'Form follows fear': in conversation with Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt

Texto por David Sokol

Washington, DC, Estados Unidos

28.04.10

Architonic talks to Miami-based artists Roberto Behar and Rosario Marquardt about the relation between art and architecture, and how public space has become more contested than ever.

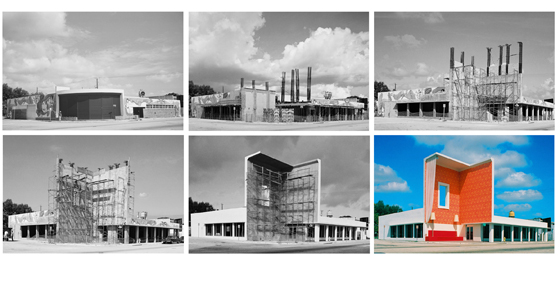

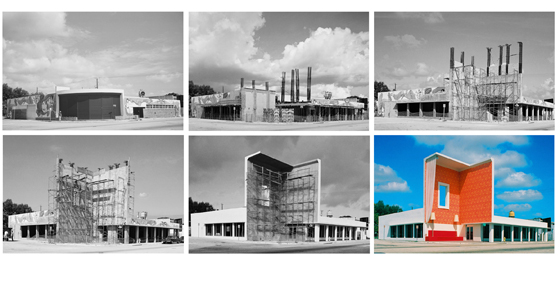

Long before architects were commissioned to sign their names on skylines across the globe, artists were largely responsible for creating local icons. And few of those public artworks have achieved the notoriety of 'The Living Room'. Created by Robert Behar and Rosario Marquardt, who work under the name R & R Studios, the 2001 installation arguably qualifies as the most widely recognised of their interventions in Miami, their adopted hometown since 1985.

Urban intervention and Miami icon 'The Living Room' by Robert Behar and Rosario Marquardt, 2001

Since then, R & R Studios has continued exploring subjects that 'The Living Room' captured so well, such as the scale (and more generally, the attitude) of public monuments, urban life, and the perceived permanence of cities in works like 'House of Cards' for the Miami Art Museum and 'All Together Now' in downtown Denver. Here, Behar and Marquardt delve deeply into 'The Living Room' and discuss how recurring themes in its work reflect the state of American cities as well as the relationship between artistic and architectural practice.

.....

Why would you say 'The Living Room' has become such an icon for Miami?

RB: Because, somehow, it is a mirror of Miami. One can see it as an unfinished event, a home that is still to be built. Or, from a different point of view, it is a ruin of a world that is no longer.

Also, in many ways 'The Living Room' restates the power of architecture and art, and speaks of architecture as an artistic endeavor rather than a real-estate proposition.

One could also simply read 'The Living Room' as a declaration: Miami lives outdoors.

RB: 'The Living Room' has the capacity to be interpreted at many levels. And although it’s architecture, 'The Living Room' posits an architecture that proposes questions rather than offers a complete solution. Is life outdoors possible? Would it be preferable?

By talking about the outdoors, we’re ultimately referring to civic engagement, right?

RB: ‘The Living Room’ is between private life and public life, where both collide yet expose each other.

RM: The domestic image of 'The Living Room' invites appropriation by the public. Perhaps this happens because, while 'The Living Room' is public space, it suggests a private dimension of life and ownership by everyone who engages the piece. The tension between the familiar and the exceptional is key for the project to remain open and meaningful.

RB: The word 'monument' comes from two words, one meaning admonition and the other memory. It encapsulates memory and admonition, the past and the future. 'The Living Room' has that capacity. One of the things we love about 'The Living Room' is that it’s a popular event in the neighborhood. The day we were most happy was when we saw a family from Haiti taking a family portrait in the living room. As if ‘The Living Room’ were theirs.

Detail of 'The Living Room', Miami, by Robert Behar and Rosario Marquardt, 2001

Do people catch themselves feeling too secure, private, in a public venue?

RB: It’s really weird, it has a life beyond us. As 'The Living Room' has grown in the context of the city, and people tell of their experiences and their encounters with it, we learn what it means. It has the capacity to tell many stories.

RM: And to capture the imagination of different people in different ways.

RB: Because that’s what Miami is very much about: there isn’t one story that tells the story of Miami. Perhaps there’s no need to find one story.

One example is that when you look at Miami from South America or the Caribbean, it looks like a capital – where there are skyscrapers, highways – but from New York it looks like a frontier town. It’s that double condition that makes it fascinating. That is true in every city to some extent, but it’s not part of the very origin of the city. We are at that moment, that foundational moment of the city. Compared to Venice, Miami is an overgrown kid. It’s only 100 years old.

Construction shots of 'The Living Room', Miami, by Robert Behar and Rosario Marquadt, 2001

Well, 'The Living Room''s iconic status extends beyond city limits. Why would it resonate with people hailing from other cities?

RM: I think the idea of an open home is what captures people’s imagination. And in the tropics, that is a real possibility.

There’s also a critical aspect. Today Miami is becoming enclosed, gated, and privatised, and forcing us to move in cars from one place to another. 'The Living Room' is a life without limits.

So you’re saying 'The Living Room' is a kind of subversion?

RB: It’s subversive because it poses questions. For too long we have lived in a society where questions are not essential.

Coming back to this question about the appeal of 'The Living Room' to non-Miamians, do outsiders understand all these nuances? To rephrase it, just think of Denver, Copenhagen, and the other cities that have commissioned your work: Are these clients asking you to peer into the idea of each city, tease apart its strengths and weaknesses, and perhaps produce a work that doesn’t entirely portray that city in a flattering light?

RB: The places that choose us, like Madison, Denver, Austin or Copenhagen – I think there is something there.

RM: What is it?

RB: They’re related. These are cities that have a vibe, an urge, for something else.

'All Together Now', Denver, by Robert Behar and Rosario Marquardt, 2007

They’re in the midst of transformations.

RB: Yes. Most architects and artists are afraid of speaking of an architecture of hope.

Do all these cities desperately need more public space?

RB: I think America is in need of public life in general. There is an incredible want for public life, for friendship, for meeting someone in the street and saying 'hi' – it’s a kind of mythical America that lives within each one of us. Our projects interpret that need, and help give it form.

RM: In contemporary cities, public space is very limited and generally without quality; you cannot be outdoors reading the newspaper. There’s no place to sit down, or take a nap in a park, shade is often missing and birds go elsewhere. The push is indoors and toward private commercial space. We are missing the sky, the clouds and everything else that makes everyday an adventure.

RB: Public life has been torpedoed to an incredible degree in America. Where there are benches, they are subdivided so that people cannot sleep on them. It’s so mean when you think about it. What if I want to take a nap? I could be misconstrued as a homeless person, and presumably a homeless person is dangerous.

Would you say, then, that fear is more powerful than this myth of American public life?

RM: We have this saying that, today, form follows fear.

RB: And we resist that proposition, because it is sad to live in a society of fear.

RM: Fear of the unknown and the new.

RB: And that fear reflects in the architecture of fear. We’re going to subdivide the bench, put up a gate, require an ID card. There’s this idea that by separating from each other we’re going to find a peace, and nothing can be more untrue. There’s nothing more fearful than to walk alone in the middle of the night. But if you’re in the middle of a carnival in the middle of the night, I don’t think anyone can feel fear.

When you’re dealing with municipalities or other clients, do you notice a point when the mythical-America desire overcomes the fear?

RM: Yes! It happens when there’s an image of the project, especially when it’s very powerful, such as 'All Together Now' or the 'Star of Miami'. It’s not easy, but clients, supporters, patrons, or even anonymous citizens always engage with clear, meaningful images.

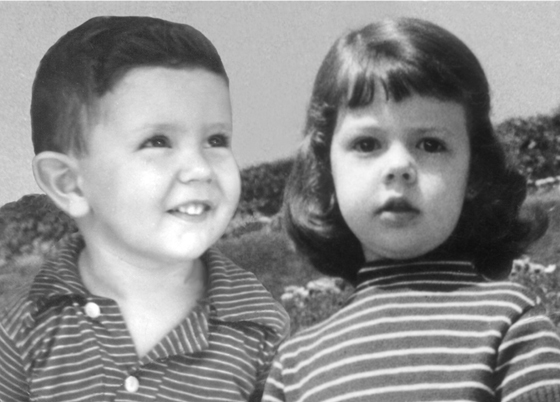

Portrait of artists Robert Behar and Rosario Marquardt

It sounds like an adult surrendering to the inner child.

RB: In psychological terms, absolutely. And it’s the overcoming of fear. People may not see that, but that’s OK. And it also makes a profit.

And clients respond to money.

RB: Exactly.

RM: What is good for the image of a city is good for the city.

I see shades of Googie and programmatic architecture in your work. Do you think you are evoking America’s inner child – the optimism of the country at mid-century – in doing so?

RB: I don’t think the origin is 1950s Americana, not aesthetically. I think what this work attempts to do is to collapse time: The warehouse wings flanking 'The Living Room' belong to a different time than the corner itself. But they’re woven together. It proposes that we don’t have to erase in order to build.

RM: For us is important to have freedom of style, freedom from what is in fashion at the moment.

Is mythical America at the centre of everything you do?

RB: I don’t think we need to search for a single answer any longer. I think we are at a stage where multiple answers may coexist in life. I am Roberto Behar, I am Argentine, I’m American, a Jew, an architect, an artist. I’m not one thing or the other, but all of those.

RM: There’s friction.

RB: Multiplicity is key. That’s accessible to people, but also interesting to the critical mind. Public and private, home and monument, popular culture and the avant-garde, stage and audience. It’s an imaginary solution for a better world.

RM: That comes with the theory of the exception: The core of metaphysics is the exception of the rule, not the rule itself.

RB: We don’t propose for everyone to do a living room, or star islands, or 'All Together Now', and to reproduce them ad infinitum. We propose them as exceptions, which suggest a possible course of action where differences coexist and give further meaning to life.

Thank you.