Design Israel

Texte par Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suisse

03.07.10

The completion of Ron Arad's small-scale masterpiece that is Israel's new Design Museum Holon signals a kind of design coming-of-age for the country. With its current design scene set to grow even further, Architonic talks to a number of established and emerging designers, curators and educators about the significance of Israeli design and where it's heading.

Detail of the Design Museum Holon, designed by Ron Arad; photo Yael Pincus

Israel. It's fair to say that the mere mention of the country can often evoke a strong response in people, whatever their political persuasion. One thing the world isn't short of is opinions on the state of affairs in the eastern Mediterranean. What is in short supply, it often seems (and regardless of your take on the situation), is the real possibility of change in the region, which might bring about a viable, long-term political stability.

The Design Museum Holon, designed by Ron Arad; photo Yael Pincus

If we view design in terms of a constructive force, one that works to improve our lives, even on the most prosaic of levels, one that effects change, then the recent emergence of a convincing Israeli design scene – both in terms of designers practising at home and those working abroad – is a welcome development. With the small, but striking, Ron Arad-designed Design Museum Holon opening its doors a couple of months ago, signalling to local and international audiences alike Israel's serious engagement with design, there's never been a better time to look at how the Israeli creative community is putting their country on the global design map.

The newly opened Paradigma design gallery, Tel Aviv

'The museum is the biggest and most prominent object in our collection,' explains Galit Gaon, creative director of the Design Museum Holon, with obvious pride. If there's one thing that signposts the arrival of a true contemporary design culture in Israel, it's this building, at once a space for showing design, and, as Galit points out, a compelling design piece in itself. British-based Arad, probably the best-known designer in recent times to come out of Israel, and whose renown was recently confirmed by a retrospective of his work at London's Barbican Gallery, has created a building whose distinctive, lyrical form sets up the promise of great things inside. Or as Galit puts it: 'The museum is all about design, about experience, about relationships, so it has all the values of a very good museum even before you enter the exhibition.'

Tel Aviv's new commercial design gallery, Paradigma

The new museum is place of contradiction, which only serves to make it all the more fascinating. Firstly, it's a locally funded project. The building of 'Holon' into its name (Holon is a small city of just under 170,000 inhabitants, lying south of Tel Aviv) communicates quite clearly the community to which the institution in the first instance belongs. As part of Mayor of Holon Moti Sasson's remarkable drive, almost François Mitterrand-like, to create a cultural legacy for the city (eight different museums have been established there in the past ten years), one of the Design Museum Holon's functions is to put design on the agenda in local people's lives. 'Design is about people. It's about the community,' says Galit. 'It's about choosing well. If you teach people to choose well, our life as a city will be better.'

But the museum also has international aspirations. It's not by chance that star-designer Arad received the architectural commission. And this isn't a venue for Israeli design alone. Galit is quite clear about this. 'This is not an Israeli design museum. It's an international one. We have an international view. It's important to show Israeli designers alongside international ones to explain to audiences that we are part of the world, that Israeli designers are part of the global design tribe. We are not different.' While its curatorial policy aims high, the building itself also punches above its weight. Intimate in scale, it has a visual presence that exceeds its literal, physical one. With its highly sculptural, ribboned façade, made from Corten weathering steel, it's certainly not a shy structure. This is architecture as cultural catalyst. And its effects are already being felt.

'The design market in Israel is still in its infancy,' says Anat Benvenisti, owner of Paradigma, a new commercial design gallery in Tel Aviv. 'However, the opening of the design museum in Holon has brought design into the spotlight and created a buzz.' Benvenisti, who opened the gallery 'because there was no real platform in Israel that exhibits design-art for design lovers and design collectors', has been quick to recognise the ripple effect that the arrival of a cultural hub like the Design Museum Holon creates. 'The museum has given the design scene a push. Even some art galleries are looking to represent designers as well. Education takes time, though, and only time will tell if a wide enough collector base will be created.'

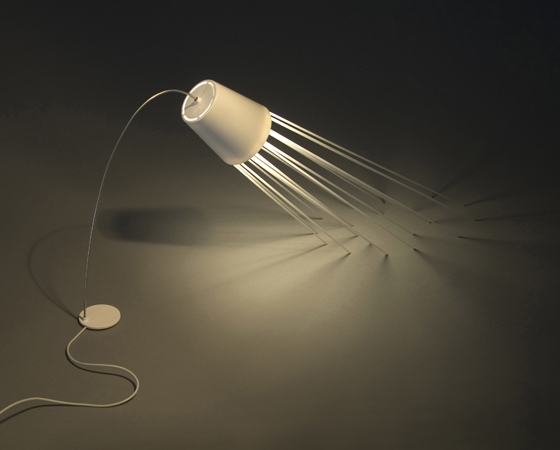

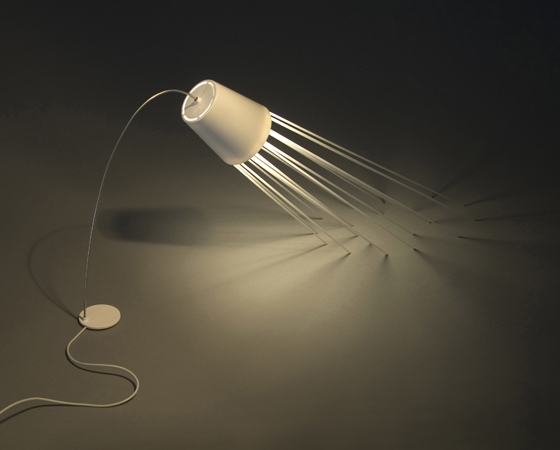

Naama Hofman's surprisingly neon-looking '001' LED lights

But limited-edition design, with its ability to divide opinion on its merits, is just one part of what makes a healthy design scene. Where do young designers fit into such an economy? 'One of our gallery's missions is to promote young, talented designers,' Benvenisti is keen to point out. Galit Gaon is equally committed to showcasing emerging talent. But she's also eager for them to realise their potential by exhibiting their work elsewhere. 'The most important place to show Israeli design is not in Israel,' she suggests. 'It's Milan, New York, Paris, wherever. These guys have to go out there in the world and work. If I show their work here, it's nice, but this is not their biggest goal.'

Tel Aviv-based design studio Bakery, who are (from left to right) Gilli Kuchik, Ran Amitai and Gil Sheffi

Tel Aviv-based design studio Bakery, who are (from left to right) Gilli Kuchik, Ran Amitai and Gil Sheffi

×And abroad young design graduates have, indeed, gone, presenting their work at leading international design fairs and other fora. A number decided to show at this year's SaloneSatellite in Milan, the platform dedicated to emerging designers that runs alongside the city's annual Salone del Mobile. Appearing under the auspices of d-Vision, a high-powered industrial-design internship programme founded in 2005 by Herzliya-headquartered multinational plastics manufacturer Keter, 15 design graduates presented 'On/Off', a collection of objects that addresses the issues of energy consumption and technology in lighting by using LED in an innovative and compelling way. Curated by Professor Ezri Tarazi, practising designer and head of the industrial design department at Jerusalem's Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, the project's aim was ‘to tell a story in each object in a simple and clear way that would surprise the viewer’.

'Nature of Material' stools, made from from folded laser-cut aluminium sheeting, by Ran Amitai of Bakery

'Nature of Material' stools, made from from folded laser-cut aluminium sheeting, by Ran Amitai of Bakery

×This new generation of Israeli designers are conscious of an evolving design culture in their country and are keen to be active participants of it. One of the class of 2010, David Keller, whose family emigrated to Israel from Russia when he was young, sees Israel's very ethnic diversity as part of its creative strength. 'Israel is a community of immigrants,' he says. 'It's a young country. I live in Jerusalem, where everything is mixed. This ethnic-hybrid culture provides Israeli designers with new ideas.' Sounds great, but what about the reality of long-term employment in Israel for graduates of design? 'Well, it's not easy, which is why I think many industrial designers move towards art, or the place between art and design. There's a reason why people try to work in Europe. But if you try long enough and you're good enough...'

Detail of 'Elastic Wood' chair by Gil Sheffi of Bakery

Fellow design intern Etay Amir identifies, too, a strong emphasis on concept in current Israeli design, one borne out of necessity, he argues. 'Because of a relative lack of design awareness in the local industry, designers jump on any opportunity they have to create – competitions, galleries, etc. This makes design look more artistic and less functional.' It's certainly true that, up until now, Israeli design has often (if one is to venture an attempt at defining a national 'style', which is always a tricky enterprise) been characterised by the 'ready-made', a type of work that makes use of found or low-cost materials, usually resulting in one-off pieces. Amir is resolutely industrial in his approach, however, in spite of the fact that he recognises that the design industry in his country is still somewhat nascent. 'It's hard to be a "big" designer in Israel at the moment,' he says.

Gilli Kuchik of Bakery's 'Industrial Upholstery' chairs

For Naama Hofman, a recent graduate of Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, who showed in the Zona Tortona during this year's Milan Salone del Mobile, the past popularity of the 'ready-made' as a form of creative expression for designers can be put down to the limited opportunities for industrial production previously, but also 'a general feeling of instability that prevents long-term planning. Recently,' she says, 'there has been an awakening on the part of the younger generation of designers and an openness and adjustment to the global atmosphere. This makes it difficult to define "Israeli" design.' For Hofman, though, it is precisely Israel's lack of 'a long history of design and technology that makes people think in non-traditional ways and to observe things from a different perspective.' Innovative thinking on the part of young Israeli creatives has, for her, a lot to bring to the global design table.

Shay Alkalay and Yael Mer, aka Raw Edges, at Design Miami Basel 2009, where they were named among the event's 'Designers of the Future'

Shay Alkalay and Yael Mer, aka Raw Edges, at Design Miami Basel 2009, where they were named among the event's 'Designers of the Future'

×Ezri Tarazi, who has forged a successful and varied career in design for himself within Israel (in addition to teaching and practising as a designer, he also did a spell as partner of IDEO's Israeli office), sees 2010 as a turning point in the country's design history. 'It's the gathering of many aspects of design,' he says. 'A culmination of processes that started a long time ago. In the last ten years, let's say, a lot of Israeli designers needed to leave Israel in order to succeed. Design in Israel came from a very small circle of designers.' For Tarazi, the internet has actively slowed this career-related-emigration trend, connecting Israeli designers with the global design industry in terms of influences and the dissemination of their own ideas. He cites the Design Museum Holon as another development that demonstrates Israel's design coming-of-age.

But it's design education, according to Tarazi, that is also driving the growth of design in Israel, at the same time as responding to an increased interest in it. In addition to Bezalel, Shenkar, and the industrial-design department at the Holon Institute of Technology, a number of other small schools have opened in the last few years. 'A lot of people want to study industrial design. We've got a lot of graduates,' he says. Three of those graduates, Gil Sheffi, Gilli Kuchik and Ran Amitai, who together form Tel Aviv-based design studio Bakery, and whose polished work attracted a great deal of attention in Milan this year, are keen to stay in Israel to develop their practice. 'We really hope we can continue to work from there,' says Sheffi. 'As strange a country as it is, we love it.' 'We're hoping that industry will embrace design even more, and especially young design,' adds Kuchik. Amitai jokes, however, that 'we'd move if we got the right offer.' (Perhaps said only partly in jest...)

'Stack' chest of draws by Raw Edges for Established & Sons, which is included in MoMA's permanent collection

'Stack' chest of draws by Raw Edges for Established & Sons, which is included in MoMA's permanent collection

×Two young design studios that have made a name for themselves in the last couple of years, once choosing to practise in Israel, the other establishing itself in London, are Reddish and Raw Edges. Both are male-female double acts, producing work that is highly contemporary and conceptually strong. Tel Aviv-born Yael Mer & Shay Alkalay, who make up Raw Edges, both graduated from Bezalel and went to the Royal College of Art in London to study under Ron Arad. ('His door was always open,' says Mer.) There they've remained, creating an impressive and technically innovative body of work for big design-brand names such as Established & Sons and Cappellini. They were recognised as Designers of the Future at last year's Design Miami Basel, just one of the plaudits they've received. So, why didn't they move back to Israel after their time at the RCA? 'London is such a great networking place,' according to Mer. 'It just felt like it was the first step of being a designer.' Mer and Alkalay also joined Okay Studio, a London-based, very international collective of young designers, who exhibited together and generally lent each other support. 'Sometimes, when you try to do your own stuff at the beginning, you get lost if you're by yourself,' Mer explains.

'Tailored Wood Bench (TWB)' by Raw Edges for Cappellini

When it comes to the idea of an Israeli design scene, Mer chooses to identify herself in relation to it as a 'London-based Israeli designer'. That's not to say that she's not active within Israel itself. She and Alkalay often run workshops for current design students at Bezalel. Naama Steinbock and Idan Friedman, aka Reddish, are also active in design education. Both graduates of the Holon Institute of Technology, Naama has taught there since 2006. Their story is perhaps a counterpoint to that of Raw Edges, insofar as they've developed an award-winning practice at home in Israel. It's not been easy, though. 'In order to have a design career in Israel, you really have to love the practice,' says Friedman. 'But the design scene's potential is getting bigger. The Israeli public is learning to appreciate design, companies are starting to acknowledge its value, and the designers themselves are starting to think globally.'

Idan Friedman and Naama Steinbock, who, together, make up design studio Reddish

Reddish certainly think global, with their work often being shown abroad (as well as appearing in the usual design blogs). 'We prefer to work from here, but we travel as much as possible,' they explain. 'It is really enriching and helps us to stay open-minded.' But it is the local, in terms of the traditional material culture of Judaism, that has provided the starting point for some of Reddish's most fascinating projects, their series of reworkings of the 'menorah' being an example of this. 'We find ourselves making social comments in some of our work,' they say. 'But these are always subtle comments.'

Is there a place in Israeli design for such commentary when it comes to politics, though, considering how large they are writ in the region? Are Israeli designers inclined to use their work to make political comments, or, precisely because of the omnipresence of politics, keen to avoid it? Although Bakery's work to date hasn't engaged with politics, Gil Sheffi hasn't ruled this out: 'In Israel, politics is a big issue. It's pretty obvious that they will inform design.' David Keller also sees politics as informing design in Israel, be it directly or in a discreet manner. 'Your creation is driven by where you live,' he says succinctly. Naama Hofman draws the distinction between more conceptual design work and industrially manufactured objects, when it comes to politics: 'The political situation in Israel is problematic, therefore it's advisable to keep politics out of design for mass production. No one wants left-wing milk and right-wing chairs.'

It is precisely his work outside the industrial system that Ezri Tarazi has used as a forum for political comment. His 2008 'Per Capita' exhibition in Basel featured, among other pieces, a sofa called 'Crowded', consisting of a chaotic aggregation of rock-shaped pillows made of parts of various national flags, stitched together in a seemingly random fashion, and 'DeFocus', a set of armchairs made from old Israeli road signs, bearing fragments of the word 'Jerusalem' in three different languages. But it's perhaps his 'New Baghdad Table', an intricate aluminium piece whose surface represents the diversity of the Iraqi capital city and which suggests, in the designer's words, 'that there is more than one truth and that truths can live together', which has been most controversial. 'There are places both in Israel and in America where the table couldn't be shown because it would have looked like a criticism of US policy,' explains Tarazi.

'DeFocus' armchair by Ezri Tarazi, made of old Israeli roads signs on which the word 'Jerusalem' appears in three languages

'DeFocus' armchair by Ezri Tarazi, made of old Israeli roads signs on which the word 'Jerusalem' appears in three languages

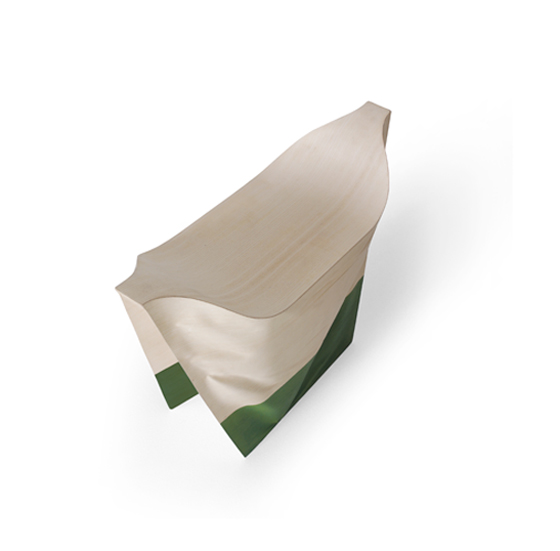

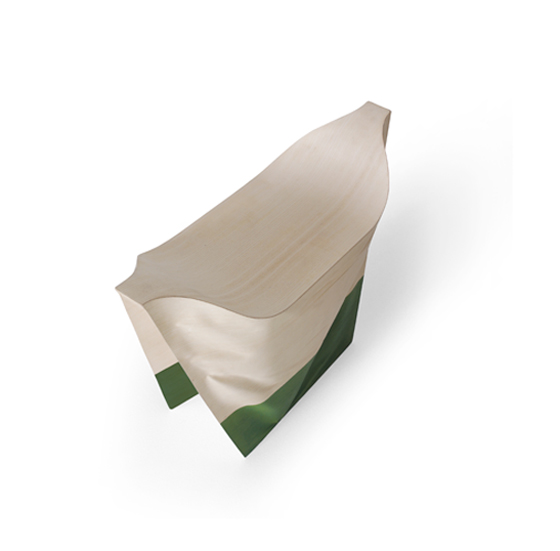

×Political comment doesn't come any more direct than Shenkar design graduate Ron From's 'Goods from Israel' collection of chocolates, however, which, more bitter than sweet, uses irony in a powerful and effective way to reference the country's state of affairs. The West Bank Barrier, a map showing Israel's borders and even artillery rockets from Gaza are all given the confectionary treatment. Presented in beautiful packaging, their delicateness is at odds with the stark reality of the situation to which they allude. Such work might be considered all the more brave in the context of the Israeli government's recent design policy. 'Having realised how important design is for the local economy, a lot of effort has been put into establishing collaborations between designers and industry,' explains Idan Friedman of Reddish. Moreover, Ezri Tarazi has been meeting with government representatives to discuss a possible programme of state funding, beyond design education, for designers to develop products. He describes it as 'another revolution'.

Design that engages with politics, be they local, regional or global, is perhaps what Galit Gaon from the Design Museum Holon is referring to when she talks about 'designing for change and not designing for one's own profit'. She's not sure yet what role the museum is going to play politically, or if indeed it will have a political dimension to it ('I'm not sure it will, but I'm also not sure it won't,' she says, with genuine open-mindedness), but it's clear to her, nonetheless, that the institution has an active role to play in underscoring the value of design in social terms. 'Design and compassion, design and patience, design and dialogue. The role of design in our world should be more clear, and designers should take steps in this direction. I hope the museum will make a significant statement about that.' With Israel's design culture set to continue growing, such statements can't be made too loud or too clear.

'West Bank Barrier' from Ron From's 'Goods from Israel' chocolate collection

'The Qassam Rocket from Gaza' by Ron From as part of his 'Goods from Israel' chocolate collection

.....