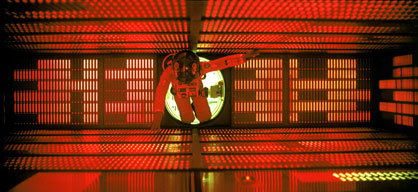

2001: A Space Odyssee (Director: Stanley Kubrik) © V&A London

The collapse of Adolf Hitler's tausendjähriges 'Reich' led to a new world order, with on the one side the USA and NATO, which came into being in 1949, facing their counterpart in the form of the USSR and its alliance of Warsaw Pact states, an alliance which lasted from 1955 to 1991. Black contrasted with white here, with hardly any shade of gray in between.

This bipolar view of the world has its most prominent emblem in the image of the Iron Curtain, as a form of fire protection deriving from the theatre which keeps the undesirable on the outside – which, by the way, was the attitude on the one side of the wall just as much as on the other, almost as if we were dealing with the mirror image of one and the same ideology.

Superman? Supermen! (Robert Ciesilewicz) © ADAGP Paris + V&A London

For the first time a varied and multi-layered range of cultural facets of this black and white vision of the world is now being explored in a groundbreaking exhibition, »cold war modern«, which runs at London's V&A (Victoria & Albert Museum) until 11 January 2009.

Those who assume that what is on display will be at best one-sided will be in for a disappointment, in a positive way. Equally disappointed will be those who believe that in architecture and design this was a period characterised more by »Biedermann« than by »fire raisers«.

In the chronology of events the journey through time stretches from the reconstruction of bombed cities on both sides of the Iron Curtain to contemporary visions of modern life, with the competition between the (better) ideas in East and West reflecting the two worlds just as much as the arms race. The »Interbau« buildings in West Berlin designed by Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer and Richard Neutra make a more modern impression than the Stalinallee in the East of the city. However, in retrospect we would be justified in laconically describing this as an anticipated gable modernity under postmodern influences: »Marx was here!«

Food for thought is also provided by the fact that the »kitchen debate« which took place in 1959 between Nixon and Khrushchev in Moscow on the occasion of the »American National Exhibition« can today be regarded as the spark which led to a lasting transformation in the design of the modern kitchen. As a consequence the dishwasher and the fridge made their entry into the concept of the modular kitchen, and ever since there has been talk of the »Americanisation of the kitchen«, even if this influence in Europe is noticeable mainly with reference to the technology.

Messerschmidt cabin scooter (Design: Fritz Fend 1955) © Neue Sammlung München + V&A London

The Cold War reached its most critical point in the years 1961/62. First the Berlin Wall went up and only one year later the stationing of Russian rackets in Cuba brought the world to the brink of World War III. For the curators of the exhibition what marked this period and has therefore survived it – not least thanks to the media – is the imagination of Ken Adams, a set designer who had a lasting influence on the locations of Stanley Kubrick's film epic »Dr. Strangelove« and those of »Goldfinger«, for example. Lasting? Well, in the former British empire at least, the term »Martini modernism« has, wherever the Queen's English is spoken, established itself as the definitive term for the post-war modern.

The exhibition's curators claim that during a dark political age Bond, or more correctly »James Bond« of course, gave expression to modernism, together with hope and a future. Those who measure this in terms of the condition of design at the time would hardly be able to avoid agreeing with them, in that the work of Dieter Rams (Braun) and Eliott Noyes (IBM) was subject to the ideological compulsion of the best of all possible worlds and was flourishing in a unique way. In this context it is not significant that the exhibition marginalises designers such as George Nelson, Robert Probst (Herman Miller) or Ettore Sottsass (Olivetti). In line with the tradition of art history established in the UK by the originally German-speaking immigrants Ernst Gombrich, Erwin Panovsky and Nikolaus Pevsner, there's room for everything here, even if some aspects are only touched on 'en passant'.

In view of the many and varied influences which shaped the image of the age, two seemingly secondary objects in fact became emblematic for the period, both of them from the divided Germany which had risen from the ruins (East Germany) and the economic miracle (West Germany). In terms of the 'zeitgeist' the Messerschmitt cabin scooter, which was a product of the American Marshall Plan and accordingly also a symbol of the American dream and the »American way of life«, matches the world view of Dr. Strangelove or James Bond.

The other object presented by curators Jane Pawitt and David Crowley as one of the highlights of the exhibition is the »Garden Egg Chair«, a design which contains everything required for a major revival - the design was produced in the capitalist West Germany, but it was marketed in the socialist GDR. It remains the preserve of Sigmund Freud and psychology to see within it the precursor for Achille Castiglioni's »Grillo« telephone and accuse other telephone manufacturers in the future of plagiarism.

Garden Egg Chair (Design: Peter Ghyczy 1968) © V&A London

Student unrest, with their rebellion against the structures whose architectural expression could be described as the second infusion of a rigidified modernism, was not the least of the factors which heralded the end of the Cold War in Europe. With the exception of Florence this moment is nowhere more visible than in London, where there was an intense debate going on about the redirection of developments in architecture. Peter Cook created »Archigram« there and at the »Architectural Association« the revolution in architecture was promoted from »Haus Rucker & Co« to »COOP Himmelb(l)au« and expressed in poetry. And former fellow travellers suddenly came to a parting of the ways: above all Alison and Peter Smithson on the one hand, James Gowan and James Stirling on the other.

Decisive at the time was the intervention of »the one and only« Reyner Banham, the incomparable architectural historian and critic (student of Sir Nikolaus Pevsner), who identified the potential of the future in Stirling's struggles to achieve a technicist formal idiom. It was also this alliance which provided architecture with a lasting stimulus. With Archigram, Norman Foster, Nicolas Grimshaw, Michael Hopkins, Jan Kaplicky, Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers and others a movement came into being which, as »high tech«, caused a sensation. And which Banham would later describe as »a style that almost was«. With which the dogma of modernism finally gave way to the pluralist stylistic debate which, as postmodernism, marks a new epoch.

Jested TV tower Liberec; Arch.: Karel Hubáček (Czech Republic, 1968 – 73) © V&A