'Harmonious Anarchy': revisiting Hak Nam, Hong Kong's slum city

Texto por Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suiza

09.04.10

When photographer Greg Girard decided to visit the notorious, citadel-like 'Walled City' slum in Hong Kong's Kowloon, where the daily lives of 35,000 people played out, he was told he may not come back alive. Luckily for him, he did. And, luckily for us, he brought with him a series of compelling images, showing just how close the relation between architectural space and social behaviour can be.

In his 1972 novel 'Invisible Cities', Italo Calvino uses the conceit of the explorer Marco Polo describing the imagined, yet seemingly physically impossible, cities he has encountered on his travels to, in turn, explore the workings of imagination itself. Fantastical urban scenes are described, such as the city that is a thin as a sheet of paper, but which 'seems to continue, in perspective, multiplying its repertory of images', or the city that consists merely of the props of its construction (cranes, scaffolding, 'beams that prop up other beams') and nothing else.

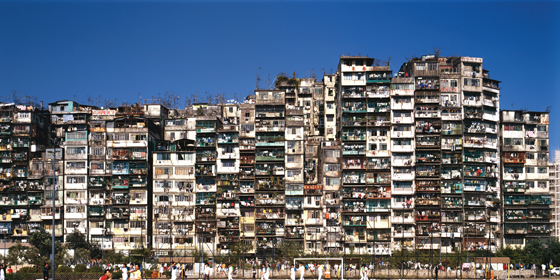

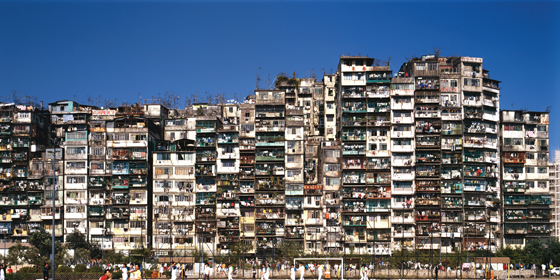

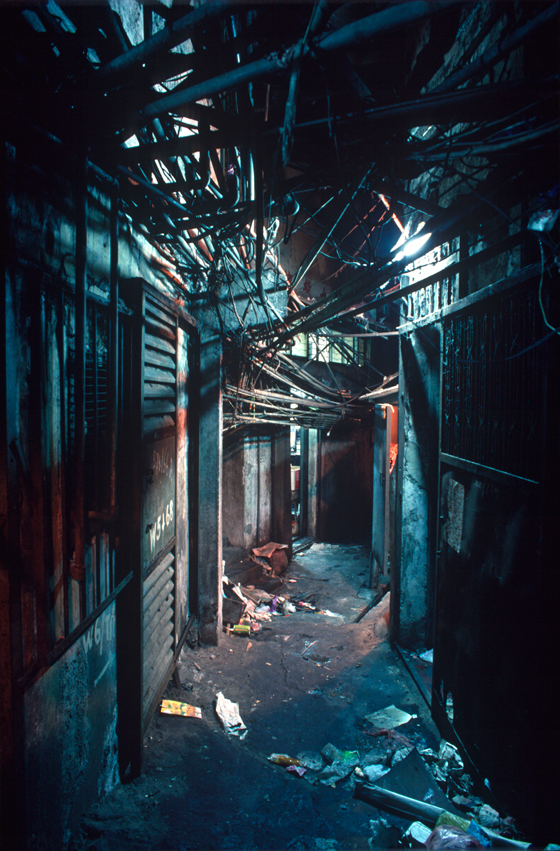

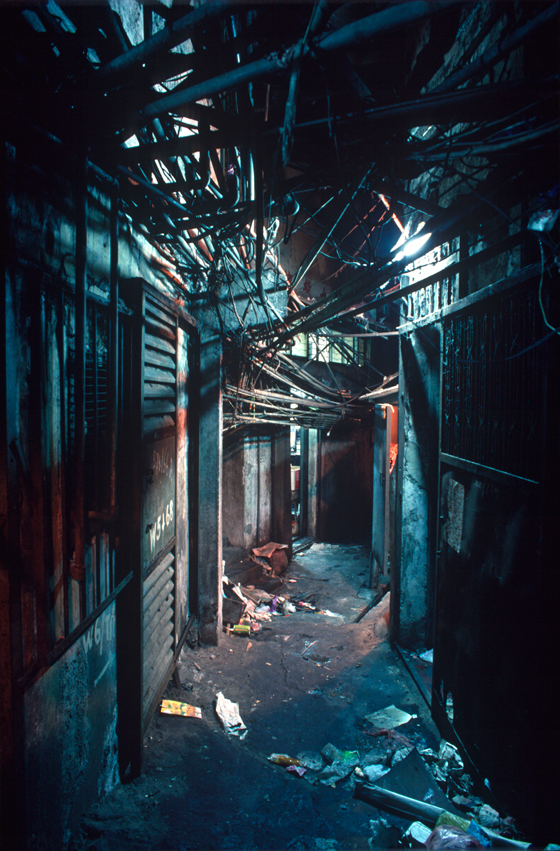

Hak Nam, the giant slum city in Hong Kong's Kowloon that was torn down in 1993, could almost be one of Calvino's urban dreams. Like a depiction from the Middle Ages of some ancient, towering city, the structure was at once awe-inspiring and unnerving in its scale and squalor. With 35,000 people living in a series of cheek-by-jowl buildings up to 14 floors in height, circulation permitted by labyrithine passageways full of rubbish, 'the Walled City', as it was known, would have tested even the most enthusiastic of those early-20th-century Modernist proponents of 'Existenzminimum'.

Vancouver-based photographer Greg Girard visited Hak Nam several times in the late 1980s, in spite of warnings that he was putting his life in danger (the place was renowned for its criminality), recording both the physical and the social fabric of the settlement, and the relation between the two. The fact that Hak Nam, in architectural terms, grew organically over time according to its inhabitants' needs, as opposed to being constructed according to a pre-existing blueprint, made the city's take on ordered chaos particularly compelling. As new-comers arrived, changing the social make-up of the community, so their built environment changed.

'City of Darkness', a book of Girard's Hak Nam photographs, was published in 1993 (Watermark Publications), offering a series of compelling tableaux of life within the citadel. All of humankind could be found here, apart from the police. Their visits were few. Beyond the criminals, drug addicts and prostitutes, a micro-society operated with its own shops, doctors, factories and schools. And all under a pall of Dickensian darkness. As the book's blurb puts it: 'Through a continual process of demolition and rebuilding – with never an architect in sight – individual buildings gradually homogenised. Only at street level did the old grid of public alleyways still exist, but hemmed in and built over: dark, dirty and squalid.' Yet somehow it all worked.

Looking at Girard's Hong Kong photography here in the Architonic offices puts us in mind of Le Corbusier's city-in-the-sky building type, the 'Unité d'Habitation', first completed in Marseilles in 1947 and then reiterated over the next twenty years in Nantes, Berlin, Briey and Firminy. With its density of dwellings, 'internal streets', and accommodation of social and communal functions (such as nurseries, medical facilities and recreational spaces) in the housing block itself, here, too, are communities, albeit on a smaller scale, that are organised spatially and socially in a homogenous way.

The difference, of course, between the Swiss architect's highly ordered schemes and the Kowloon slum city is that latter seemed to privilege disorder. Yet, in its organic growth, it also followed a particular logic. It was just a different one. (Possibly a more democratic one?) Both the 'Unité d'Habitation' (now so highly fetishised in architectural-historical terms, particularly by the large number of its architect-occupants) and Hak Nam have their particular cultural signficances. Valuing one over the other is a futile exercise. The Walled City, for all its confusion, was a system that seemed to function. Daily lives were led there. As the the owner of a chemist's told Girard on one of his visits, Hak Nam was a place of 'harmonious anarchy'.

.....

'City of Darkness'

Published by Watermark Publications

Softbound

216 pages

270mm x 275mm portrait

360 photographs, 320 in colour

English only

First published in 1993; last reprint 2003

ISBN: 1 873200 13 7