Creating an Urban Splash

Texte par Dominic Lutyens

London, Royaume-Uni

29.07.14

Architects of urban projects are increasingly in thrall to water, believing it benefits them in a number of ways — from the aesthetic to the psychological. In one sense, when reflected in water, buildings look larger and more imposing. Yet water’s evanescent, organic qualities can also soften and appear to dematerialise their severe lines, even making them look ethereal.

The five restaurant buildings at Hassell’s Palm Island project in Chongqing, China, which glow glamorously at night. Their organic shapes complement the lagoons and ‘water courtyard’ they front

The five restaurant buildings at Hassell’s Palm Island project in Chongqing, China, which glow glamorously at night. Their organic shapes complement the lagoons and ‘water courtyard’ they front

×The hulking volume of London’s concrete, brutalist Barbican Centre is leavened by its lushly planted lakes, while Louis Khan’s monolithic National Parliament House in Dhaka, Bangladesh, whose construction began in 1961, looks almost dreamlike when viewed across the artificial lake beside it. This autumn sees the opening of Frank Gehry’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, an art gallery with a sail-like, glass structure that will seem to float above a water garden.

Water in cities is often equated with nature. Like vegetation, it offers urbanites a soothing antidote to stressful city living. Water is also used to complement architecture with an organic aesthetic — take Santiago Calatrava’s 1998 City of Arts and Sciences building complex in Valencia, Spain. One of Japanese starchitect Tadao Ando’s key concerns is to fuse architecture and nature, indoors and out, and his glass-fronted design for the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, creates the impression of forming a seamless whole with the 1.5-acre pond it emerges from. Here, Andao has exploited glass’s visual similarity to water.

Chongqing is one of China’s hottest, most humid cities in summer, but at Palm Island breezes blowing over the water and its buildings’ reflective facades help to reduce temperatures

Chongqing is one of China’s hottest, most humid cities in summer, but at Palm Island breezes blowing over the water and its buildings’ reflective facades help to reduce temperatures

×One particularly extensive use of water can be found at Australian architect Hassell’s, Palm Island project, in China. On the banks of the Qingnian Reservoir in Chongqing and Palm Spring Geological Park Lake, Palm Island comprises five curvilinear restaurant buildings that appear to float on the water like islands in an archipelago. Customers can enjoy views of the lagoons and a circular ‘water courtyard’ with an infinity pool-style border. By day, the buildings — fronted by glass and white ceramic rods — catch the sunlight as it dances on the water; by night, their glamorous reflections can be seen in it, thanks to lights incorporated into their facades.

Hassell also secreted the restaurants’ service zones beneath the waterline to ensure that views of the water are uninterrupted, further proof of the central role it plays here. Aesthetics aside, the water also performs a practical and environmentally friendly function: the buildings’ reflective facades and breezes blowing across the water reduce temperatures and energy use, while harvested and recycled water replenishes the lakes.

OMA’s surreal runway for Prada’s spring/summer 2015 menswear collection in Milan last June paired a stylised, sapphire-blue pool and a carpeted catwalk in a subterranean, industrial space

OMA’s surreal runway for Prada’s spring/summer 2015 menswear collection in Milan last June paired a stylised, sapphire-blue pool and a carpeted catwalk in a subterranean, industrial space

×According to its project leader Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, OMA’s unusual intervention ‘questions the relationship between outdoors and indoors: water invades the space, changing its proportions and reflecting unexpected points of view’

According to its project leader Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, OMA’s unusual intervention ‘questions the relationship between outdoors and indoors: water invades the space, changing its proportions and reflecting unexpected points of view’

×Contemporary architecture’s affection for the aqueous was also in evidence at Prada’s spring/ summer 2015 menswear runway show, held in Milan in June. Rem Koolhaas’s studio OMA, which collaborates regularly with Prada – it has, for example, created a portable pavilion to showcase the Italian label’s cultural projects – took an industrial, subterranean space and magicked it into a pool of sapphire-blue water and a rectangular catwalk that appeared to hover above it. OMA describes the surreal environment as somewhere ‘between a cave, cruise ship and indoor pool’. While most architects embrace water for its natural qualities, OMA did the opposite, marshalling it into an ultra-artificial, coldly static surface.

French studio TVK’s radical remodelling of Paris’s Place de la République has vastly enlarged the square and includes a popular, shallow pool that epitomises today’s trend towards understated, urban water features

French studio TVK’s radical remodelling of Paris’s Place de la République has vastly enlarged the square and includes a popular, shallow pool that epitomises today’s trend towards understated, urban water features

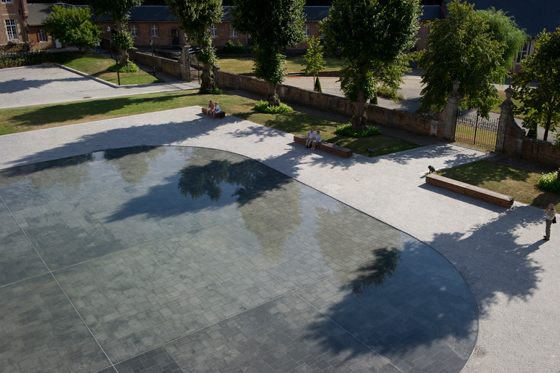

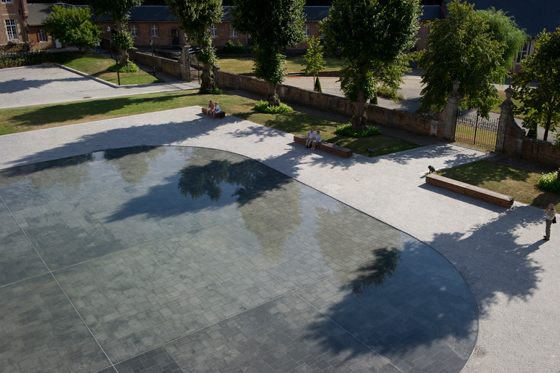

×A more common trend is to use water to make subtle interventions in urban architecture. When shallow and transparent, water lends itself well to this approach, as demonstrated by French practice TVK’s redesign of Paris’s Place de la République. Compared with its decision to enlarge the square by making the surrounding roads narrower, such that it’s now the city’s largest pedestrian area, the addition of a shallow reflective pool – which forms an elegantly continuous line with an adjoining glass-fronted café – is a highly minimal intervention. The project, which also boasts 150 new trees, embodies another strand of the trend towards featuring water in cities – the creation of an urban oasis.

OMGEVING’s similarly serene water feature, which fronts Averbode Abbey near Diest, Belgium, serves another purpose typical of contemporary, urban water features — reflecting architecture, in this case the baroque abbey

OMGEVING’s similarly serene water feature, which fronts Averbode Abbey near Diest, Belgium, serves another purpose typical of contemporary, urban water features — reflecting architecture, in this case the baroque abbey

×Belgian architects OMGEVING’s shallow pond in the courtyard of the 17th-century Averbode Abbey near Diest, in Belgium, is similarly restrained, though the main focus here is on the water. Its serene, limpid film of water – which forms a simple, organic shape with rounded corners and no obvious border — acts as a neutral foil to the baroque architecture of the church reflected in it. Like TVK’s pool, the water here is shallow enough for people to paddle in.

Westpol’s quirky observation deck in the centre of a lake, reached by a ramp, sees the city almost submerged by nature, with visitors surrounded by reflective water and lush woodland

Westpol’s quirky observation deck in the centre of a lake, reached by a ramp, sees the city almost submerged by nature, with visitors surrounded by reflective water and lush woodland

×Seemingly more immersive is Swiss practice Westpol’s idiosyncratic observation deck in Vöcklabruck, Austria. This sees visitors literally walk into a lake via a ramp flanked by walls that leads to a circular observation deck with a wraparound bench designed for contemplating the water and woodland. It’s strikingly reminiscent of 20:50, artist Richard Wilson’s legendary, similarly structured installation of 1987. But while this contains pitch-black engine oil to menacing effect, Westpol’s project is idyllically pastoral.

Surrounding trees in Mayfair, London, this water feature by Tadao Ando and Blair Associates creates an urban oasis. It also periodically sprays clouds of misty water to arrestingly atmospheric effect

Surrounding trees in Mayfair, London, this water feature by Tadao Ando and Blair Associates creates an urban oasis. It also periodically sprays clouds of misty water to arrestingly atmospheric effect

×True to form, Tadao Ando, in collaboration with London practice Blair Associates, recently designed a truly original water feature that evokes nature right in the centre of London: Mayfair. Part of the Grosvenor estate’s £10m programme to upgrade some of its streets in Mayfair and Belgravia, it consists of a water-filled basin encircling trees in front of The Connaught hotel. Around the base of these are atomisers that spray clouds of water for 15 seconds every 15 minutes, blurring the straight edges of nearby buildings and diffusing strong sunlight. At night, fibre-optic lights below the water’s surface illuminate the trees.

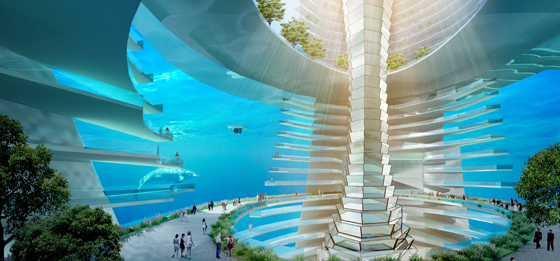

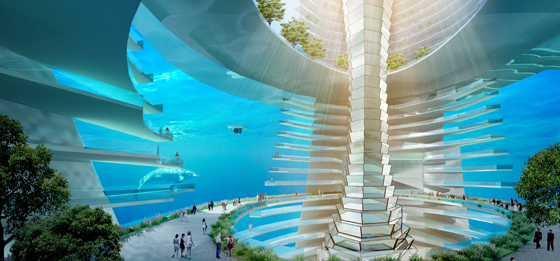

More profoundly, environmentalist concerns about the planet’s dwindling natural resources are inspiring some radically futuristic architectural concepts involving not just relatively small water features but swathes of the sea. Take AT Design Office’s Floating City — a hypothetical solution to our planet becoming so built-up that cities might need to be constructed on our oceans. Arguably, this is questionable. ‘Population pressures make the idea of floating cities attractive,’ says Tony McCormick, a principal at Hassell. ‘But the organisms in our oceans are under great pressure from human activity, and do not need to deal additionally with the impact of floating cities. Instead, we should create more environmentally friendly cities on land.’

AT Design Office’s ultra-futuristic concept for a Floating City, an energy-efficient, sustainable metropolis on a 10-sq-km island dreamt up as an alternative to destroying the earth’s countryside

AT Design Office’s ultra-futuristic concept for a Floating City, an energy-efficient, sustainable metropolis on a 10-sq-km island dreamt up as an alternative to destroying the earth’s countryside

×Yet Floating City, commissioned by Chinese construction firm CCCC-FHDI, is both undeniably inventive and, says its architect Slavomir Siska, ‘energy-efficient and self-sufficient’. It proposes a 10-sq-km floating island that would extend beneath the sea. Made of interlocking, prefabricated modules, it would be assembled on a real island, then floated to the site and connected. Transport would be provided by electric vehicles on the island and, beneath it, by submarines. Farms on the island would cultivate food, and rubbish would be disposed of in a recycling centre. This fantasy is also appealingly retro-futuristic, recalling the theoretical Plug-In City – devised by the 1960s’ avant-garde architects Archigram – which envisioned modular, residential units that could ‘plug in’ to a larger infrastructure.

For now, though, the approach to designing urban water features is considerably more low-tech but is still making waves.