Go Your Own Way: Tobia Scarpa

Texte par Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suisse

09.02.14

A chip of the old block Tobia Scarpa certainly isn’t. Son of acclaimed architectural maestro Carlo Scarpa, the innovative designer, who turns 80 next year, was determined from the outset to plough his own creative furrow, in spite of his architectural training. His legacy is a raft of game-changing furniture and lighting pieces that test the bounds of what’s materially and technologically possible. Architonic met up with Mr Scarpa, Jr, at the Cassina showroom during this year’s imm cologne to discuss creativity, family and falling out of love with Alvar Aalto’s tables. Whatever you do, don’t call him an architect.

'I appreciate everything I’ve done, while recognising the limits of it.' Architect and designer Tobia Scarpa reflects on his creative career as he approaches his 80th birthday

'I appreciate everything I’ve done, while recognising the limits of it.' Architect and designer Tobia Scarpa reflects on his creative career as he approaches his 80th birthday

בLike father, like son’ goes the old expression.

Not in the case of soon-to-be-octogenarian Italian architect and designer Tobia Scarpa, however. Son of the renowned Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa, who was responsible for such projects as his native city’s Fondazione Querini Stampalia and its Olivetti Showroom, as well as the Brion Cemetery in San Vito d’Altivole, Tobia’s creative trajectory over the course of the last six decades has been informed to a large extent by a deep-seated desire, possibly a need, to define himself against his father’s identity as a master of architecture.

Tobia Scarpa speaks as part of a panel discussion at Cassina's Cologne showroom during imm cologne 2014 on the golden age of Italian design. On his right, Florian Löhle, North Europe Country Manager for Cassina

Tobia Scarpa speaks as part of a panel discussion at Cassina's Cologne showroom during imm cologne 2014 on the golden age of Italian design. On his right, Florian Löhle, North Europe Country Manager for Cassina

בI didn’t want to compete with him,’ he states candidly at the start of our interview. Having studied architecture, the young Tobia decides to focus his activities, for the most part, on designing furniture and other forms of product. ‘I had the idea that my father was the architect,’ he explains.

The occasion is a panel discussion at the Cassina showroom in Cologne during the January furniture fair, where Scarpa, along with Professor Axel Kufus from the Universität der Künste Berlin and Elle Decoration Germany’s Editor-in-Chief, Christine Bürg, are discussing the origins of Italian design. The event’s commercial context is Cassina’s recent acquisition of the iconic brand SimonCollezione (founded in 1968 by Dino Gavina) and with it a raft of classic designs by the likes of Marcel Breuer, Kazuhide Takahama, Meret Oppenheimer and Man Ray, as well as both of the Scarpas, Carlo and Tobia.

Cassina’s acquisition of the iconic brand SimonCollezione brings with it designs by the likes of Marcel Breuer and Kazuhide Takahama, as well as both of the Scarpas, Carlo and Tobia. Shown here, Carlo Scarpa's 'Doge' (top) and 'Florian' (above) tables

Cassina’s acquisition of the iconic brand SimonCollezione brings with it designs by the likes of Marcel Breuer and Kazuhide Takahama, as well as both of the Scarpas, Carlo and Tobia. Shown here, Carlo Scarpa's 'Doge' (top) and 'Florian' (above) tables

×Families are complex things. This we know. Tobia Scarpa’s conscious decision to plough a furrow that is in contradistinction to the one his father elaborated through his architectural enterprise doesn’t for one second mean the son doesn’t respect his father’s creative legacy. On the contrary. In Cologne, he talks about Scarpa Senior’s highly architectural tables for SimonCollezione with detailed knowledge and pride. That said, he’s quick to express his unease with the title ‘architect’ when applied to him, regarding himself first and foremost a designer. And his work (often the result of close collaboration with his wife Afra) for some of the landmark manufacturers in the Iandscape of Italian design, including B&B Italia, Flos, and, of course, Cassina, should leave us in no doubt about this.

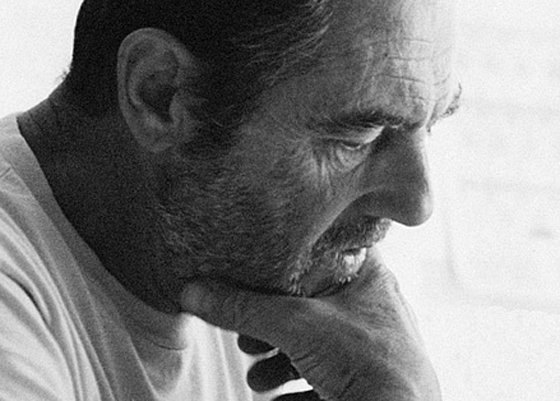

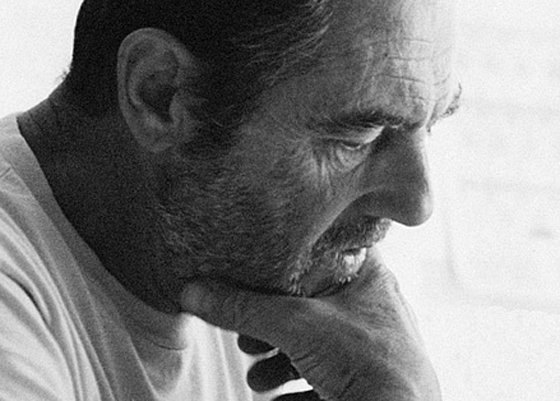

'The truth is I became a designer because I didn’t want to interfere with the work of my father', says Tobia Scarpa, son of renowned Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa, shown here

'The truth is I became a designer because I didn’t want to interfere with the work of my father', says Tobia Scarpa, son of renowned Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa, shown here

×Detail of Carlo Scarpa's 'Orseolo' table for SimonCollezione, now part of the Cassina brand

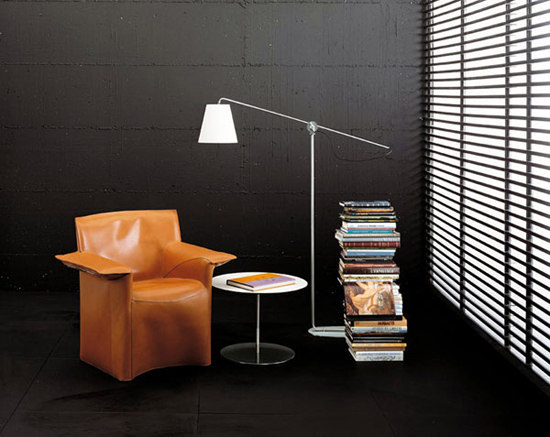

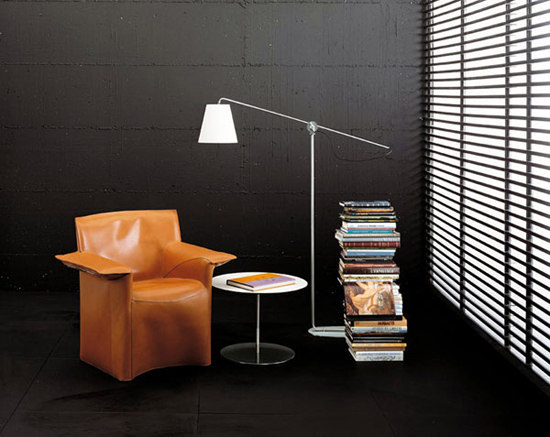

Shaping, in fact driving, all of Tobia Scarpa’s designs is the need to innovate. To do things differently. Not for the sake of it, but rather to push back the boundaries of what’s materially and technologically possible, and those of the designer’s own competence. Thus, we have pieces such as the 1966 ‘Coronado’ sofa and armchair series for B&B Italia, with its game-changing internal construction, the ‘Biagio’ lamp of 1968, designed for Flos and fabricated from one single block of marble, and the frameless foam ‘Ciprea’ armchair, made by Cassina and launched in 1968. (The first two designs are still in production.)

Launched in 1968, Tobia Scarpa's 'Biagio' lamp for Flos, carved from a single block of marble

In some senses, Scarpa was always ahead of his time, such was his commitment to experimentation, his furniture and lighting a kind of materialisation of his constantly research-oriented thinking. Not possessing prior knowledge of how to do something was never considered an obstacle. Such a pioneering approach was, he admits to me in our conversation, however, at times a touch frustrating for the manufacturers with which he partnered. But where would we be without those paradigm-shifting design thinkers and practitioners who imagine a material world better than the status quo? Tobia Scarpa, we salute you.

The game-changing 'Coronado' armchair for B&B Italia, launched in 1966. 'Before I invented this, it took three hours to build the armchair, and after that 15 minutes,' says Tobia Scarpa

The game-changing 'Coronado' armchair for B&B Italia, launched in 1966. 'Before I invented this, it took three hours to build the armchair, and after that 15 minutes,' says Tobia Scarpa

×....

You described yourself at the start of today’s panel discussion here at the Cassina showroom in Cologne as ‘just an old man’, but the truth is your design legacy is a significant one. How do you feel about this legacy as you approach your 80th birthday?

Well, I like my work. But the truth is I became a designer because I didn’t want to interfere with the work of my father (Carlo Scarpa). I just felt it wasn’t nice to come along as a young architect and do the same work as my father. I had the idea that my father was the architect and I didn’t want to compete with him.

At the end of the day, there is no great difference between a house that is built and one that is inhabited, where people live. But there is, I feel, a difference between building a house and making the furniture that goes inside. Moreover, in Italy there’s a law that prohibits people who don’t have a degree in architecture from planning houses, whereas everyone can design furniture or other objects.

Tobia Scarpa's stackable 'Boomerang' chair for Meritalia

Do you feel that your training as an architect has directly informed your practice as a designer?

I’ve never really thought about that. I don’t believe there’s any difference between the two things. I don’t even think there’s any difference between planning a space ship and a house. There are people who like doing one thing and there are people who like doing another. For example, I tried to design sail boats, just to see what happened and to find out what I was able to without any background knowledge. I did the first project without preliminary studies or calculations, but definitely with technology – we used materials that were not on the market yet. But I didn’t win in the world championships, but it wasn’t bad!

There is a very pioneering, innovative element to all of your design work. Given that you’re associated with so many of the most-respected manufacturers from Italian design history, do you think that design in the 1960s and 70s was characterised by more of a pioneering drive, compared to nowadays? Was it more ambitious in terms of wanting to changes people’s lives?

Well, the manufacturers then were really a bit ignorant. They just didn’t know anything. They didn’t even know how to do their own profession.

Launched in 1966, Tobia Scarpa's 'Foglio' wall lamp, with its powder-painted, pressed-steel wings, provides diffused illumination

Launched in 1966, Tobia Scarpa's 'Foglio' wall lamp, with its powder-painted, pressed-steel wings, provides diffused illumination

×Does that mean then that there was more freedom back then? Was there more faith in the designer?

Absolutely. Precisely because they didn’t understand what we were doing. This gave us so much more freedom. Once I invented an armchair – called ‘Coronado’ – and developed the technique by myself, assembling the whole thing with just two screws. It was manufactured first by C&B and then B&B. Before I invented this, it took three hours to build the armchair, and after that 15 minutes. But ultimately they decided to follow fashion trends, whatever was fashionable, and I was left feeling very disappointed.

What I was trying to do as far as chairs and armchairs are concerned was really to promote industrial manufacturing. As far as the lamps were concerned, that was more difficult as there were technical problems that I really couldn’t control. I couldn’t just change everything. But, for example, I designed a bed that was based on a flexible layer; but the market at the time was controlled by the slat manufacturers, and as a consequence it wasn’t produced, because these manufacturers held the power. So it became a niche product and not a widely sold product.

The problem was at that time that a product had to find its way by itself: no advertising, no sales support, absolutely nothing. And this is what is different now. For example, here (at Cassina) you see a clear will to promote these products.

Tobia Scarpa's 'Bia' armchair for Meritalia, with its single-piece cover

What do you think of the state of Italian design today? Is it right to speak of it having a golden age sometime in the past?

I think design is still sort of the same. There’s no real research. I was always attempting to discover new technology. When the marble lamp ‘Biagio’ was designed, I tried to work out the potential of the machines. This kind of product hadn’t been manufactured much by machine before. So we put it on a mechanical machine, this piece. Nowadays, there are machines that work like a hand, like five humans. Back then, there was nothing like that. That said, today there’s still space to invent new technologies.

For me it’s really fun to discover something that stimulates me to create an object, because the object is, I believe, a gift that honours the intelligence of the other, the other person. The person who receives it, encounters it. And the technology that is inside is my merit, my reward.

Is there a designed object that you wished you had designed, rather than someone else?

Yes, someone who stole one of my ideas! No, something I like are the tables of Alvar Aalto. It’s only once I’d bought them that I saw how they were manufactured, at which point I wasn’t that convinced anymore. But generally I’m happy with my own work. I appreciate everything I’ve done, while recognising the limits of it.

Tobia Scarpa: 'For me it’s really fun to discover something that stimulates me to create an object, because the object is, I believe, a gift that honours the intelligence of the other'

Tobia Scarpa: 'For me it’s really fun to discover something that stimulates me to create an object, because the object is, I believe, a gift that honours the intelligence of the other'

×Your network of family relationships, your father a renowned architect and your wife also a talented architect and designer… How important are close relationships with other creative people and how do they influence your own creativity?

They are important, I guess, but I’m not that kind of person. I work on my own. I’m quite anti-social. (Laughs.)