"The style has always been the problem"

Texte par Nora Schmidt

Berlin, Allemagne

28.07.08

An interview with the Italian architect and designer Michele De Lucchi

For 30 years now Michele De Lucchi has vitalised and influenced the international design world with his convention-challenging ideas and working methods. He studied architecture in Florence before his friendship with Ettore Sottsass and Alessandro Mendini took him to Milan at the end of the Seventies, where he became one of the main activists in the provocative designer group Memphis. Although by his own admission he does not create his objects with an eye to specific demand or marketing requirements, he is nevertheless responsible for lasting bestsellers like the Tolomeo lamp for Artemide. In addition to his design professorships and responsibility for the design department at Olivetti, he also established the Studio De Lucchi at the end of the Eighties. Here he and his inter-disciplinary team have dedicated themselves to the entire range of design operations, ranging from graphics, products, exhibitions and interiors right down to architecture. Since the early Nineties he has, under his Produzione Privata label, also created small series of his designs featuring exquisite craftsmanship.

Michele De Lucchi with one of his countless, handmade wooden houses

Mr. De Lucchi, you have been working successfully as a designer for more than thirty years now, and have experienced a number of different eras. Where does design stand today?

Design is truly a kind of witness to history. Design documents the spirit of the age. Today we are at a very exciting stage, because there is no specific style. To me that's great, because as soon as a style develops there's no longer any progress.

After your architecture studies you worked for Alchymia, together with Ettore Sottsass, Andrea Branzi, Paola Navone and others. Alchymia is regarded as the predecessor group for Memphis, the group which in the Eighties created an international sensation with its projects.

Alchymia was something special, because it was the first design movement which based itself on the conceptual art of the late Sixties and the Seventies. That was a period when artists put down their paintbrushes and began a debate on their activities, their tasks and the significance of art. This movement also had an influence on architecture and design, instigated in particular by Peter Cook and Archigram. You could say that there was no design for almost ten years.

What exactly did you and your colleagues do during this time?

We debated, we staged happenings, developed metaphors. An attempt was made to approach architecture and design once more in an interdisciplinary manner. This was a fundamental development, because it describes the social idea of the architect. All at once our role as architects changed radically. We were no longer just technicians whose job it was to produce drawings and build houses – the intellectual debate became more and more important.

First Chair and End Table by Michele De Lucchi for Memphis, 1983

Did you never have the wish to work as an architect?

I actually planned only a few buildings, because I completed my studies right in the middle of this phase. However, I don't make a distinction between design and architecture. The two disciplines are very similar. Of course there are differences, but fundamentally the main aim is to create surroundings in which people can live and to design these surroundings in a way which stimulates their lives, which is very different from stimulating the market.

Today there are schools of architecture and schools of design, in other words we differentiate between these disciplines. Is this reflected in the work which results?

Oh yes, very much so. Designers often fail to take into account the dimensions of the space. Architects on the other hand neglect the dimensions of the objects. When I was studying architecture we used a different method from today. Architecture was created from the inside outwards. Today it's precisely the other way round. Present-day architecture makes this very clear. I like these projects, too, but they often produce strange internal spaces.

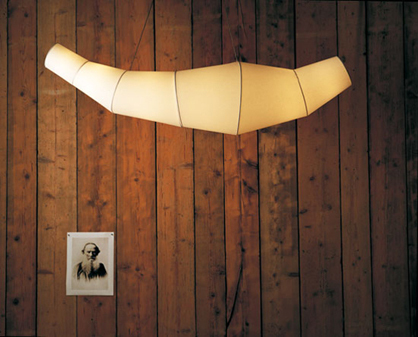

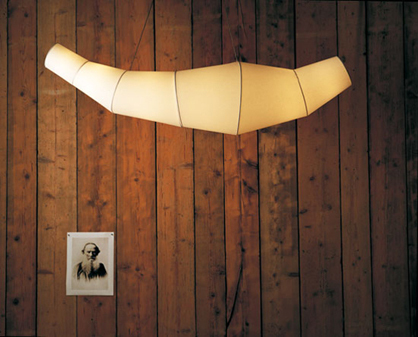

Giona by Michele De Lucchi and Alberto Nason for Produzione Privata

After Alchymia you established the Memphis group with people like Ettore Sottsass. Memphis stood for protest. What were you protesting against?

Memphis developed from the conceptual phase of Alchymia. With us it was less a matter of protest than of provocation. We looked for ways to break with convention, to call into question everything which was already established.

What was the convention?

The style. The style was always the problem. The style at the time was described as the "international style". For years this style had dominated design and architecture. However, it's very rare for an established style to lead to innovation. In contrast it's the task of a designer, artist or architect to present new views and perspectives. Creating new fields of vision also means imitating and perfecting what already exists. After all, we still continue to design cutlery, crockery and tables, although there's already no shortage of tables. The fact is that we want these objects to surprise us again and again. That's why we design new ones.

When we had our last Memphis exhibition in 1987 it turned out to be a very painful experience, because we realised that the provocation had been so successful that we had developed a style with Memphis. All at once people were copying us, and the Memphis style was appearing everywhere you looked. This was a positive sensation on the one hand, but on the other we were aware of the fact that we would have to put an end to it if we wanted to start anything new.

When is a product something "new"?

For me the objects which function really perfectly are not the most interesting ones. I'm more interested in all those which show me that there is ongoing development. This is the way in which innovation is generated. Ettore Sottsass, for example, didn't work for the market or for established furniture businesses. Nobody wanted to buy the objects he created, above all because they were too eccentric.

I like almost all of his projects.

But you've never bought one, have you?

I'm afraid they're outside of my price range.

Exactly. Sottsass products aren't sold as consumer goods. They're sculptures. And in spite of this Sottsass has had an enormous influence on the design of several generations. I like his projects because they show me that there is a future. They open the door for an optimistic look forwards.

Go by Ross Lovegrove for Danerka, Canova by Michele De Lucchi for Produzione Privata

Do any younger designers occur to you?

I admire Ross Lovegrove. His design seems to me to be very instinctive. He obviously knows how to operate in an analytical and rational manner while at the same time connecting his technical talent with an emotional response. This ability is what distinguishes good design.

In other respects there are a number of talented young designers. However, what I often find missing is curiosity. I've even observed this at the design schools where I teach.

Why do you think these young people don't have the necessary curiosity?

This is a problem of our age. Nowadays we have far too many possibilities. It has become much more difficult to take decisions. Industry, electronics, the internet – we're constantly faced with an enormous supply of things and as a result we lose our feeling for what is really essential. Instead of consciously analysing a matter, many decisions are taken at random and intuitively. However, the design process favours deliberate, well thought-through decisions. I believe that this is too much for many young designers.

After Memphis you founded your Produzione Privata studio, in which you design and produce limited editions. What were your reasons for this?

After Memphis I felt an urgent need to work together with my friends from old-established crafts – glassblowers, stonemasons from Carrara, these are all wonderful people and probably the last generation who will possess this kind of craftsmanship. In addition it goes against the grain with me to operate in a large company.

The limited editions of my products give me the freedom to experiment and to make mistakes. If you make a mistake in mass production it costs you dearly. It's a completely different process.

Macchina by Michele De Lucchi, Alberto Nason and Mario Rossi Scola, Trelissi by Michele De Lucchi and Aya Matsukaze for Produzione Privata

Macchina by Michele De Lucchi, Alberto Nason and Mario Rossi Scola, Trelissi by Michele De Lucchi and Aya Matsukaze for Produzione Privata

×

However, many designers want to concentrate fully on the design process, and are happy to leave the production side to a good manufacturer.

That's true. But when I am given a detailed briefing, telling me for example to design a table of wood with four legs, it completely paralyses me.

But mass production and a market-oriented approach are still a significant part of the job of a designer, or do you disagree?

There are products and there are projects. Products are made for the market and projects are visions. Both are important types of design. However, good projects rarely turn into good products.

Why do you believe that Italian design continues to be the most prestigious in the world?

Here in Italy we're in the fortunate situation of having lots of highly qualified craftsmen and small workshops which do a lot of the preliminary work for industry. This cooperation has a long tradition. Much of what you see at the Salone del Mobile consists of prototypes, and only few of these ever reach the production stage. At the same time, however, these prototypes form the foundation for the things which will be presented as new products the year after.

Thank you very much for talking to us, Mr De Lucchi.