Combatting water scarcity in urban environments: the Bette Intelligence Series

Brand story by Alyn Griffiths

Delbrück, Allemagne

16.11.22

In the second installment of the Bette Intelligence Series – three consecutive features sponsored by the German bathroom specialist – UNC Charlotte Dean of Arts + Architecture Brook Muller speaks about the importance of incorporating water into the design process: from bathroom fixtures to big-picture thinking from the start.

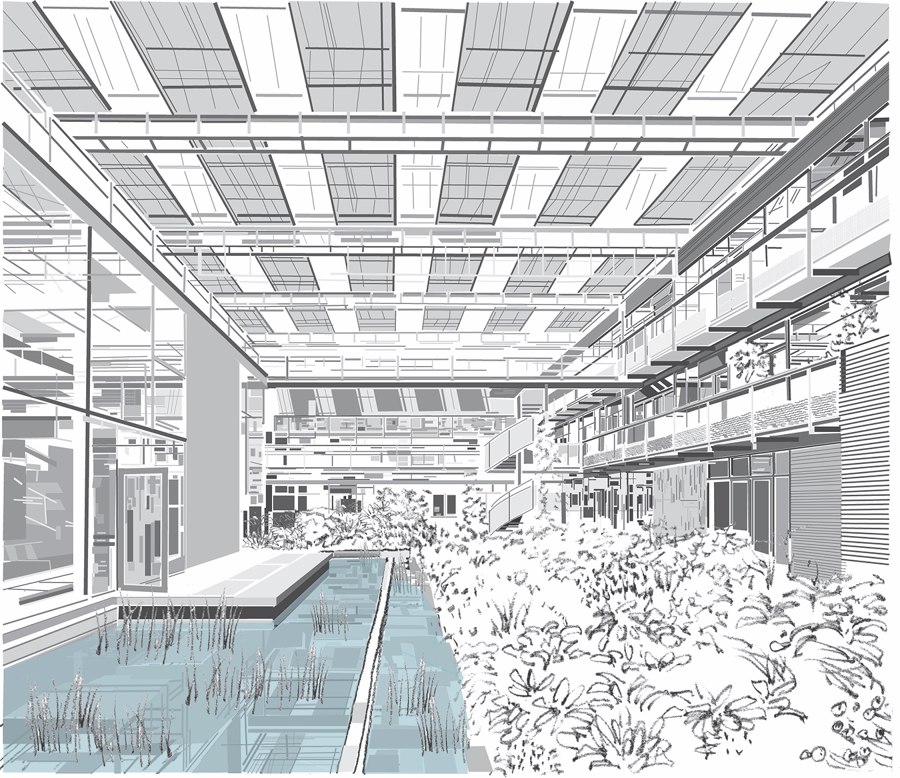

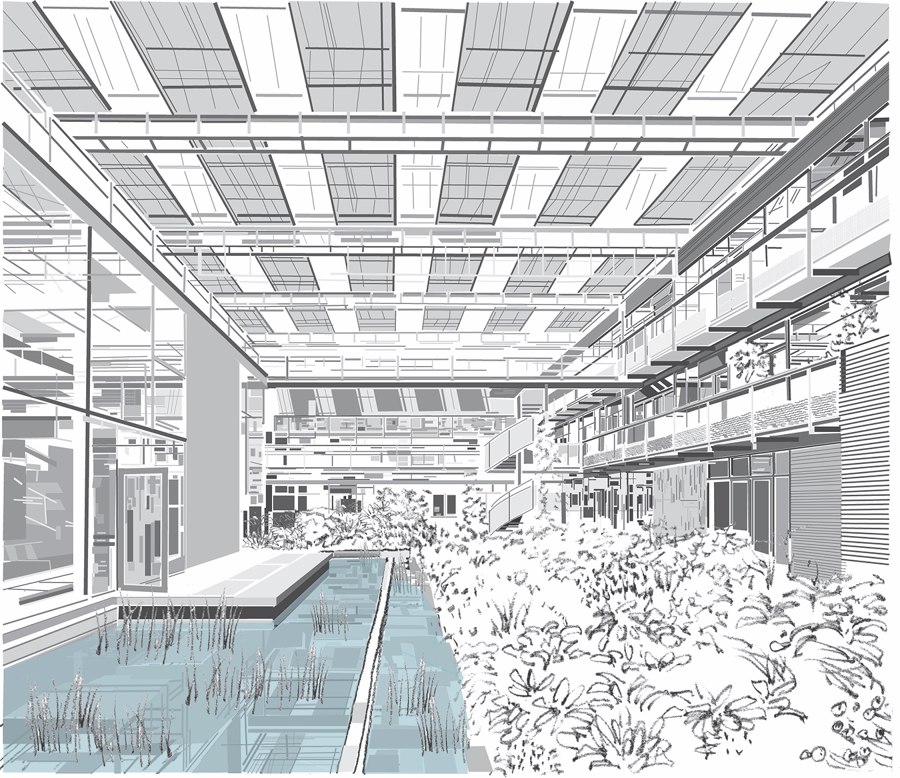

West atrium with reflecting and stormwater collection pond, IBN / Alterra Institute in Wageningen, The Netherlands, by Behnisch & Partners Architects and Michael Singer Studio (1993-1996)

West atrium with reflecting and stormwater collection pond, IBN / Alterra Institute in Wageningen, The Netherlands, by Behnisch & Partners Architects and Michael Singer Studio (1993-1996)

×Designer and academic Brook Muller has authored a book called Blue Architecture: Water, Design, and Environmental Futures that presents innovative approaches to water-centric urban design. We asked him how a “hydro-logical” approach to architecture could allow us to design cities that improve water sustainability as well as promoting more equitable distribution of our most vital resource.

Water scarcity is one of the most urgent and devastating consequences of climate change, yet it is often relegated to the sidelines of architecture and design practice. How do you suggest we change this going forward?

Every city I visit these days has a water crisis. It varies from location to location, so it might be a consequence of sea levels rising, too much water, not enough water, or the wrong kind of water in the wrong place. I'm trying to develop a design process that addresses these issues and is translatable across contexts.

When you actually bring water considerations into the creative ambit, good things happen

The prevailing attitude is that 'architects make space and engineers add water.' Accrediting professional programs in architecture in the US and Canada focus very narrowly on water – often marginalising it to plumbing or moisture transfer instead of valuing it as an integrative design medium. It’s emblematic of this not being a protagonist in the design process. This is our first point of attack. Because when you actually bring water considerations into the creative ambit, good things happen. If you make more of an effort to understand how buildings are situated within a larger hydrological context, you'll make better decisions at the project scale that could save money as well as reducing the amount of water that is wasted. It will also make buildings more connected to their site and surrounding landscape.

Brook Muller is Dean of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte College of Arts + Architecture. His research focuses on the role of the arts in urban placemaking and he has worked on water and sustainable development projects around the globe

Brook Muller is Dean of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte College of Arts + Architecture. His research focuses on the role of the arts in urban placemaking and he has worked on water and sustainable development projects around the globe

×How might architects and designers improve their understanding of how to include water sustainability in their projects?

Early in my academic career, I collaborated with a professional ecologist – we brought him into the studio process with our architecture students at a very early stage. We would write design briefs together that included rules-of-thumb for storm water run off, for habitat and for other ecological factors. These issues need to be embedded in design briefs at the very beginning of a project to ensure water systems are seen as integral to urban architecture.

Practitioners across the board would benefit greatly from taking a ‘hydro-logical’ approach to the decentralisation of urban water systems

If you don’t embed these ecological and hydrological issues into the problem statement, then architects and architecture students don’t really know how to deal with them. In essence, practitioners across the board would benefit greatly from taking a ‘hydro-logical’ approach to the decentralisation of urban water systems. This means looking at the available resources and developing distributed solutions that are far more sustainable and equitable. Instead of focusing on minimising negative impacts, we should think about how a building, neighbourhood or city can contribute in a beneficial way to larger ecological and hydrological systems.

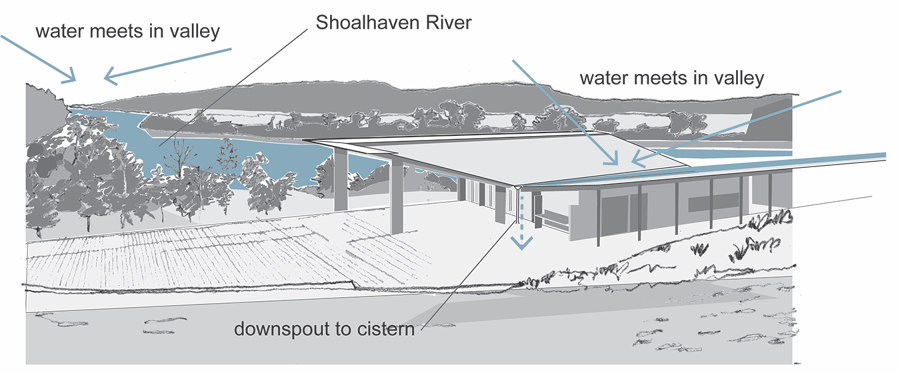

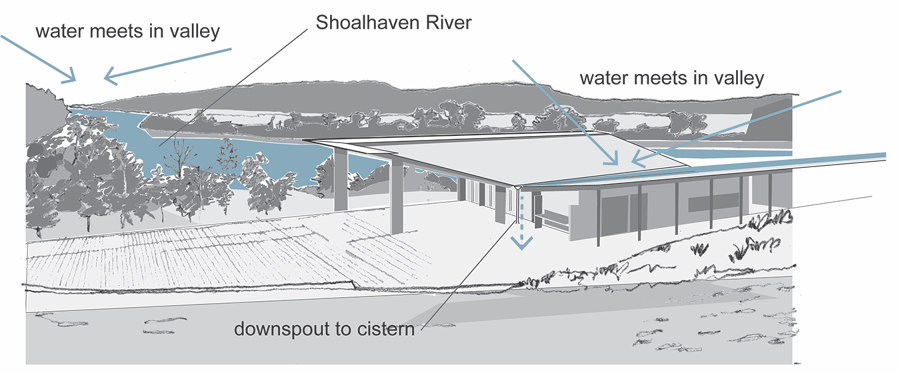

Riversdale Boyd Education Centre by Glenn Murcutt, Reg Lark and Wendy Lewin, West Cambewarra, New South Wales (1996-99): the building is a poetically hydrological analog to the landscape in which it sits

Riversdale Boyd Education Centre by Glenn Murcutt, Reg Lark and Wendy Lewin, West Cambewarra, New South Wales (1996-99): the building is a poetically hydrological analog to the landscape in which it sits

×What concrete steps can practitioners take to make sure buildings have a net-positive watershed impact?

Water schematics showing the sources, the uses and the possibilities for how water can flow through a project are very helpful. You also have to think about supply and demand. Getting harvestable sources is key. In the Pacific Northwest, for example, it rains all winter but it doesn't rain in the summer. When you look at mixed-use development and estimates of demand for a building of this type in the region, it’s almost equivalent to supply over the course of the year. But it’s asynchronous – there’s way too much water in the winter, not nearly enough in the summer.

Water schematics showing the sources, the uses and the possibilities for how water can flow through a project are very helpful

You could store that water, but it’s expensive. So you have to think about rainwater harvesting for all possible non-potable uses: seismic dampening, thermal mass, fire suppression, and then tapping into the city supply when you need to. That reduces dependence on the centralised system and allows the city to grow without overburdening the existing infrastructure.

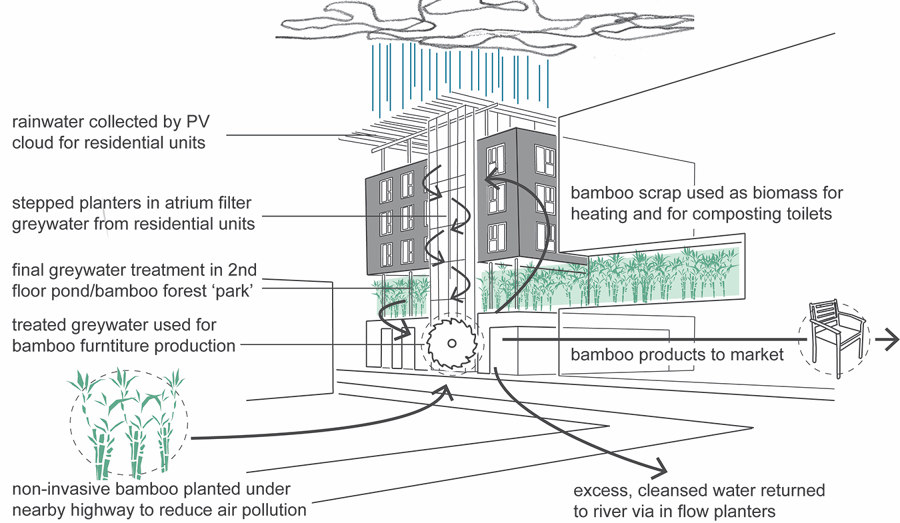

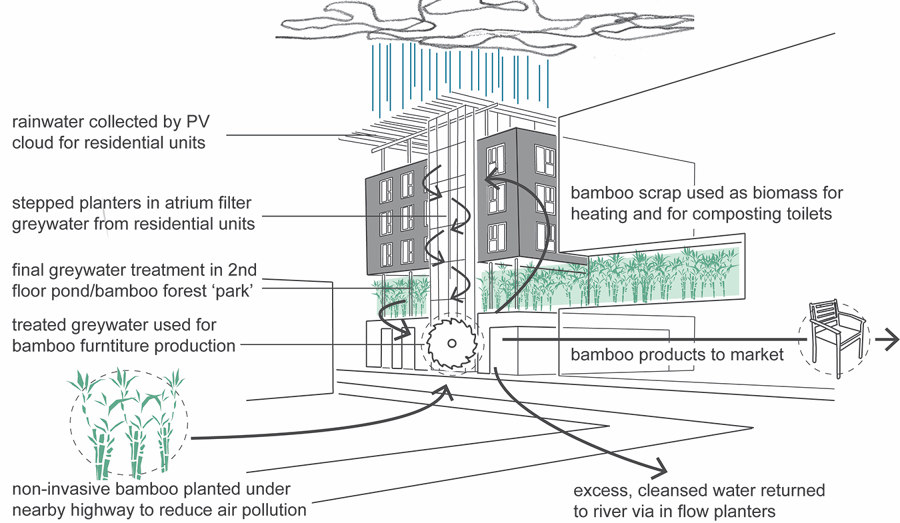

The Bamboo project (design by Joel Bohlmeyer, Amy Santimauro, and Katelynn Smith). Their 'Fabricating Wellness' scheme received a 2018 American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment AIA/COTE Top Ten for Students Prize

The Bamboo project (design by Joel Bohlmeyer, Amy Santimauro, and Katelynn Smith). Their 'Fabricating Wellness' scheme received a 2018 American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment AIA/COTE Top Ten for Students Prize

×Could you give a successful example that you've come across in your research?

There’s a project in Blue Architecture in which Hyphae Design Laboratory served as ecological design consultant – it’s a hospital in Southern California where a surgery wing was built with a green roof so recuperating patients in the room above had a view of a garden. The city required use of drought tolerant species because of the hot, arid climate, but Hyphae instead specified water loving plants and used the salty condensate from the hospital’s ventilation system as a water source. This systemic approach reused water considered to be waste as part of an architectural solution that is both attractive and economical, for a 'wet roof' significantly reduces cooling load for the interior spaces below.

Are there specific areas in design and architecture that require more attention than others?

When we look at the demand side of the equation, there are all kinds of embedded assumptions about lifestyle and cultural differences to water usage. It’s really interesting to think about the number of bathrooms a household requires, for example, and whether people are willing to live with low-flush toilets. These assumptions have implications for the kinds of fixtures we use throughout buildings, but we also need to look much more at the ecosystem in which they are situated to ensure projects are delivering a net-positive watershed impact.

It’s really interesting to think about the number of bathrooms a household requires and whether people are willing to live with low-flush toilets

We talk about form follows flows. What happens when we actually study these flows is that you find possibilities to recapture certain things, reorient and reroute in the cause of urban placemaking. Moving dollars from utilities to the landscape is another big part of it. But then suddenly these localised infrastructures are visible – that’s why we need design.

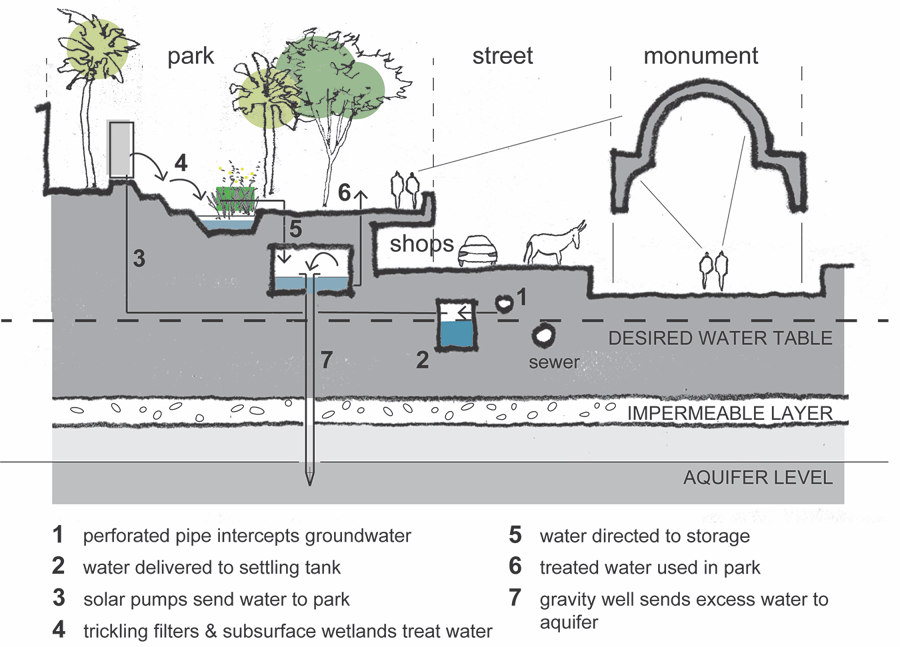

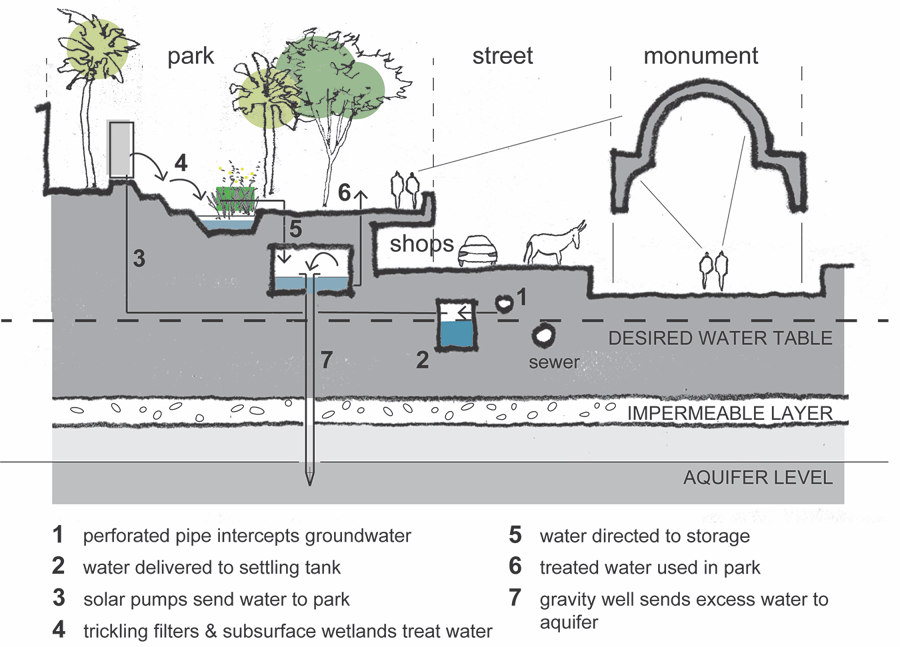

al-Khalifa Environment and Heritage Park in Cairo: water schematic involving groundwater interception and treatment (based on a drawing by student participants in the International Groundwater School)

al-Khalifa Environment and Heritage Park in Cairo: water schematic involving groundwater interception and treatment (based on a drawing by student participants in the International Groundwater School)

×Water scarcity is intimately connected to socioeconomic status and different localised attitudes towards the built and natural environments. What solutions do you propose to bridge some of the inequalities that currently exist?

People in the water industry say we’re at a stage now that’s similar to what was happening with energy a generation ago. A revolution is underway, price points are reducing and that means as designers and architects, we should be gearing up to make change happen. For me, it’s about how to take the waste and have it become the resource to make a new system go. I like the idea of co-opting failed modernist systems in the cause of localised solutions to support people who don’t have high quality open space.

People in the water industry say we’re at a stage now that’s similar to what was happening with energy a generation ago

For countries in the Global South where there’s not a lot of money for infrastructure investment, too many people are living without piped water. The methods being used to bring water into rapidly expanding informal settlements are also contributing to the spread of diseases. Spontaneously dug wells adjacent to existing cesspits dramatically increase the risk of malaria and dengue transmission, for example. I think rainwater harvesting could be a better way to supply clean water at a household or district scale, but it needs to be managed properly to minimise the risk from infections.

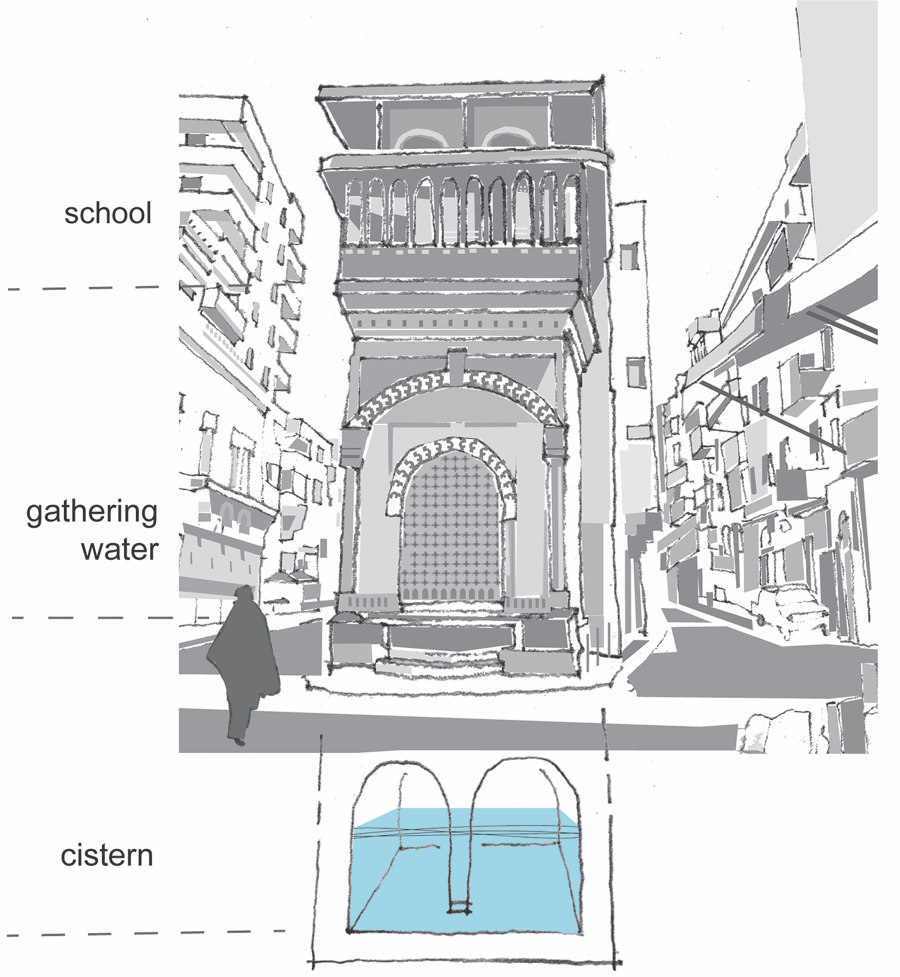

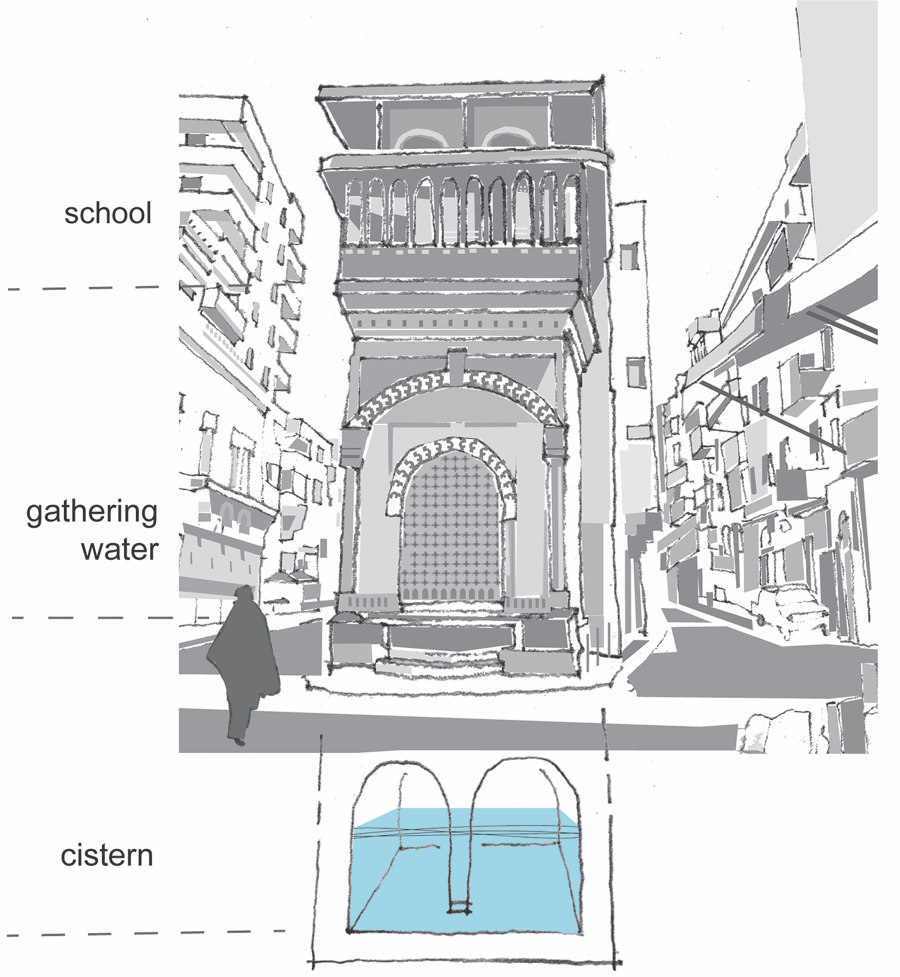

Sabil-kuttab of Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in Cairo (1744), from the mid eighteenth-century Ottoman period. A school or kuttab sits atop a public space for gathering water that in turn sits atop cisterns

Sabil-kuttab of Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in Cairo (1744), from the mid eighteenth-century Ottoman period. A school or kuttab sits atop a public space for gathering water that in turn sits atop cisterns

×Your book closes by asking designers about the future of water systems and what environmental legacies they’d like to leave behind. What stood out to you?

I see a generation that wants to change the world because they perceive these existential threats and want to figure out how to do something about them. I think there’s tremendous receptivity and a great chance to empower people with knowledge. I believe a more modest approach is ultimately more ambitious in trying to reconnect our settlements with hydrological and natural systems.

If we take water seriously, we can transform cities relatively inexpensively in ways that would support our environmental goals and our desire to live in urban environments that are comfortable and supportive of all their inhabitants

If we think about systems and take water seriously, we can transform cities relatively inexpensively in ways that would support our environmental justice goals, our climate change resilience goals and our desire to live in urban environments that are comfortable and supportive of all their inhabitants. There is an ethical imperative to think about the transformation of urban environments, climate change impacts, water scarcity, rapid urbanisation, we have to rise to those tensions.

© Architonic

Head to the Architonic Magazine for more insights on the latest products, trends and practices in architecture and design.