Anni Albers and the forgotten women of the Bauhaus

Texto por Dominic Lutyens

London, Reino Unido

13.03.19

The Bauhaus, the interwar German design school that profoundly influenced later developments in art, architecture, product design and typography, was a complex, contradictory crucible of ideas.

The women from bauhaus weaving workshop on the staircase of the Bauhaus building in Dessau,1927, Photo: T Lux Feininger Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin/ © Estate of T Lux Feininger

The women from bauhaus weaving workshop on the staircase of the Bauhaus building in Dessau,1927, Photo: T Lux Feininger Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin/ © Estate of T Lux Feininger

×Influenced by modernism and its rejection of artistic tradition and commitment to a socially democratic future facilitated by good, functional design, the Bauhaus was aesthetically forward-looking. Yet in practice the school, which closed in 1933 under pressure from the Nazi regime, was far from socially progressive.

Founded by architect Walter Gropius in 1919 on the principle of the Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art that fused art, architecture and design – the school theoretically treated these disciplines in a non-hierarchical way. In practice, however, the Bauhaus viewed architecture as the apogee of these fields, even though its architecture department didn’t open until 1927.

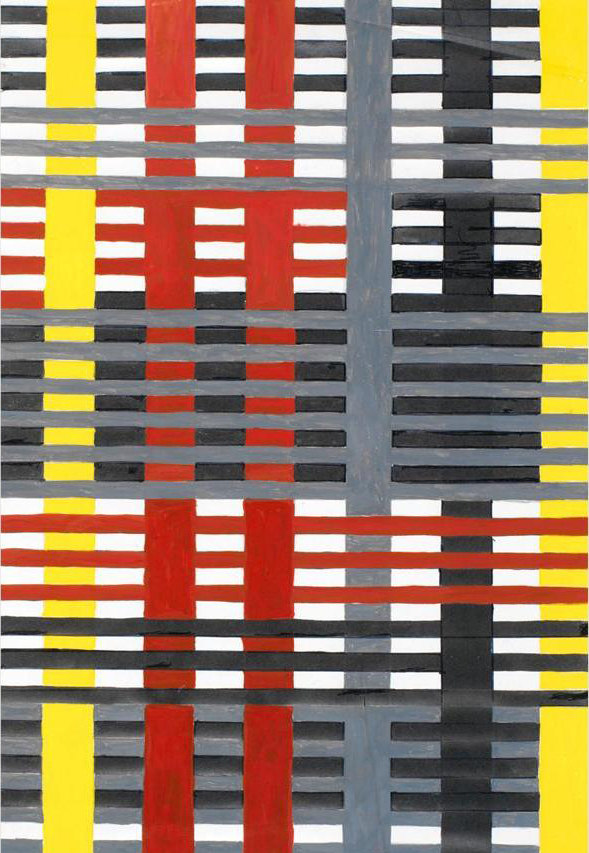

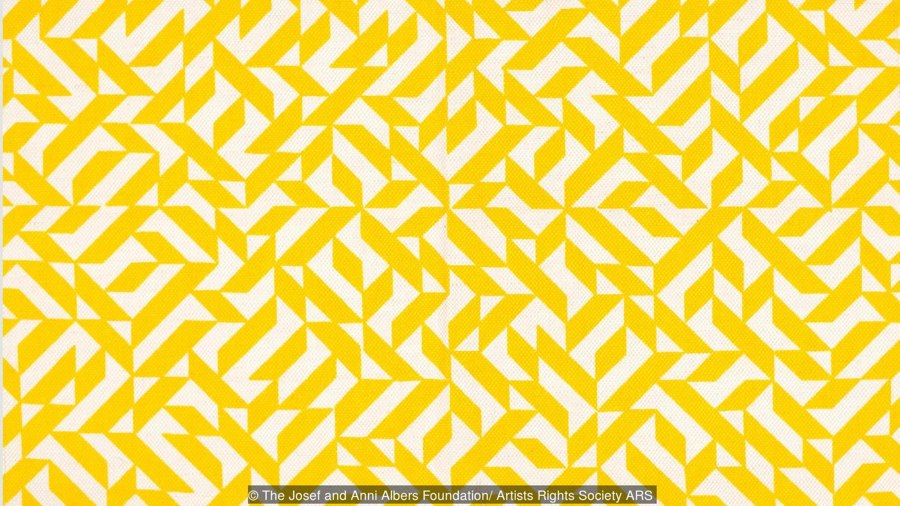

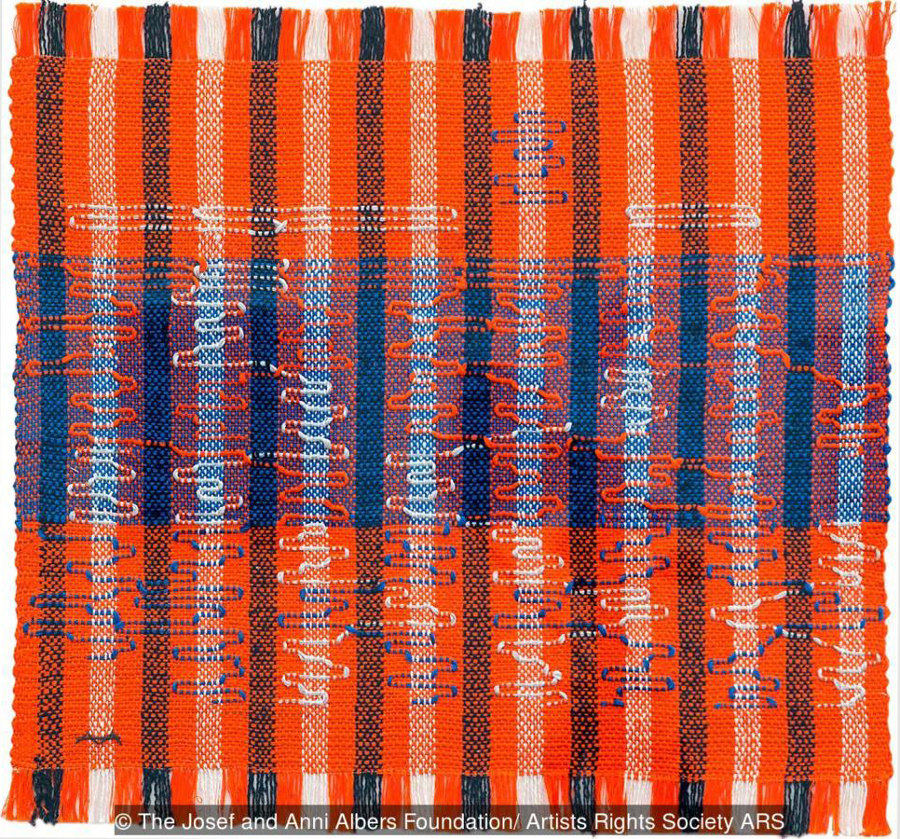

Anni Albers’ Wallhanging, 1926, is typical of the precise, geometric style of the Bauhaus. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

Anni Albers’ Wallhanging, 1926, is typical of the precise, geometric style of the Bauhaus. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

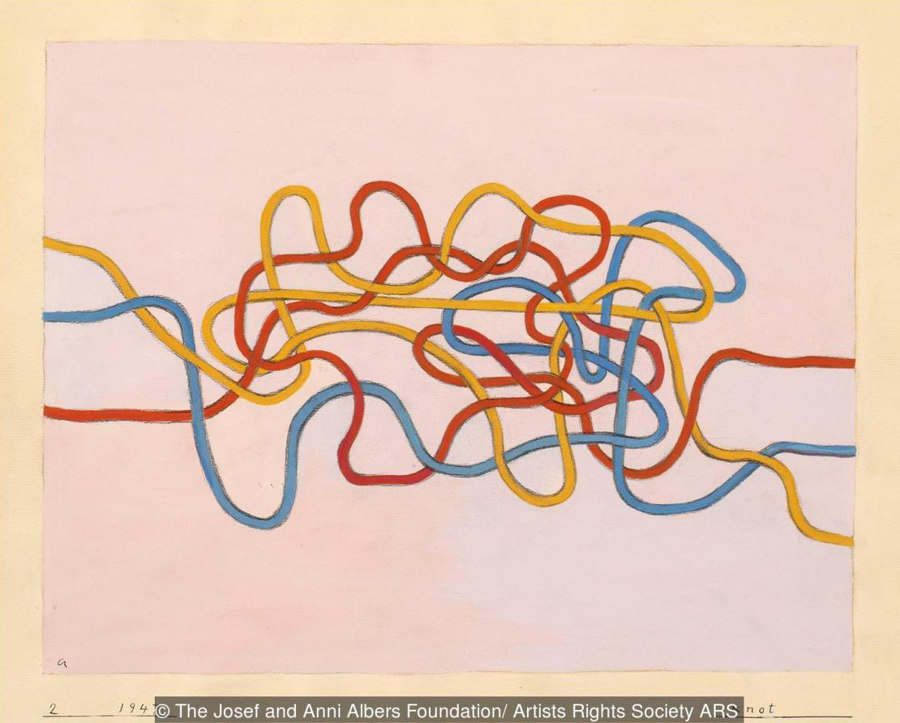

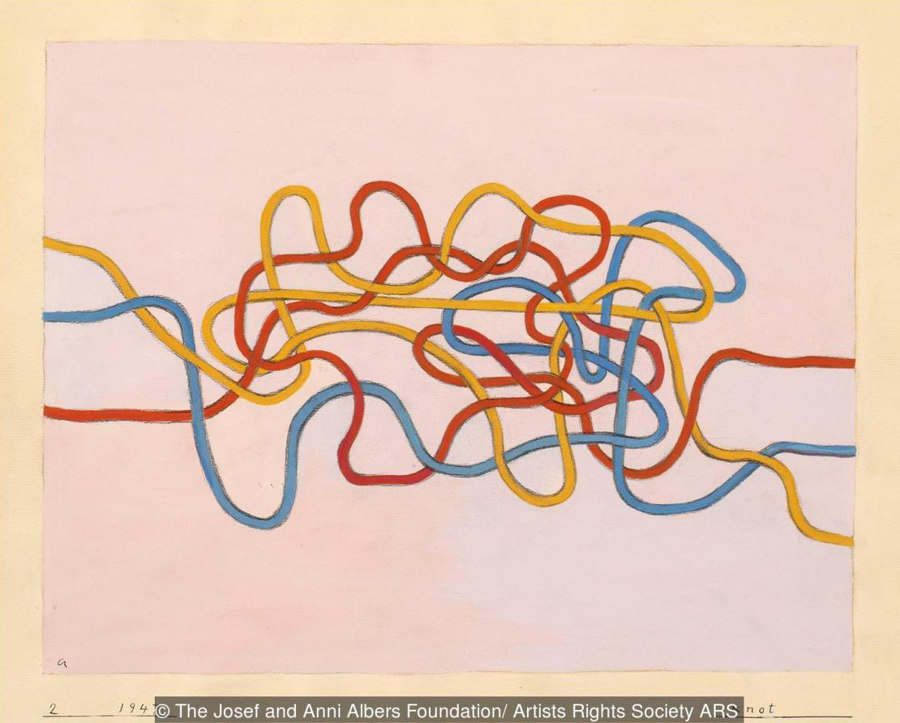

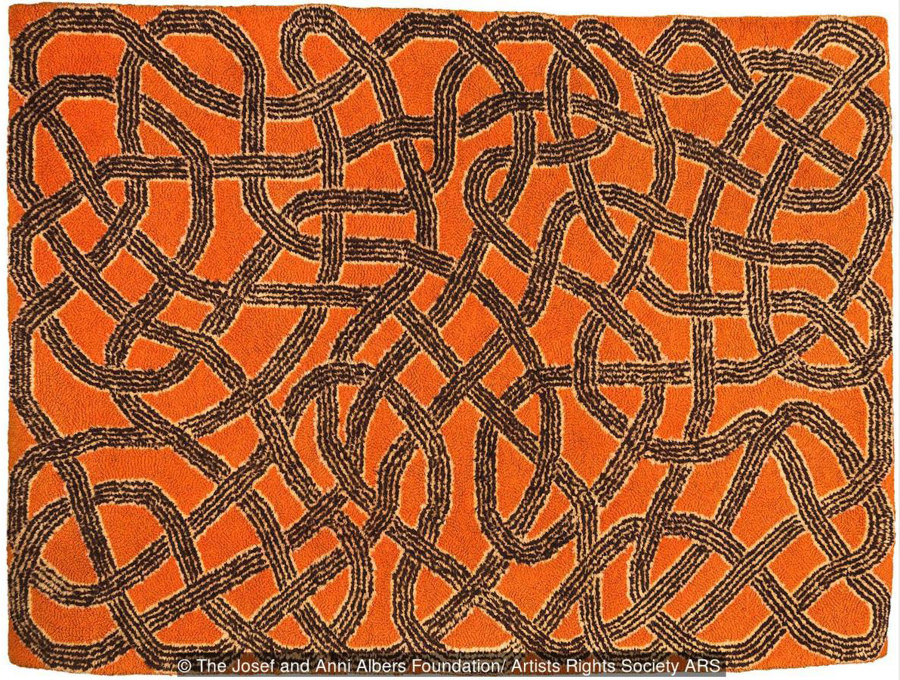

×Knot, 1947, is an example of Albers’ work at its most innovative. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

Knot, 1947, is an example of Albers’ work at its most innovative. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

×Its manifesto of 1919 welcomed “everyone without regard to age or sex” and that year more women than men applied to it. Tellingly, Gropius insisted that it would not discriminate between “the beautiful and the strong sex”. And while the Bauhaus gave women unprecedented access to art education, at its first location in Weimar only six out of its 45 teaching staff were women.

“For all its rhetoric, the Bauhaus was never the haven of equality that Gropius initially espoused,” says Libby Sellers, design curator and author of the book Women Design (Frances Lincoln). “Fearful of the impact women might have on the school’s professional reputation with industry, not only did Gropius subsequently place restrictions on the number of women permitted entry, but the increasingly reduced few were directed towards what were deemed more suitably feminine subjects, such as fine art, ceramics and weaving.

“Historians and commentators of the era, eager to emphasise modernism’s love affair with architecture and industrial design, often did so at the expense of other disciplines,” she adds. “Consequently, many designers working in textiles, ceramics, set design and interiors were often overlooked.”

Aside from Sellers, German academic Ulrike Müller laid bare this rarely acknowledged inequality between the sexes in her 2009 book Bauhaus Women: Art, Handicraft, Design (Flammarion). While many men at the Bauhaus – among them architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who led the school from 1930 to 1933, artist Paul Klee, painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, and furniture designer Marcel Breuer – are considered design titans today, their female counterparts are relatively unknown.

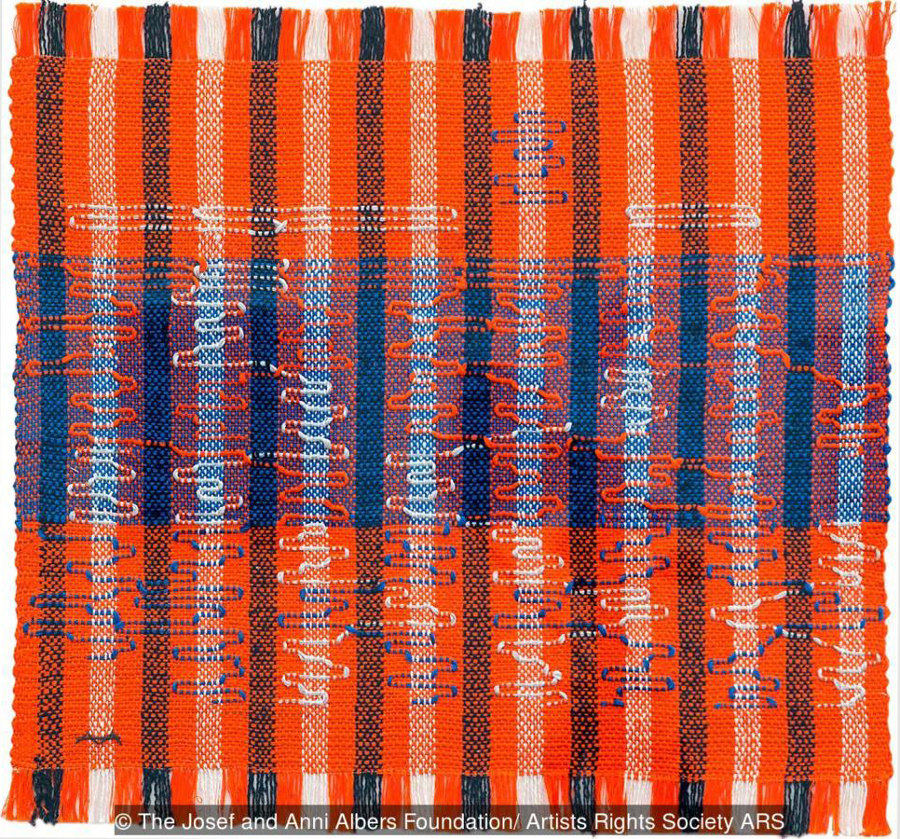

Anni Albers’ weaving was hugely innovative, even though it was not her first choice of design medium. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

Anni Albers’ weaving was hugely innovative, even though it was not her first choice of design medium. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

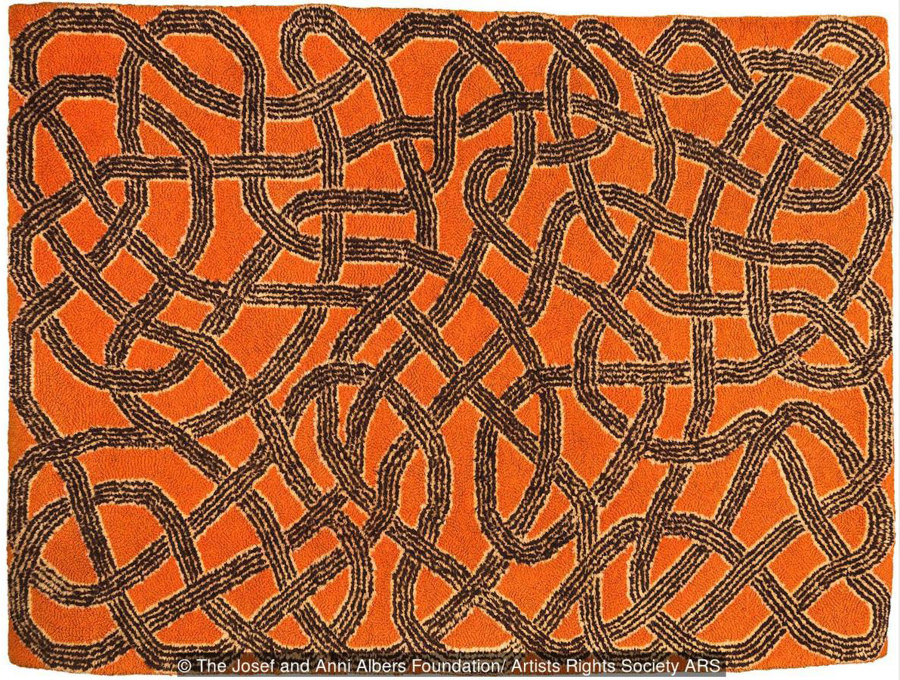

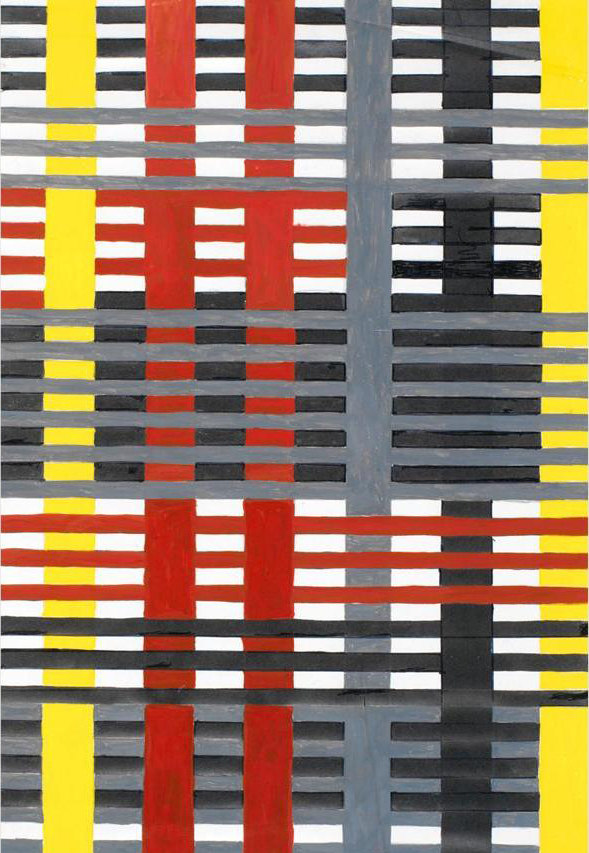

×A wool, hand-woven rug by Albers, created in 1959, is one of the exhibits at the Tate exhibition. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

A wool, hand-woven rug by Albers, created in 1959, is one of the exhibits at the Tate exhibition. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

×The most famous is Gunta Stölzl, head of the weaving workshop from 1926 to 1931. Another name is Anni Albers, who became head of the weaving department in 1931. Albers (née Fleischmann), born in Berlin and of Jewish descent, was typical of the school’s alumnae; for this independent, ambitious artist and designer, studying there was an act of rebellion against her conventional, affluent family. But at the Bauhaus she found herself barred from the glass workshop she hoped to join. Although she took up weaving reluctantly, she went on to become a pioneering textile designer.

Meanwhile, the androgynous Marianne Brandt, the first woman to be admitted into the Bauhaus’s metalwork department, found fame when she created her commercially successful, iconic 1920s Kandem bedside lamp and Constructivist-inspired coffee sets.

In 1933, Albers escaped Nazi Germany, moving with her painter husband Josef Albers to the US, where architect Philip Johnson invited them to teach at the avant-garde art school, Black Mountain College, North Carolina, attended by such luminaries as artist Robert Rauschenberg and architect Buckminster Fuller. In 1949, she gained further recognition as the first designer to have a solo show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and she produced textiles for such companies as Knoll and Rosenthal.

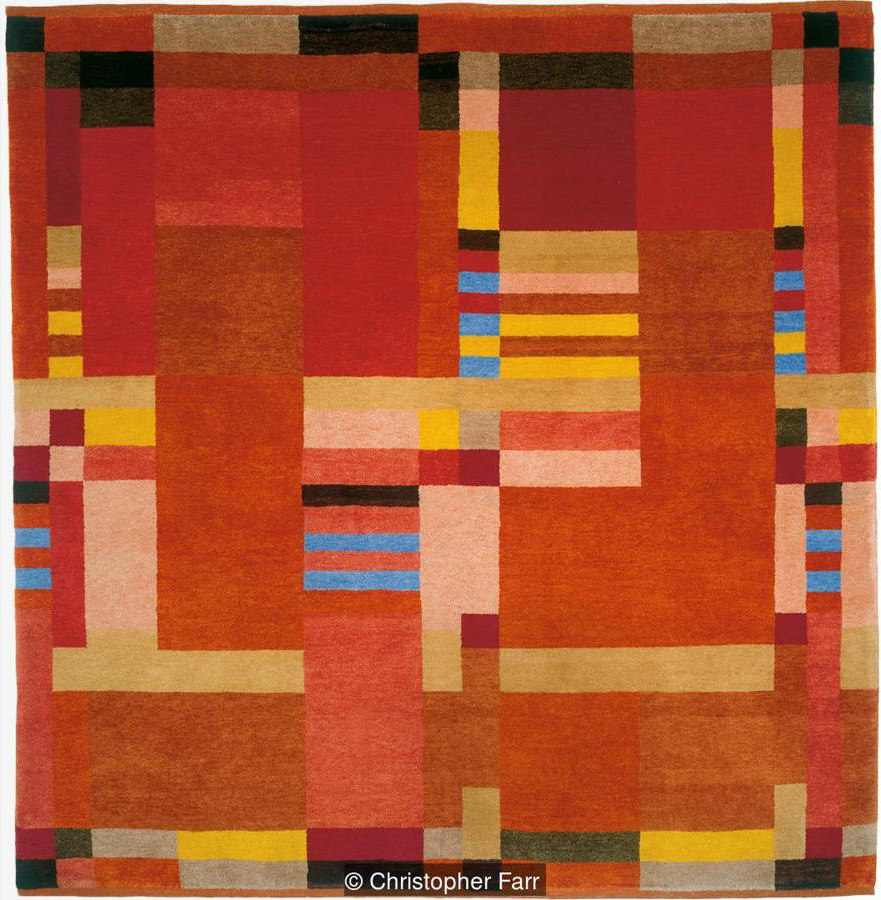

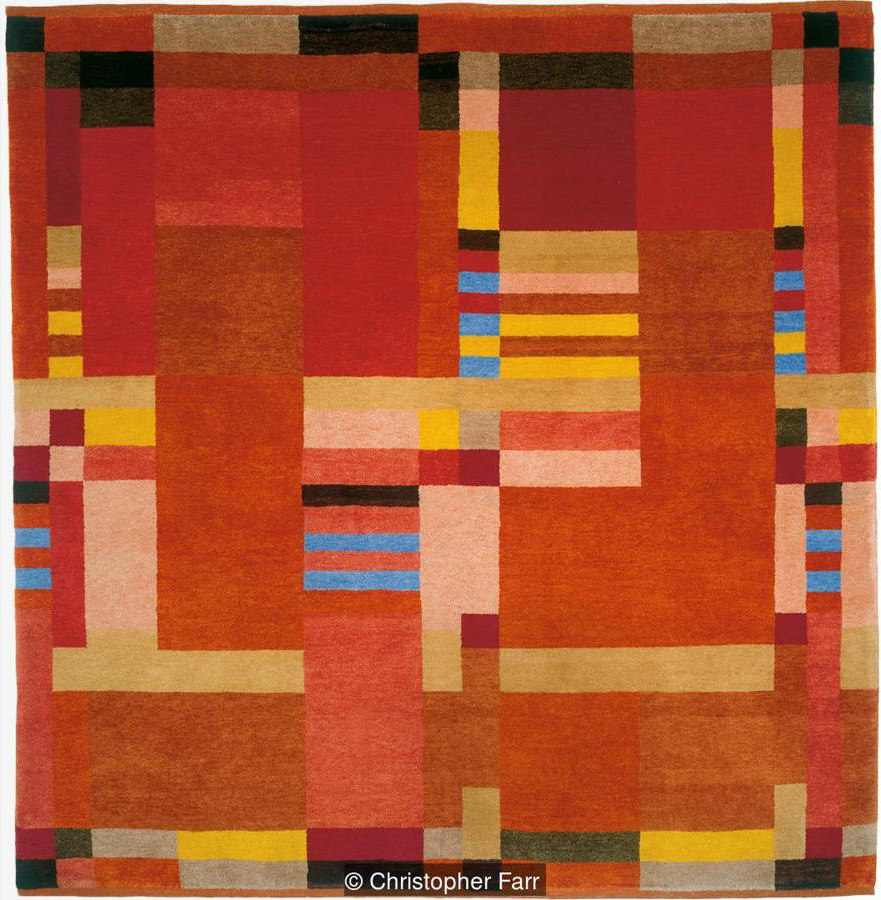

The designs of Gunta Stölzl have been reproduced on rugs made by Christopher Farr Cloth. © Christopher Farr

The designs of Gunta Stölzl have been reproduced on rugs made by Christopher Farr Cloth. © Christopher Farr

×For all the Bauhaus’s shortcomings, its radically cutting-edge teaching appealed to Albers, who was greatly influenced by Klee, famous for his description of drawing as “an active line on a walk, moving freely without goal”. Her own, similarly freewheeling approach oscillated between fine art and ambitiously monumental, functional pieces used in an architectural context.

Albers, who died in 1994, was also a passionate advocate of weaving, as articulated in her books, On Weaving and On Designing. Now Tate Modern is holding a major exhibition of her work, which also includes her experimental prints and drawings.

The exhibition also includes examples of Albers’ ‘pictorial weavings’, made from the 1930s to the 1960s, many of which were influenced by trips she and her husband made to Mexico, Peru and Chile. Her aim with these, she said, was “to let threads… find a form themselves to no other end than their own orchestration, not to be sat on, walked on, only to be looked at”.

“Albers had a strong interest in architecture and its relationship with textiles,” says the show’s curator Ann Coxon. “In 1928, she began working on a massive, soundproof, light-reflecting fabric incorporating cellophane and chenille for the auditorium of the Bundesschule des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes, the ADGB Trade Union School, designed by Bauhaus architect Hannes Meyer. A piece of this textile will be displayed in the exhibition. Years later, in her 1957 essay, The Pliable Plane, Albers argued that all primitive forms of architecture, such as tents and yurts, were based on textiles.”

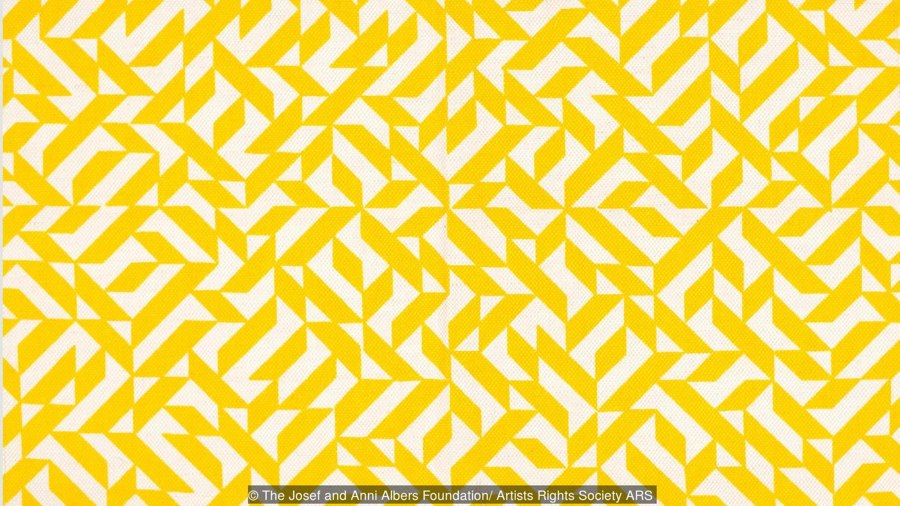

A silkscreen on woven fabric, Eclat, 1974, showcases Albers’ bold use of colour. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

A silkscreen on woven fabric, Eclat, 1974, showcases Albers’ bold use of colour. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society ARS

×In 1971, the couple set up the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, which has long collaborated with British rug-and-fabrics company Christopher Farr Cloth, reinterpreting textiles from her archive. One of these, Orchestra, reissued to coincide with the exhibition, typifies Anni’s playful approach: its print, inspired by childhood trips to the Berlin Opera, was created by cutting stripes painted onto fabric into lozenge shapes that were repositioned to form an apparently random pattern.

“Brilliant young women were drawn to the Gropius-led Bauhaus with dreams of becoming architects, only to be informed, falsely, that weaving was the only appropriate discipline for women,” says Farr, whose company has also reproduced rugs by Gunta Stölzl since 1997. “However, architecture’s loss was textiles’ gain, and this as it turned out was a tremendous gift to 20th-Century textiles and put Anni Albers firmly into the premier ranks of celebrated modernists.”

This article was first published on BBC Designed