"Reduction is the key word"

Texte par Nora Schmidt

Berlin, Allemagne

28.08.09

Meanwhile osko+deichman have impressed a number of prestigious manufacturers with their reduced and minimalist designs. We met them at their studio in Berlin.

The two German designers Blasius Osko and Oliver Deichmann have been working as a team for over ten years now. They first attracted international attention with their 'Pebble' sofa at Salone Satellite in 2005. A lot has happened since then. 'Pebble' is finally in production and osko+deichman have impressed a number of prestigious manufacturers with their reduced and minimalist designs. We met them at their studio in Berlin.

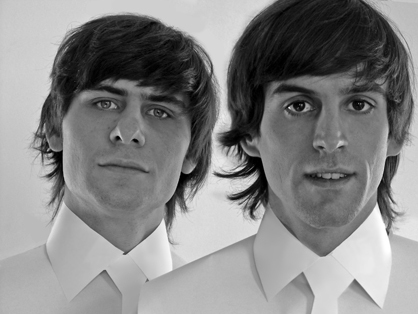

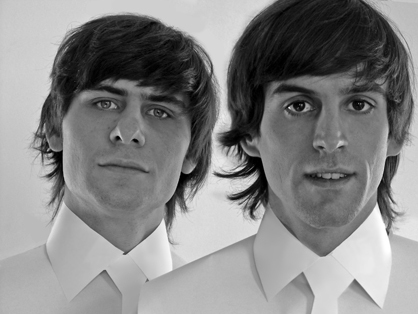

'Pebble' armchair by osko+deichmann for Blå Station

You got to know each other while you were studying in Berlin and started your first company as early as 1998. How did this early cooperation come about?

Deichmann: Yes, everything actually started during an integrative course of study which was taking place in this form for the last time. We worked very hard in a group of 10 students. As soon as we received our preliminary diploma we decided to set up our own company -- in the late 90s there was a feeling that everything was possible and in this spirit we launched 'Wunschforscher'.

Osko: during the period of the New Economy everything was very dynamic and you could take risks.

Last year you started a cooperation with the Swedish manufacturer Blå Station. Your 'Pebble' sofa, which you presented in 2005 at the Salone Satellite, is now finally in production. It was actually ready for production back then -- why was it mothballed for so long?

In fact it wasn't mothballed for so long, at least not by us but rather by a number of manufacturers. The original response to the sofa was great and a number of prestigious companies were interested in it. However, the first manufacturer we came to an agreement with simply took too long for us, and the next one withdrew from the project – I no longer know how many hands 'Pebble' went through. Blå Station got in touch with us almost 4 years after they had seen the sofa in Milan.

Since you have been receiving regular commissions, including some from major producers, has anything changed in the way you work? Has your success had an effect on the design process?

Deichmann: Not really, we try as much as possible to retain our playful approach. In addition we have always been able to work well under pressure. However, it has to be said that the depth of our work may have changed in some way. In the past there was simply more time to let the project rest for a while, before returning to it a few weeks later. We now have to make progress at a faster pace.

In your work do you always have a typical customer in mind, for example an architect?

The application of a product in relation to its architectural setting is of course important and this is very much part of our work, although it tends to come at the end of the design process rather than the beginning. However, we avoid complying with concrete specifications, even those of an architect. The product arises from an initial idea and then develops on the basis of our own creative operations. The preferences and wishes which we want to fulfill with our product are important to us, of course, but in the last analysis the most important factor is how the object can be used, and not how it can be adapted so that it will fit into a particular interior.

In view of the current economic situation, designers of consumer goods are coming in for a certain amount of criticism. How do you think designers should and could react to this situation?

Osko: I believe that the keyword is reduction. Quite apart from the crisis, we have always tried to design things at a low level of complexity. Our products are intended to have a clear concept and be as simple to create as possible. It would be nice if the kind of transparency which is being demanded at the political level also managed to to trickle down to the design level. The result would be 'honest' products.

Our design always involves the challenge of saying as much as possible while using the minimum amount of resources. I believe that this type of design will be very much in demand in the years to come, for both economic and ecological reasons.

If we look at it like that it's very useful that economic and ecological interests are coming closer together. It's only a pity that it takes an economic crisis to have this effect. Have you honestly noticed that your customers are becoming more interested in ecological design?

Osko: We have to admit that the interest on the part of the producers is not strong enough yet – you only have to look at the products which still dominate the market.

But our experience with Blå Station has been very positive. For them producing with locally sourced materials is a priority. At all events sustainability is much more of an issue than it was only five years ago.

On the basis of your products can you describe in concrete terms to what extent you design in an environmentally friendly way?

Deichmann: The principles which determine the cost efficiency of a product apply in the same way to its sustainability. We try to get the very best out of the most uncomplicated production methods. This is normally a step in the right direction.

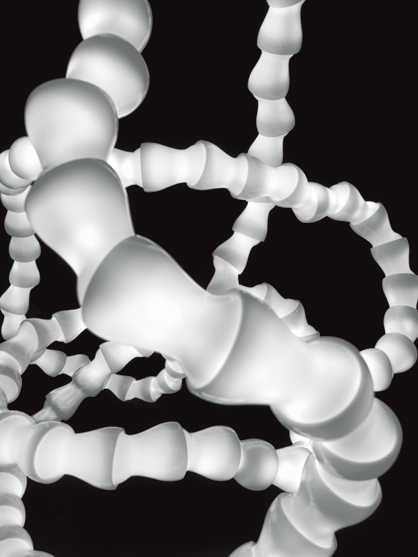

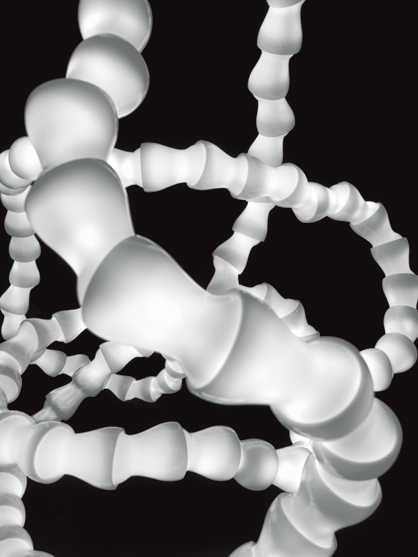

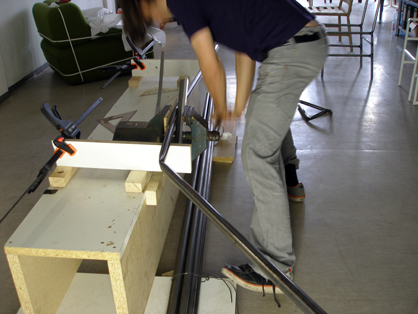

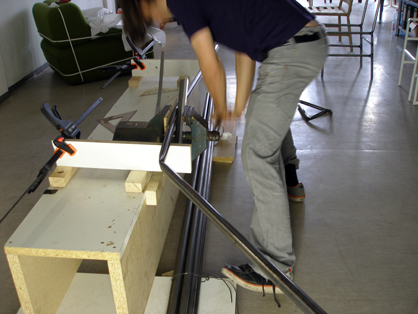

Let's take a look at our 'Clip Chair', for example. It consists of nothing more than a couple of slats with holes drilled in them which are fixed to a steel cable. The chair itself is in fact a soft design, which does not become stable until somebody sits on it. 'Pebble' consists of a simple metal frame, into which to upholstered elements are inserted, that's all.

Osko: Design is also ecological if it is timeless. In my opinion the criterion for good design is how long it lasts. By this I mean the length of its life in terms of quality and aesthetics.

In recent years German design has developed in the right direction, after the typical german functionalist movement á la Dieter Rams had left a gaping hole. Does anybody refer to your nationality?

osko: yes, the question of whether our design is typically German is always there in the background. But I believe that nowadays it's no longer possible to attribute product design to a single country. When we design a product we tend to see a company which the product might suit. I tend to think that the differences which we used to identify with countries and regions are now to be found among various manufacturers.

Deichmann. English as a common language has also broken down many barriers. Twenty years ago it was definitely much more problematic as a foreigner to work together with an Italian company, for example. That is is no longer quite as difficult today.

In Germany design is not regarded as especially important by the public in general. In countries like Denmark this is very different. If you ask a child there who Arne Jacobsen is, for example, you will be probably given the right answer.

Osko: I don't exactly know what the reason for this is. My theory is that people in Germany tend to have more of a do-it-yourself mentality, added to which there is the trend towards buying things as cheaply as possible. I don't think there is any other country with the kind of DIY-store temples we have here.

But wouldn't this be just the right starting point for the future of design? It must be possible to exploit this do-it-yourself mentality in some way.

Osko: Yes, our colleagues Vogt and Weizenegger tried this with their blueprint project. They developed instructions for interior furnishings which people could make themselves - unfortunately it didn't really take off, but perhaps it's an idea whose time will come soon.

'Straw Chair', in reference to Marcel Breuer, for the 90th Bauhuas anniversary

Like many young designers you attracted your first international interest at the Salone Satellite in Milan. You have now successfully managed the next step, you're getting orders and you can earn your daily bread with design. What advice would you give all the young designers out there?

Deichmann: The classic example, of course, would be Silvester Stallone: stick with it for as long as it takes until someone puts you in a movie or, as in our case, until someone wants to produce one of your designs.

osko: For the first seven years we lived from hand to mouth, and in my opinion design has to be your favourite hobby in order for you to stick it out for so long. It really is a job that requires passion.