Smallest rooms that provoke the loudest protests: Laufen bathrooms

Texte par LAUFEN BATHROOMS

Laufen, Suisse

26.07.21

Is it time to rethink the public bathroom for the 21st century?

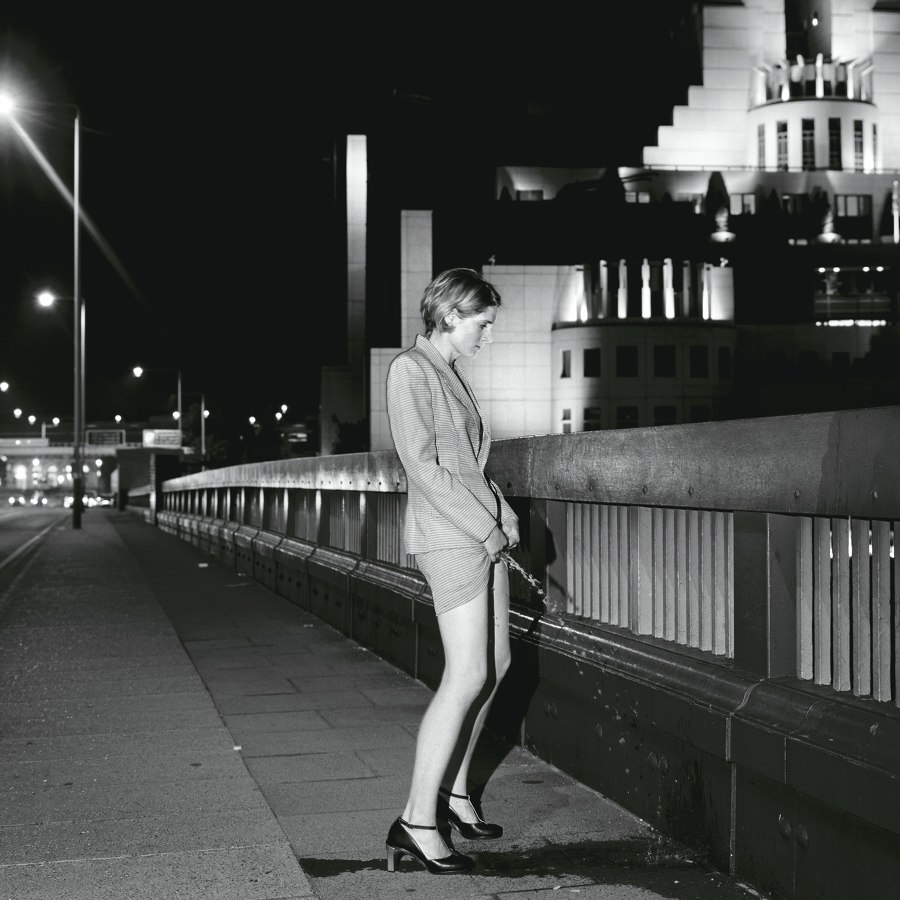

Vauxhall Bridge, Old Street, Silvertown, 1995. Photo: Sophy Rickett

‘Cacator cave malum! Aut si contempseris, habeas Jovem iratum.’ ‘Beware of defecating in the street! Otherwise, Jupiter's wrath will descend upon you!’ This dire warning, found on the wall of a house in Pompeii, was probably inscribed by a latrine lessee with a keen sense of the benefits of advertising. Excreta were quite a lucrative business in the Roman Empire. While the rural population could relieve themselves in the open air, this particular practice had to be avoided in the cities. Around 400 AD, in Rome alone, 144 latrines with moats to provide flushing afforded relief for well over fifty people at a time: some of these establishments were distinctly luxurious, adorned with columns and mosaics, and equipped with underfloor heating. These were venues where people met for chit-chat and networking while quite literally 'doing their business'. Also, these lavatories were supposedly age- and gender-neutral: men, women and children sat side by side in harmony while releasing both solid and fluid discharges. Less affluent clients would visit the simpler necessarias –the Roman metropolis boasted 254 of them at that time – or could avail themselves of pissoirs fitted with urine pots which, once full, were taken away by urine collectors. Urine was the 'Persil of ancient Rome', because its ammonia content could loosen the dirt from clothes. A shining example of the circular economy!

Toilet to-go

‘Public and toilet do not sit well together ... The toilet is a foundational start point where each of us deals directly with our bodies and confronts whatever it provides, on a schedule not of our own making.’

Harvey Molotch in 'Toilet – Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing Edited', 2010

Over the past three decades, the number of public toilets available in cities has been constantly dwindling, whereas their bad reputation has continued to grow

As we know, the development of civilisation is not necessarily a process of optimisation. In mediaeval France, a government decree required people to yell out 'Gardez l'eau!' (Watch out for water!) three times before tipping their chamber pots out of the window. For centuries, people simply responded to nature's call – and disposed of the results – in the streets of Europe's cities. The concept of 'public toilet' was thus enhanced by an olfactory and hygienic dimension that entailed fatal consequences for public health.

If the loo is not in situ where you happen to be, you simply take it with you. In the 18th and 19th centuries, women had recourse to a 'to-go' mug for nocturnal use: this was the 'bourdalou', which bore some resemblance to a gravy boat. A similar mobile toilet including 'personal service' was offered by the 'ladies and gentlemen of the privy' ('Buttenweiber' and 'Buttenmänner') in mid-19th century Vienna: ‘Who wants to spend a penny? Who would like to poop in my comfort station for a kreuzer?’ they would call out to their needy clientele in the city's busy squares and parks. Hidden (to a degree) behind the coats of these professional excretion facilitators, women and men were able to relieve themselves. However, demand exceeded supply and the fad did not catch on.

François Boucher - "La Toilette intime", about 1760

For a long time, there were virtually no toilets for female users in public spaces – either in educational institutions, recreational facilities, or even (in their earliest days) in factories. Since these settings were not intended for women anyway, the absence of lavatories for them was the logical consequence – or was it, rather, the other way around? Gender research coins the term 'silent discrimination' for this phenomenon. At the dawn of the 20th century, the women's rights activists of the suffragette movement put a stop to the situation by campaigning – successfully – in favour of pissoirs for women. So: there is a socio-political dimension to the toilet issue.

The business of doing one's business

‘The public convenience is a place where boundaries are crossed: boundaries between the individual and the general population, and between what is private and what is public. The convenience is functional and sterile. And once you're inside, you want to get out again as quickly as possible.’

Christa Hager, Austrian historian and journalist

Over the past three decades, the number of public toilets available in cities has been constantly dwindling, whereas their bad reputation has continued to grow: they are seen as filthy and unhygienic, and as places where homeless people, drug addicts and prostitutes meet up. Private operators charge between 50 cents and one euro for their services – a fee, incidentally, that is only levied for the use of the ladies' toilets in many cases, while the men are granted free passage; this has not improved the situation and has done nothing to foster gender equality. Whether Starbucks and McDonalds were forced into entering the toilet business against their will is debatable. If everyone with a really urgent need to "visit the smallest room" orders a tea latte and a burger to get the code, then the practice will ultimately pay off for the company. Incontinence is a taboo subject. There are people – especially those more advanced in years – who are afraid of not reaching a toilet in the nick of time when the need is pressing, so they prefer to stay at home or regularly drink too little; it is hard to gauge their exact number, but it is certainly large.

Laila Olvedi from Berlin designed the Missoir – a squatting urinal for women with no water consumption

In 2002, the German town of Aalen in Baden-Württemberg came up with a simple but ingenious idea: the 'Nice Toilet' (or 'Lovely Loo'). Innkeepers and shop owners make their toilets available free of charge and receive compensation from the public sector for their efforts and expense. A red sticker signals participation in the scheme, and also indicates whether a nappy-changing table or a disabled WC is available. Hundreds of German municipalities have already joined the project, and now there is even an app that shows where the nearest 'Lovely Loo' can be found wherever one happens to be.

The 'Nice Toilet'

Designing a public toilet can be a challenging construction project – a point that is borne out by the 'Tokyo Toilet Project', for which the crème de la crème of the Japanese architectural world was engaged in the run-up to the 2020 Olympic Games: among them, none other than Pritzer Prize winners Toyo Ito, Shigeru Ban, Tadao Ando and Fumihiko Maki.

The public toilet cubicle designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban hit the headlines around the world and captured much attention on social media. This apparently exhibitionistic, colourfully lit, transparent facility allows everyone a voyeuristic view into an intimate space that is normally hidden. But the cubicle conceals a 'magic trick': the special glass turns opaque as soon as the door is locked – so users can enjoy the privacy and security of an ordinary toilet while the light continues to flood in.

The Missoir, a urinal for women developed by Laila Olvedi of Berlin

Urinals for women have long been a focus of the work of German industrial designer Bettina Möllring. She views the long-established design of public toilets as essentially ancient. ‘In the meantime, nothing has been happening. These are important places where we undress, where we become defenceless. So that increases our need to feel safe and secure.’

Goodbye to queues!

‘Guys only need to be covered from the front, but women need to be covered from both front and back,’ says the young Copenhagen-based architect Gina Périer. Together with her colleague Alexander Egebjerg, she has designed the Lapee, a pink plastic urinal for women – you could call it a 'Portaloo 2.0' – for use at festivals and outdoor events. The Lapee can be produced industrially; it is robust, easy to transport and simple to clean: a toilet without doors that allows women to urinate quickly and safely, squatting in a slightly elevated position so they can keep their eyes on the surrounding area without others looking in. While urinating, the woman is at the same height as a standing person – intimate, but not too intimate. In conventional mobile restrooms, it apparently takes an average of three minutes to accomplish one's business; according to the architects, Lapee slashes the time to a mere 30 seconds. So it's goodbye to queues!

‘The gender inequality in accessing toilets in cities is widely invisible and it is so normalised that it’s simply not questioned and mostly ignored‘ Social Designerin Elisa Otañez

Waiting in line for the ladies' loo, even though pressure on the bladder is mounting: eliminating this trying experience was also the goal of Laila Olvedi from Berlin when she designed the Missoir, a urinal for women. Missoir is a squatting urinal for women with no water consumption. Three grids are recessed into its floor, and women urinate in a squatting position while holding on to bars at the side if necessary. Like in men’s public toilets, there are no doors and female urinators have direct access. ‘Even better than peeing behind a bush!’

Ladies, gentlemen, disabled? Choose, please!

‘Butch women are often hounded out of women's toilets, gender-neutral people have no safe place to pee, and there is discrimination against trans women who don't enjoy the privilege of an established urinary routine.’

Justin Adkins, Trans Activist

Antje Mayer-Salvi, founder, CEO and Editor in Chief of C/O Vienna Magazine

The provision of separate public toilets is largely based on an outdated gender concept that excludes trans identities: this leads to stressful situations for transgender individuals that quite frequently involve insults and threats of violence if they choose the supposedly 'wrong' door. Other facts, too, show that the concept for public toilets needs a rethink: nappy-changing tables are still mainly to be found in women's toilets, and there are virtually no conveniences where women can wash their hands inside the cubicle before and after changing menstrual hygiene products without touching the door handle – so it becomes impossible to rinse out a menstrual cup, for example.

The German working group on trans*emancipatory university politics (AG trans*emanzipatorische Hochschulpolitik) has proposed a simple and exciting experiment: label toilets according to their function. The signs simply state whether there are urinals, sit-down toilets or only sit-down toilets in the room: 'All genders are welcome!'

Text: Antje Mayer-Salvi

In memory of Sabina Durdik

© Architonic