Back to the future: 100 years of the Bauhaus

Texte par Dominic Lutyens

London, Royaume-Uni

13.03.19

The game-changing phenomenon that was the Bauhaus is still very much present in our built and material environment. Amid the centenary celebrations, we take an objective look at its significance.

Students of the Bauhaus in Dessau. Photo: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

This year sees the centenary of the opening of the Bauhaus, widely considered the most influential art and design school of the 20th century. In the wake of World War I, the Bauhaus, founded by architect Walter Gropius in 1919 in Weimar, Germany, believed in unifying all the arts and crafts.

Its uncompromising espousal of modernity saw it reject artistic tradition and any sentimental attachment to it. It also allied itself with such democratic principles as housing and good, functional design available to all.

To many, the Bauhaus became synonymous with modernism and anyone sympathetic to the school respects its commitment to artistic experimentation. Its teachers included key avant-garde cultural figures – Gunta Stölzl, Paul Klee, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe and László Moholy-Nagy, to name a few.

It’s little surprise, then, that this anniversary is being celebrated worldwide via a raft of exhibitions and the opening of the new Bauhaus Museum Dessau later this year, designed by architects Gonzalez Hinz Zabala.

Top: The Walter Gropius-designed main building at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Above: Throughly modern, cantilevered Bauhaus balconies. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

Top: The Walter Gropius-designed main building at the Bauhaus, Dessau. Above: Throughly modern, cantilevered Bauhaus balconies. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

×Although widely associated with functionalism, the Bauhaus was built on a complex, contradictory set of values. At its inception, it was primarily influenced by the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement and the ideals of William Morris. At the Weimar site, the school placed an emphasis on craft and self-expression. A dominant figure was Expressionist painter Johannes Itten, who headed up its six-month foundation course, dedicated to exploring materials and form, and was interested in meditation and psychoanalysis.

But from the early 1920s, Gropius steered the school’s ethos towards mass production, leading to Itten’s resignation. Gropius designed its new school at Dessau, whose streamlined form embodied the ideals of the machine age, which the Bauhaus, in its second iteration, idolised. After briefly moving to Berlin in 1932, the beleaguered Bauhaus closed down under pressure from the Nazi regime, which viewed it as a refuge for Jewish-Marxist creatives, although many of its former teachers and alumni travelled the world disseminating Bauhaus ideals.

Top: Gropius's Masters' Houses at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Above: The new Master's Houses, designed by Bruno Fioretti Marquez Architekten. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

Top: Gropius's Masters' Houses at the Bauhaus in Dessau. Above: The new Master's Houses, designed by Bruno Fioretti Marquez Architekten. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

×Architecture was seen as the zenith of cultural activities, though its architecture department didn’t open until 1927.

Of course, the creeping postmodernist movement, which has its roots in the 1950s, questioned the precepts of modernism – in architecture, philosophy and literary criticism – which some have perceived as legitimising totalitarianism. In his 1981 book From Bauhaus to Our House, Tom Wolfe derided the one-size-fits-all delusions of International Style architecture, for example modelling the design of a school on workers’ housing. “As for the honest sculptural objects designed for worker-housing interiors, such as Mies’s and Breuer’s chairs, the proles ignored them or held them in contempt because they were patently uncomfortable,” he wrote.

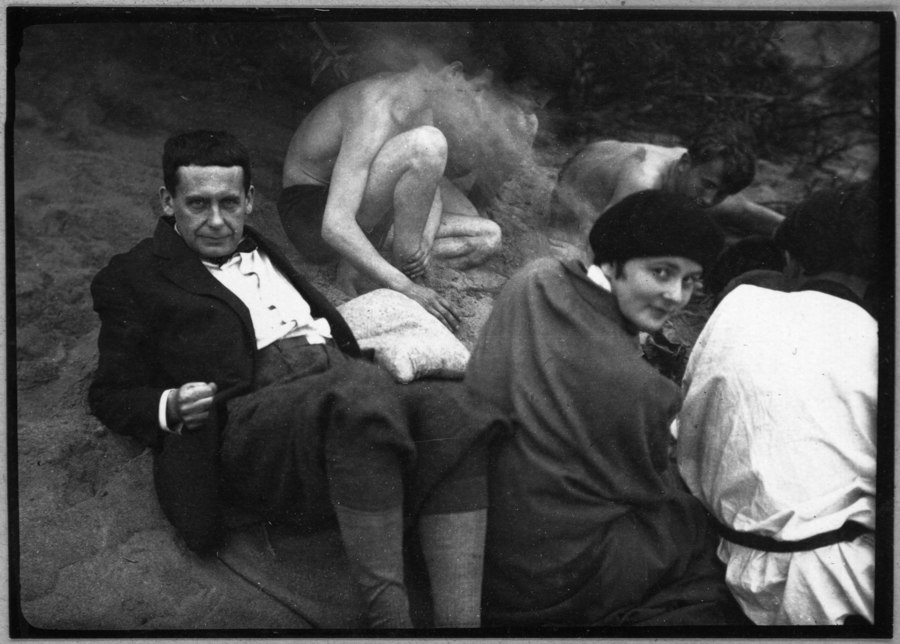

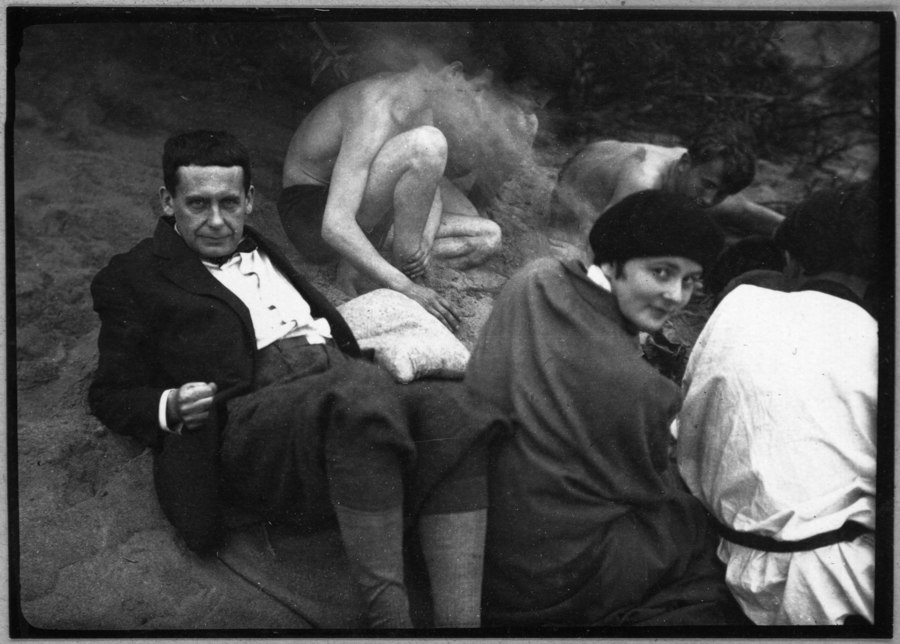

Top: Bauhaus director Walter Gropius, and wife Ise. Above: Marcel Breuer and students. Photos: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

Top: Bauhaus director Walter Gropius, and wife Ise. Above: Marcel Breuer and students. Photos: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

×Ironically, while the centenary celebrations demonstrate the high esteem in which the Bauhaus is held, the once-sacrosanct school has attracted criticism for not living up to its socially progressive reputation.

True, social housing designed by the Bauhaus, exhibited in Stuttgart at the Die Wohnung exhibition in 1927, included flats for single, professional women. But the patriarchal Gropius restricted the number of women admitted to the school and tried to confine them to practising crafts that he deemed feminine, such as weaving, as the recent show on Anni Albers at Tate Modern, London, highlighted.

Top: The Weisse Stadt in Berlin, designed by architects Martin Wagner, Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, Bruno Ahrends and Wilhelm Büning. Above: one of the houses by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret at the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

Top: The Weisse Stadt in Berlin, designed by architects Martin Wagner, Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, Bruno Ahrends and Wilhelm Büning. Above: one of the houses by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret at the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

×According to Alan Powers, author of new book Bauhaus Goes West: Modern Art and Design in Britain and America, the Bauhaus’s fame rests partly on Gropius’s talent for promoting it rather than for its ability to put theory into practice. “There were many other avant-garde German design schools at the time, but the Bauhaus members were good self-publicists. Even its snappy name was a stroke of genius. But the idea that the Bauhaus created prototypes for designs that were commercially successful is a myth. They only made luxury, elitist objects. That said, the quality of weaving and graphic design was good.”

Another fallacy, according to Powers, is the idea that the Bauhaus spawned mass social housing. Its adoration of technology for its own sake also now seems outdated. Its buildings were often oriented towards the sun – now one of the core principles of the Passive House standard practised in architecture – but this was based on the ill-founded belief that sunlight killed germs rather than for pioneering environmentalist reasons: “The Bauhaus can’t take credit for these ideas, which were very general at the time,” says Powers.

When Powers made a visit to Gropius’s house in Lincoln, Massachusetts, in the late 1970s to meet his widow Ise, she stressed the way that the south-facing windows were shaded in summer by an overhang but allowed winter sun to come in, claiming this contributed to warming the rooms. Yet, in Powers’ view, the Bauhaus houses at Dessau weren’t as idyllic, describing them as “dismal” and “tightly packed together”.

But for all the criticism levelled at the Bauhaus, many of its designs, including Marianne Brandt’s lighting, Breuer’s chairs, Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s glassware and Albers’ rugs, are coveted today, and its spare aesthetic, which has influenced everything from furniture to typography, still looks modern and relevant.

Top: The Bauhaus's original home in Weimar, designed by Henry van de Velde. Above: Berlin's Bauhaus Archiv, completed in the 1970s and designed by Gropius together with Alex Cvijanovic, Hans Bandel. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

Top: The Bauhaus's original home in Weimar, designed by Henry van de Velde. Above: Berlin's Bauhaus Archiv, completed in the 1970s and designed by Gropius together with Alex Cvijanovic, Hans Bandel. Photos: Tillmann Franzen

ש Architonic