Master Meets Machine

Texto por Frame Publishers

Holanda

05.09.13

Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa’s designs for Maruni show the brand’s expertise in mass-producing high-quality wooden furniture.

‘While there are artisans who can make a beautiful wooden chair entirely by hand, but a product that comes with a high price tag, we are using both machinery and manual crafts to make equally beautiful wooden chairs that are affordable. Our vision is to industrialize craft,’ says Takeshi Yamanaka, the president of Maruni Wood Industry.

In Hiroshima City, 900 km west of Tokyo, Maruni Wood Industry’s 100 skilled craftspeople – experts in working with wood – turn out a constant supply of wooden furniture that defies any notion of fashion or national borders: the company reaches 20 countries around the globe, including those as far afield as Lebanon. Since its establishment in 1928, Maruni has not flirted with other materials, such as metal or plastic, but has focused solely on the production of wooden items. Frame talked to Takeshi Yamanaka about the history of the company, as well as its future.

Jasper Morrison originally designed the Botan bench for his terrace five years ago. Maruni launched a mass-produced model in cedar at the 2013 Salone del Mobile

Jasper Morrison originally designed the Botan bench for his terrace five years ago. Maruni launched a mass-produced model in cedar at the 2013 Salone del Mobile

×Could you tell us about the company’s background?

Takeshi Yamanaka: My grandfather’s brother founded the Showa Bentwood Factory in 1928, which was later named Maruni Wood Industry. He wanted to offer Western-style furniture, which was considered to be a symbol of sophistication at that time in Japan. We started by replicating Michael Thonet’s bentwood chair. Our founder was mesmerized by its innovative design, which was suitable for mass production and relatively easy to process. Hiroshima Prefecture, where our company is based, has been a big supplier of timber to a nearby shrine for more than 1000 years, so we have always had a wealth of supply chains for timber, which gave us the perfect background for starting a business in wooden furniture.

How did Maruni come to specialize in processing wood?

It was during the Second World War, when we briefly shifted our production to cater to the war industry. We made wooden wings for aeroplanes, an opportunity that allowed us to develop and refine wood-machining technology. After the war, we focused on making wooden furniture in a classic Western style, creating cabriole legs and curvaceous forms that exploited our machining technology. Before the war, the majority of the Japanese people weren’t used to seating furniture, as we sat on tatami mats on the floor. But after the war, during a period of economic growth in Japan, our ornate pieces met the needs of a population that wanted substantial furniture to show off with.

Classic furniture is quite different from what you produce today. How did that shift come about?

Although we applied machine production to our manufacturing process, the majority of the finishing needed to be done by hand. That made our furniture luxury items. In the 1990s, when the Japanese economy plunged, our sales plunged as well. We had to slim down the factory, and that’s the moment I was brought in to shake up the company. The first thing I did was to make a total change in the type of furniture Maruni was manufacturing.

That brings us to the new Maruni projects. Why do you work with outside designers, and how did you select them?

When I became Maruni’s product development manager, the company was in a critical state. I thought that breaking away from the classic furniture we had been making for nearly 70 years and introducing totally new designs would also mean a change in customers. I envisioned a new market opening for us. I am part of the third generation at Maruni, however, and I don’t have a design background. So I started talking to many designers and architects, including product designer Masayuki Kurokawa. Having been to our factory many years ago and knowing the quality of our wood processing, Kurokawa suggested that we ask designers to make pieces that would exploit our technology and explore Maruni’s ‘next standard’. He started the Next Maruni project. We invited 12 designers – among whom Alberto Meda, Harri Koskinen and Sanaa – to design a chair for Maruni. It was a good experience for us, an exploration of how our technology could be manipulated with design and an understanding of how certain foreign designers viewed Japanese wooden furniture. We first introduced our Next Maruni collection at the Milan Furniture Fair in 2005. That launch coincided with Maruni’s first thoughts on moving into the global market. We learned quite a bit from that project and from our new insight into the perspective of foreigners. However, not all the Next Maruni designs properly utilized our woodworking technology.

Hiroshima Chair by Naoto Fukasawa is Maruni’s bestselling product; photos Yoneo Kawabe

What led to your collaboration with Naoto Fukasawa?

Naoto Fukasawa had designed a chair for Next Maruni and had visited our factory. When we finished the Next Maruni project, which lasted for three years, we wanted to work with one designer with whom we could share our vision. We wanted to aim the company in a new direction. Everyone I asked recommended Fukasawa. When I knocked on the door of his office in 2007, it was as if he had been waiting for us to call him. We were nearly in a state of bankruptcy, so our proposal wasn’t lucrative for him at all. Fukasawa talked about the difference between making a wooden chair and making electrical appliances for the home. While the design and quality of appliances are driven by the latest technology – technology more of less determines the design and function – it is really the craftsperson’s experience and deep understanding of material that goes into making a good wooden chair. Recalling his years of experience with overseas furniture makers, Fukasawa pointed out that Maruni’s strength and assets lie in a combination of handicraft and high-quality machinery technology, which is hard to beat in the sphere of global industry. He suggested that Maruni focus on revealing the structure of a chair, causing machined wood and hand-finished details to stand out. Our collaboration resulted in the Hiroshima chair in 2008. This design was a giant leap for us, a company still firmly rooted in classic furniture featuring dark wood and thick upholstery. Fukasawa’s Hiroshima chair exposed the true colour and bare structure of the material. Nothing was disguised. Our factory workers and engineers were bewildered when they saw the design.

Could you describe the process between Maruni and its designers?

After a discussion about our company and our vision, designers come up with a concept. When the first design drawing is presented, I never turn it down. At that point we make a prototype, no matter how structurally weak or unfeasible that design is, because I don’t want to reject the designer’s initial vision. I tell the craftspeople to try to make it, and then we discuss what has to be changed. For example, a design drawing often doesn’t indicate things like joints, the direction of the grain, the tonality of the wood, et cetera – all very important elements in furniture by Maruni. Issues such as the use of cross grain rather than straight grain on visible parts of the chair, or the position of dovetails, are suggested by Maruni. After the designer modifies the design in line with our recommendations, we make another prototype, examine it, and move on to the following discussion. We ended up making 30 prototypes of the Hiroshima chair. It’s like a game of catch: designers, craftspeople and programmer toss the ball back and forth. Each has an equal stake in the design process.

What is the role of the programmer?

The difficult part of Fukasawa’s design involved quantifying the subtly curved lines of the Hiroshima chair and developing a computer program for the machine that would make the chair. It is the program engineer’s job to develop a computer program for the numerically controlled machine, which has to perform the same intricate task that is demanded of a highly skilled artisan. Fukasawa is known for making full-size models of the products he designs. His staff used Styrofoam for the first model of the Hiroshima chair. It’s one thing to carve a model out of Styrofoam, and a totally different thing to replicate the same design using serial production. You need a computer program for that. It took us three months to develop the software for Hiroshima, and after the first chair had been made, the program was modified some 45 times. The design doesn’t change, but we are constantly looking for more efficient ways to produce a chair that is even more affordable.

What is Maruni’s vision? What does the company want to achieve?

Our vision is to industrialize craft – to integrate craft and industry. We don’t deny using machines, nor do our designers. Rather than compromising on quality, which never happens at Maruni, we utilize both machine production and manual craft as needed. We do this in order to offer masterfully made furniture at a good price. There are craftspeople who can probably make a chair of this quality with their hands, but that chair would be far too expensive for most people.

Maruni Wood Industry utilizes both machine production and manual craft

Have you run into any difficulties in recent years?

After introducing Hiroshima in Milan in 2008, we still didn’t have a distributor. I approached Isetan, Japan’s top department store, and explained how the design was made. Isetan agreed to carry the chair, but for three or four months no one showed any interest in the product. At the time, most Japanese people didn’t recognize the name Naoto Fukasawa. Our staff and the people at Isetan spent a lot of time communicating the story of the Hiroshima chair to potential customers. We had come to realize that a good product doesn’t just speak for itself. We need to tell the story behind it.

In 2011 Jasper Morrison joined Maruni as a designer.

Jasper Morrison had been to our factory in 2004 with Fukasawa, and since then he’s been an advocate for our company. Although he didn’t design anything new this year, Morrison did show us a bench that he’d designed for his terrace five years ago. He wanted to have the design mass-produced. We were extremely flattered to learn that he felt a bench designed for his personal use would fit into Maruni’s philosophy.

What is Maruni’s strategy for the years ahead?

It is not a new strategy, but something we always keep in mind. We want to make chairs that will last a century, because we use timber that is over 100 years old. It’s a ambition we share with both Fukasawa and Morrison. To achieve this goal, we consider each design very carefully, in the realization that it has to defy the notion of time. At the same time, we pay close attention to the durability of the structure of our furniture. And we continue to improve programs for the machinery that makes the furniture, with an eye to keeping our products affordable and perhaps even lowering the price in the coming two to three decades.

The latest piece in Jasper Morrison’s Lightwood collection for Maruni is an armchair; Morrison added armrests to his existing Lightwood chair, using similar structural elements and jointing techniques

The latest piece in Jasper Morrison’s Lightwood collection for Maruni is an armchair; Morrison added armrests to his existing Lightwood chair, using similar structural elements and jointing techniques

×Expertise in Wood

‘These days it’s quite rare to work with a company that manufactures its own products. Most companies use a variety of sub-suppliers to provide a wide range of manufacturing possibilities, but in the case of Maruni, the subject is wood, and they have all the facilities and skills needed to manufacture their own products. The difference is that their quality is consistently high, and it’s easier to discuss the possibilities and ways of making a new design. Apart from that, they are based near Hiroshima, and we go out to eat blowfish after meetings . . . ’ Jasper Morrison

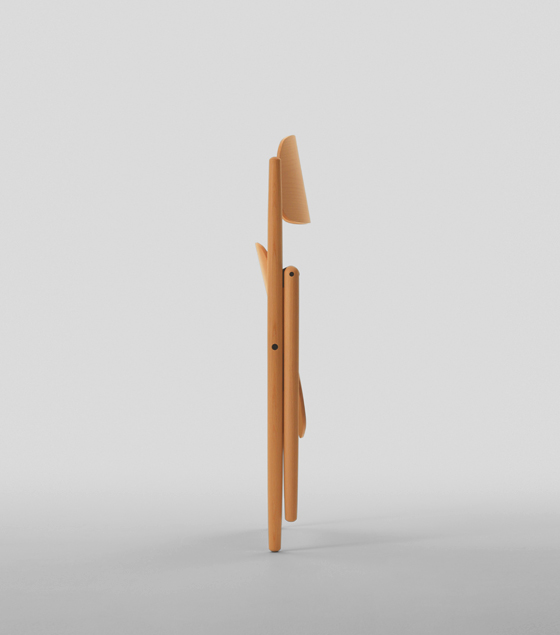

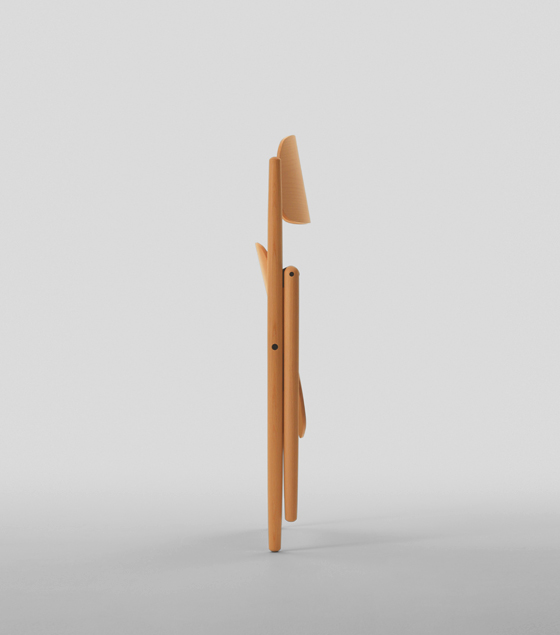

Noato Fukasawa’s Hiroshima collection for Maruni now includes a folding chair in beech with a silky surface.

Noato Fukasawa’s Hiroshima collection for Maruni now includes a folding chair in beech with a silky surface.

×East Meets West

‘For a designer, creating a chair is very special. The design of a wooden chair is about more than just the beauty of the form. It’s also about knowing the different nature of each wood and about understanding how different parts of the wood can be combined. The savoir-faire needed to figure out the best structure, the most effective use of the wood grain, the ease of maintenance – all these elements need to be orchestrated into making a single wooden chair. Japanese woodworking skills are superior, but Maruni also stands out because of its extensive history in making decorative chairs with a Western influence. This allows the company to combine Western and Japanese techniques when making their chairs.’ Naoto Fukasawa

Fukasawa asked himself: Why not add a folding chair to the Hiroshima series – a chair that creates a perfect image when placed against the wall?

Fukasawa asked himself: Why not add a folding chair to the Hiroshima series – a chair that creates a perfect image when placed against the wall?

×––

Maruni Wood Industry Inc.

Website maruni.com

Location 24 Shirasago Yuki-cho, Saeki-ku, Hiroshima, 738-0512 Japan

Established 1928

Number of employees 230 (December 2012)

Distribution Worldwide

Market sector Furniture

Annual turnover €22 million

Best-known product Hiroshima arm chair

Bestselling product Hiroshima arm chair

Collaborating designers Maruni Collection: Naoto Fukasawa, Jasper Morrison; Next Maruni: Alberto Meda, Harri Koskinen, Jasper Morrison, Kanji Ueki, Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa (Sanaa), Masayuki Kurokawa, Michele De Lucchi, Naoto Fukasawa, Jutamas Buranajade + Piti Amraranga (o-d-a), Sean Yoo, Shigeru Uchida, Shin Azumi, Tamotsu Yagi, Tetsu Sumii, Tomoko Azumi, Nendo

––

Text: Kanae Hasegawa

––