Concrete in Architecture (1): a material both stigmatised and celebrated

Texto por Susanne Fritz

Suiza

04.10.10

Almost no other material manages to carry such contradictory associations. Stigmatised on the one hand, celebrated on the other, it evokes highly diverse reactions. The word 'concrete' was used for the first time in 1750 by Bernard Forêst de Bélidor as a description for a mortar, in his book 'Architecture hydraulique'. The first ferroconcrete structures were built around 1900. Today, reinforced concrete is Germany's most important building material, with over 100 million cubic metres of it used every year. Its potential seems almost inexhaustible and continual innovations in how it's applied make it a valuable material for new architecture concepts. What follows is a look at concrete, related new technologies and a selection of interesting projects that have embraced these.

Brutalism in 'béton brut': Ministry for Road Building in Tiflis, Georgia, George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania, 1975

Brutalism in 'béton brut': Ministry for Road Building in Tiflis, Georgia, George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania, 1975

×What actually is concrete? Basically, concrete consists these days of cement, water and a stone aggregate:

cement, a hydraulic-setting binding agent, produces a cement paste when mixed with water, which is then enriched with a stone aggregate. The paste envelopes the small pieces of stone, fills the hollows and makes the wet concrete workable, until it hardens through hydration. The concrete then stays rigid, even under water and has a stable volume.

Reinforced concrete has led to a revolution in architecture. Steel possesses a high tensile strength, unlike concrete, and therefore makes large spans possible, without the need of arching. Its image as a cold and inhuman material was particularly prevalent in the 1970s. The repetitive way the elements were put together and monotonous housing silos contributed to this, as well as the way in which exposed concrete ages, often perceived as unaesthetic. 'Béton brut' architecture led to the term 'brutalism'. The association of brutality always accompanies the term, which makes the image of exposed concrete quite clear.

Neo-Brutalism in Winterthur, 2010. The façade with its relief mitigates the large surfaces of exposed concrete. The stencils used here are made by Noeplast

Neo-Brutalism in Winterthur, 2010. The façade with its relief mitigates the large surfaces of exposed concrete. The stencils used here are made by Noeplast

×But reinforced concrete was made famous much earlier through its delicate and highly elegant use in the shell constructions of Heinz Isler (Swiss building engineer, 1926–2009) and the bridges of Robert Maillart (also a Swiss building engineer, 1972–1940). The Isler system is still used today for working out shell constructions. Ulrich Müther realised numerous shell constructions in the 1960s in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, which, today, have an almost cult status.

Deitingen service station on the A1 Zürich–Bern. Load-bearing shell by Heinz Isler, 1968

Binz Beachwatch's rescue tower on the island of Rügen, a shell construction by Ulrich Müther, completed in 1968 and renovated in 2004

Binz Beachwatch's rescue tower on the island of Rügen, a shell construction by Ulrich Müther, completed in 1968 and renovated in 2004

×Over the course of decades, the volume of concrete and the amount of the material used has been continually reduced, thanks to better calculation methods and formwork techniques. But concrete hasn't only proved itself as a material for static substructures: colour pigments, additives and new techniques in working the surface have seen exposed concrete enjoy a renaissance for some time now, and it is being used more and more as an architectural skin: façades, floor surfaces, furniture – the possibilities of application seem to be endless. Architonic would like to demonstrate just how adaptable this fascinating material is with the following products and projects.

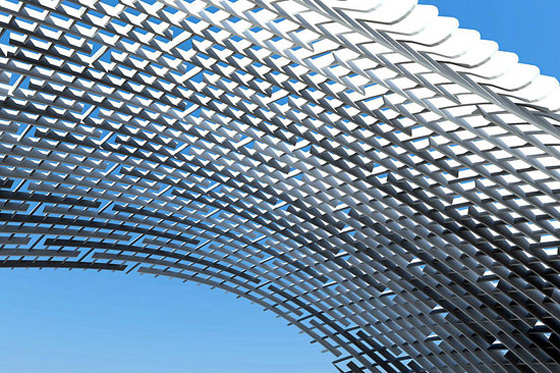

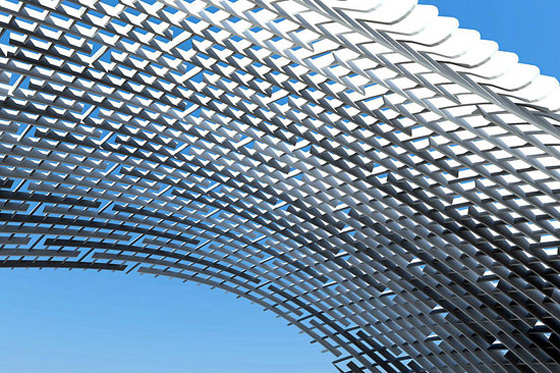

fibreC fibreglass concrete, made by the Reider company, used here for the [C]SPACE Pavilion in London, designed by Alan Dempsey and Alvin Huang, 2008

fibreC fibreglass concrete, made by the Reider company, used here for the [C]SPACE Pavilion in London, designed by Alan Dempsey and Alvin Huang, 2008

×It's not only steel that can work to improve the static qualities of concrete. Concrete reinforced with fibreglass allows not only thin cross-sections but also plastic forms to be realised. A spectacular example is the temporary '[C]space – DRL10' pavilion by Alan Dempsey und Alvin Huang, which was constructed in 2008 for the first time in London's Bedford Square. The construction consists of, in total, 850 unique, 13mm profiles, made of fibreglass-reinforced concrete ('Fibre C'), produced by the company Reider Faserbeton Elemente – hence the name of the pavilion. The competition-winning project, conceived to mark the tenth anniversary of the renowned Architectural Association Design Research Lab, was built from 30 tons of concrete and seven tons of steel.

Transparent concrete elements by Licatron. Light conductors are woven into the concrete

Textile concrete, which means concrete reinforced with webbing, possesses a substantially higher load-bearing capacity, compared with fibreglass-reinforced concrete. Both types of concrete have the advantage of being able to be used to create extremely thin walls, because their reinforcement, as opposed to steel, doesn't require a minimum amount of concrete cover.

fibreC fibreglass-concrete elements mit Bayferrox® pigments, used for Soccer City stadium, Johannesburg, designed by Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners

fibreC fibreglass-concrete elements mit Bayferrox® pigments, used for Soccer City stadium, Johannesburg, designed by Boogertman Urban Edge + Partners

×The primary function of fibre optics in light concrete, like that produced by LUCCON or Licatron, isn't one of stability, but, rather transparency. Light concrete is manufactured in large-scale blocks from high-strength concrete, into which high-quality fibre optics in the form of weaving are introduced. Elements of differing sizes and strengths are produced by cutting the prefabricated blocks. In terms of its weather- and UV-proof characteristics, optical concrete is no different from conventional concrete.

Design Museum Triennale, Milan, 2009. Kengo Kuma's installation with Luccon light concrete

The surface of fibreglass and textile concrete is usually left unfinished, as the cement rendering is too thin and doesn't leave enough room for play. The surface of the most widely used exposed concrete can, however, be finished in many different ways: a popular way of changing the visual appearance of concrete is to skim the top layer of the concrete's mortar. This gives the concrete a more or less developed structure, a kind of relief on its surface. Secondly, the surface's texture changes, as the materials added to the concrete emerge from under this top layer. There are several possibilities here. The mason's traditional method is embossing by hand. You can finish the cement layer mechanically by sandblasting.

If parts of the surface are protected with a template, leaving others exposed to sandblasting, then you can produce patterns in this way. (See the article 'Pattern Concrete – Soft textures on a rough material'.) Depending on the grain and colour, stark contrasts are usually achieved. The interplay between these two factors – the surface texture and the three-dimensional structure – produces a variety of design possibilities, from simple façade details, through ornamentation to the depiction of a particular subject.

Treated with high-pressure water: the façade of the station car park in Aarau, made of concrete cast in-situ and coloured with mineral pigments. Schneider & Schneider Architects, photo © Heinrich Helfenstein, Zurich

Treated with high-pressure water: the façade of the station car park in Aarau, made of concrete cast in-situ and coloured with mineral pigments. Schneider & Schneider Architects, photo © Heinrich Helfenstein, Zurich

×The removal of the top cement layer can also be achieved through chemical means, with whose help patterns and other graphic subjects can be depicted. The best-known example of this technique is washed-out concrete, whose use was most popular in the 1960s and 70s for prefab building and which makes us think of those well-known washed-out-concrete plant tubs.

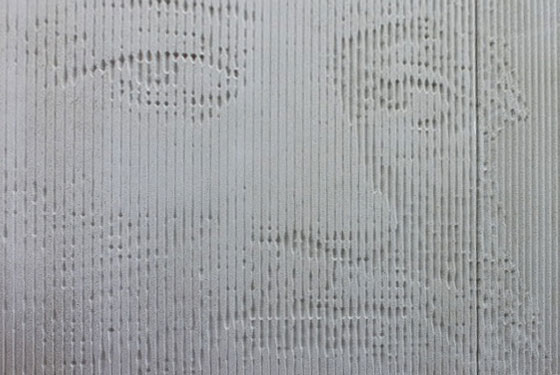

Apart from this washed-out concrete type, regarded today as highly unaesthetic, there are some very elaborate washed-out-concrete techniques on the market. The photographic concrete façade of Herzog & de Meuron's 1998 Fachhochschule Eberswalde library building, designed by photographic artist Thomas Ruff, was one of the first buildings to to use photo concrete on such a large scale. This, too, is essentially nothing more than a washed-out-concrete surface.

Using a photolithographic process, the photo is transferred onto the concrete in a screened black-and-white pattern, which is applied to a plastic film. This photo-concrete film is placed into the shuttering, where the hardening retarder on it ensures that the concrete dries out at a different rate in different places. The result is rough and smooth areas, as well as light/dark graduations. After the shuttering has been removed, the light areas of the image remain smooth, while the dark ones are cleaned out with low-pressure water.

Herzog de Meuron set another trend in architecture: the photo-concrete façade of the Fachhochschule Eberswalde's library, 1998

Herzog de Meuron set another trend in architecture: the photo-concrete façade of the Fachhochschule Eberswalde's library, 1998

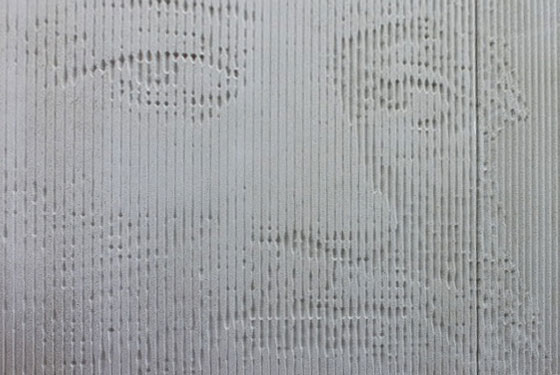

×A further means of creating photographic and other images on concrete façades is photo-engraving. A good example of this is the Gutenberghöfe project by architectural practice ap88, which was realised with the Zuber concrete factory. A picture is vectorised and, by means of a CNC shaper, applied to panel. This panel serves as template for a stencil, which is then placed into the shuttering and represents the actual form of the concrete.

Photo-concrete which uses a photo-engraving process: Zuber concrete works, with shuttering technique by Reckli. Gutenberg-Höfe, ap88 Architects

Photo-concrete which uses a photo-engraving process: Zuber concrete works, with shuttering technique by Reckli. Gutenberg-Höfe, ap88 Architects

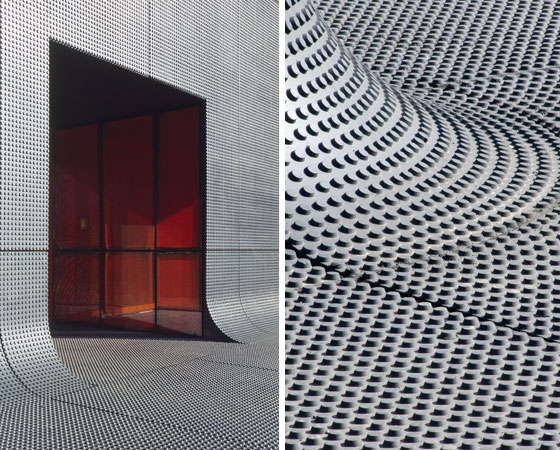

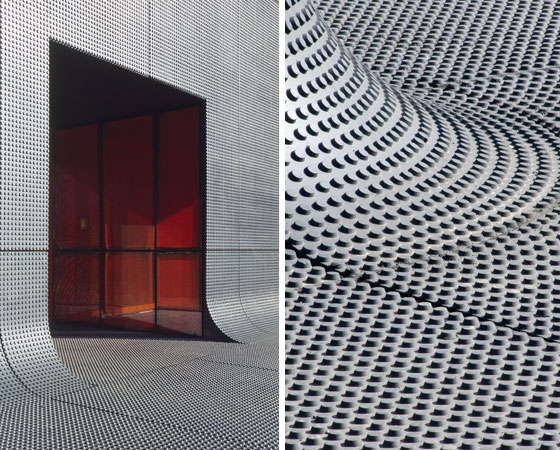

×RATP Bus Centre by ecdm architects; Photo © Benoit Fougeirol and Philippe Ruault

Apart from the know-how of the concrete suppliers, the right shuttering technique is also important: the company Reckli are specialists in the production of shuttering stencils out of silicone and polyurethane elastomers. Reckli produces, among others, photo-concrete surfaces using a vector-programme technique, a computer-aided process, which transfers image data onto plates by means of milling. Such a model serves as template for the creation of an elastic stencil, the actual mould of the photo-concrete object. The elasticity of these stencils allow them to be removed much more easily from complex forms. The stencil and concrete can be thought of in terms of dough in a baking tin. After baking, or in this case hardening, you musn't leave any material in the form.

RATP Bus Centre by ecdm architects: concrete elements into whose shuttering a 'pimply' template was placed. Photo © Benoit Fougeirol and Philippe Ruault

RATP Bus Centre by ecdm architects: concrete elements into whose shuttering a 'pimply' template was placed. Photo © Benoit Fougeirol and Philippe Ruault

×Apart from photo stencils and tailored solutions, Reckli offers a wide range of attractive standard stencils. The size of the stencils is, however, limited to a certain size, for reasons of economy. On the one hand because of the production technique, on the other due to their use on site: the concrete shuttering stencils can be reused and, therefore, are repositioned a number of times. The bigger the stencil, the heavier its weight (and the greater the amount of labour needed to move it). For large motifs, several stencils can be positioned together.

Stencils allow either surface ornamentation or highly complex vector graphics to be created, as discussed in 'The new materiality of shadows'.

The above-mentioned examples illustrate how many sides concrete has to it and how many design possibilities the material offers. The material's potential isn't something that it alone decides: it depends, too, on the innovative spirit of architects and engineers, the open-mindedness of the property owners, the know-how of the contractors and the collective will to realise something truly special.

Further projects that demonstrate the use of concrete in realising extraordinary architecture will be discussed in brief in the next installment of our concrete series.

Müther's shell constructions enjoy a cult status these days: in Soffy O.'s video 'Day of Mine', you can see the 'Kurmuschel' music pavilion in Sassnitz, the 'Inselparadies' restaurant, Rügen, and the Lifesavers' Station in Binz on the island of Rügen