The sound of silence: the PALMBERG Intelligence Series

Brand story by Markus Hieke

Schönberg, Allemagne

08.06.23

How well do we work with headphones in our ears? And why is complete silence not necessarily always optimal? In the second of three parts from the PALMBERG Intelligence Series – a series presented by office furniture manufacturer PALMBERG – neuropsychologist Lutz Jäncke answers these and other questions from a scientific perspective. Spoiler: Your favourite music is sadly not the optimal sound for the office!

A not insignificant factor in the office relates to that of acoustics. When designing work environments, planners should be aware of the effects on concentration of conversation, background noise and music – but also silence

A not insignificant factor in the office relates to that of acoustics. When designing work environments, planners should be aware of the effects on concentration of conversation, background noise and music – but also silence

×Perhaps you didn't know that listening to music is actually an activity, and if not, you might be interested in what Prof. Dr. Lutz Jäncke has to say on the theme of music and silence at work. The emeritus professor of neuropsychology at the University of Zurich has done extensive research on the influence of music on the plasticity of the brain, i.e. its malleability through experience, and has published over 150 papers on the subject of music. ‘I have studied musicians and worked a lot on auditory perception. How people perceive sounds, music, melodies, how they process them in the brain,’ says Jäncke. ‘And I've done studies on background music and the question of whether it influences cognitive performance, memory, etc.’ And this is what our conversation is all about: background noise and silence in the workplace and the difference between acoustic distractions and subtle musical sounds.

As a neuroscientist at the University of Zurich, Prof. Dr. Lutz Jäncke has conducted a wide range of research on the plasticity of the human brain and published studies on the influence of music, learning ability and irrationality, among other things

As a neuroscientist at the University of Zurich, Prof. Dr. Lutz Jäncke has conducted a wide range of research on the plasticity of the human brain and published studies on the influence of music, learning ability and irrationality, among other things

×When was the last time you heard Vivaldi's ‘Four Seasons‘? What does this music trigger in you?

The last time I heard it was three days ago at a lecture. You're alluding to a story that I always enjoy telling. And it really is the case for me, I measured it neurophysiologically: This music reminds me a lot of my time at Harvard Medical School in Boston in the mid-1990s. On weekends, especially in autumn, my colleagues used to drag me out on hiking trips.

Every time I hear this music by Vivaldi, especially ‘Autumn’, everything is present in my mind

I will never forget those colourful leafy forests for the rest of my life. That's a very important element, connected to a very important time for me in Boston. So every time I hear this music by Vivaldi, especially ‘Autumn’, everything is present in my mind. The colourful woods, the smell, the landmarks, it's all there. It's a wonderful example of how music can evoke memories in us. This ability to play such multimodal impressions through sounds in our head, like in a cinema, is remarkable.

Does Vivaldi only work for people who have similar memories associated with this particular music? Or is it the composition that has a universal effect here?

It is a phenomenon that is also associated with other pieces of music. But it is also important to note that the perception of music is culturally and experientially determined. Some music historians and musicologists claim that certain music has very special influences on us, independent of culture. I think that is wrong. Because it depends on how we access music. We know from research that we like what we hear often.

If you have something very complicated to work on, listening to music and solving this task at the same time is very difficult

There are studies on how children develop musical preferences. And they develop their preferences for exactly the music they listen to frequently. That's how cultural preferences for music develop. If you grow up in a musical household where Mozart is played, there is a relatively high probability that you will also like Mozart's music. If you always listen to pop music, Mariah Carrey all the way, then you likely won't want to have much to do with Mozart.

To what extent is this knowledge also important for the topic of the office? What optimal brain state do we want to reach at work? What should we be playing there?

The office work we have to do all day has different degrees of difficulty. You have to consider different things: do I work in an open-plan office, do I work alone, what tasks do I carry out? For example, if you have something very complicated to work on, listening to music and solving this task at the same time is very difficult. Because that's a double activity – our brain doesn't like that. In order to process something complicated, our brain needs attention and concentration.

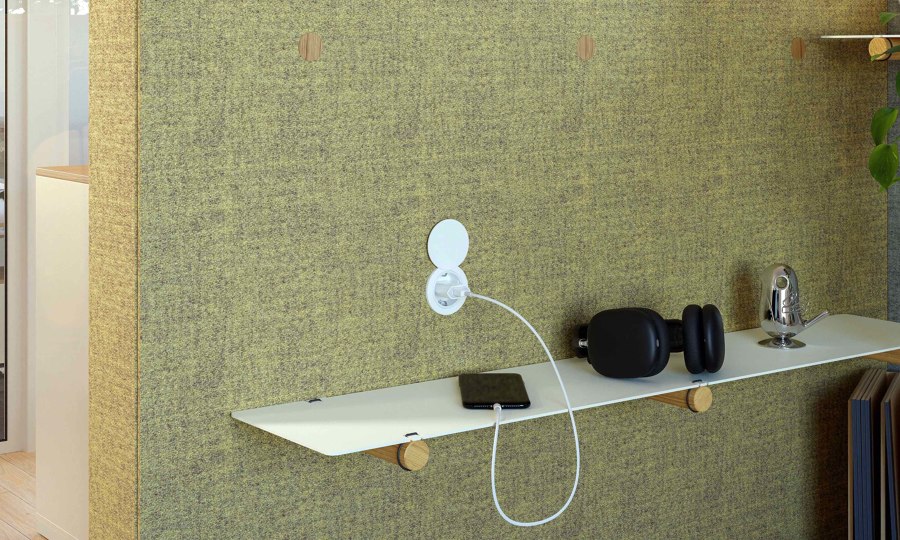

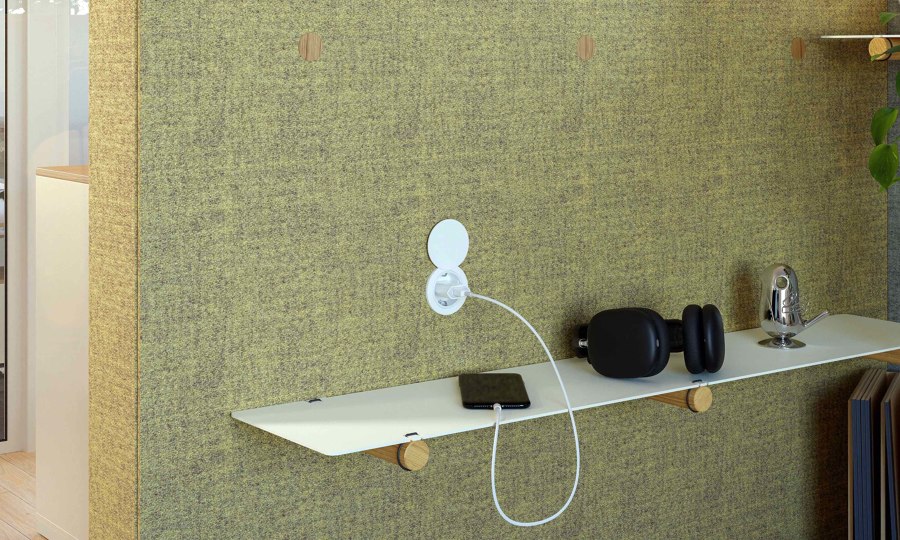

Headphones can help in the workplace for short periods during which the brain is processing complex thoughts or learned material, or for better concentration – but It depends on the ‘right’ sounds

Headphones can help in the workplace for short periods during which the brain is processing complex thoughts or learned material, or for better concentration – but It depends on the ‘right’ sounds

×And this is only possible to a limited extent in an environment where people are talking on the phone, keyboards are clattering and there is possibly street noise from outside…

If you work in an office where there are noises all around you that you can't predict, your brain is constantly forced to make orientation reactions – that's the crucial problem. They are automatic reactions, you can't really suppress them. If you are working now and something clicks, your brain tries to orient itself there immediately and you are torn away from your work. You then need ten, fifteen, twenty seconds to find your way back to the matter at hand. This is a hindrance for work in the office.

How do you explain why it is so difficult for us to block out the things around us?

You have to think of it like this: The frontal cortex is the area of the brain that exerts a top-down influence on the limbic system. These are the brain structures with which we act on our impulses: I'm hungry, thirsty, this is interesting and so on. The frontal cortex inhibits us and that costs energy.

Noise cancelling works perfectly to distract yourself from distracting, unpredictable stimuli

For example, if you have to concentrate because you have an important submission the next morning, then you can really concentrate on this task, even if it's really noisy – your frontal cortex is active. At first, you can concentrate well, despite the super interesting things happening all around you. When this concentration power diminishes, however, your attention wanders in the direction of these other interesting and distracting stimuli.

Working together in an open-plan office is fun, but is a challenge to concentration. Areas for retreat as well as telephone or meeting pods make sense

Working together in an open-plan office is fun, but is a challenge to concentration. Areas for retreat as well as telephone or meeting pods make sense

×You can't always shut yourself off completely, so can music through noise-cancelling headphones still represent the lesser evil?

I recommend putting on headphones. Noise cancelling works perfectly to distract yourself from distracting, unpredictable stimuli. The only thing is that you have to choose music that doesn't somehow excite you very emotionally, or where verbal material is presented that makes you unconsciously focus on the language. It should be something that is predictable, that is important. Sounds that our brain can process loosely and casually are good: Philip Glass, for example, piano music or lounge music that meanders along. In this context, listening to music is interesting.

Would you recommend background noise via loudspeakers for offices?

It always depends on what people have to do, the time of day and also individual tastes. If it's late in the evening and people are getting tired, then such background noise can be good. It can emotionalise us, activate us and counteract tiredness. However, one must not forget that we humans are very reactive.

We can't always be perfectly focused for eight or ten hours a day. You have to get out of this cognitive focus every now and then and let your thoughts run free

Let's say someone puts on some pop music, but you hate pop music, so you get annoyed because your brain is being occupied by music you don't like. That triggers a reaction, a resistance. Better, in this case, would be music playing in the background in such a way that its genre can hardly be identified. Music can help in this way in the morning, after lunch or towards evening, to create a mood.

Why after lunch?

After lunch, we tend to sag a little. This is what I always call the postprandial midday coma. All the blood goes into the portal system and there's a bit less oxygen in the cortex, so a lot of people become a bit tired. And if there's a little activation in the background, it helps us to get back up. Sometimes music can also act as a can opener of sorts when you have a blockage. But don't forget that in difficult situations, when you have a problem to solve, you have to be careful not to get distracted. If you have music that catches your attention, then it can affect your attention. It may bring back some memories and make you feel great, but such conditions are unfavourable for problem-solving processes.

Noise-cancelling headphones can be beneficial, while listening to our favourite music or alternatively, music that is completely unknown to us can be distracting. Predictable background music is the better option

Noise-cancelling headphones can be beneficial, while listening to our favourite music or alternatively, music that is completely unknown to us can be distracting. Predictable background music is the better option

×What about quiet areas for the office?

I think quiet spaces are appropriate. But one must not underestimate these distractions either. That means we have to recognise that we have occasional lifts in mood – especially during the workday. We can't always be perfectly focused for eight or ten hours a day. You have to get out of this cognitive focus every now and then and let your thoughts run free. And that's where music comes in very handy, by the way. How exactly this is organised in an office is another story. With a music room, for example, or a relaxation room, as Google does, or with recreation rooms, as they are called at Apple. Employees can do all kinds of things there: make music, listen to spherical sounds, experience visual impressions. Of course, these are ideas for which a company must have the capacity in the first place. But headphones can also help – today, of course, you can put together all kinds of things on your smartphone.

Listening to engaging background music during a work break can be good for learning processes and can help when it comes to tackling challenging problems

Listening to engaging background music during a work break can be good for learning processes and can help when it comes to tackling challenging problems

×Conversely, can complete silence also be an obstacle to concentration?

Generally speaking, silence is good for processing difficult, cognitive tasks. However, we do not like silence as a matter of principle, but always prefer sounds. The background is quite simple: our brain is an organ that does not like uniformity. It always interprets things into uniformity but it needs variety. Take this as an interesting example: Let's assume you would now spend thirty minutes in silence, highly concentrated, learning something or working on something. In order to process this, you would then need a break of ten or fifteen minutes in which you do nothing. If you listen to exciting music that activates you, then you will be better able to retain and process what you have done before. In other words, this interplay of silence, rest and activation has a favourable effect on solving complex tasks and on learning. There is a simple biochemical process behind it: activating your brain with the help of music releases certain transmitters. This in turn promotes the formation of synapses. Memory experiments have shown that this increases retention by about 30%. Complete silence, on the other hand, is unpleasant after a certain point.

Too much silence can also become unpleasant at some point: ‘Our brain is an organ that does not like uniformity. It needs variety,’ says Jäncke

Too much silence can also become unpleasant at some point: ‘Our brain is an organ that does not like uniformity. It needs variety,’ says Jäncke

×In many companies, varied office spaces are currently in demand, with sofa lounges, places to retreat, telephone boxes, and the like. How do you rate these so-called multi-spaces compared to individual offices or classic open-plan offices?

In general, I think such multi-landscapes are very good. They will make a lot of sense if workers have self-discipline. If they know when it makes sense for them to go here or there. Then they will choose the environment that is best for their current state and the task at hand. Variety is important – as long as you stay on track!

© Architonic

Head to the Architonic Magazine for more insights on the latest products, trends and practices in architecture and design.