How Many Designers Does It Take to Change a Light Bulb?: Samuel Wilkinson

Texte par Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suisse

20.08.11

When young British designer Samuel Wilkinson set out to redesign the standard low-energy light bulb, with the aim of making it work just as hard aesthetically as it does environmentally, he was in for a long trek. Journeying beyond the safe and familiar territory of the archetype is seldom easy, particularly when you have to develop a new set of manufacturing methods to realise your product. In conversation with Architonic, Wilkinson sheds some light on his award-winning 'Plumen 001' bulb.

There are certain object types that have a kind of 'naturalness' about them, a taken-for-grantedness, so ubiquitous are they or long-standing. The incandescent light bulb is one of these. Ask someone to sketch one for you and you're more than likely to end up with the familiar round glass form that narrows at the bottom (or top, depending on which way up you're visualising it) to form its metal contact.

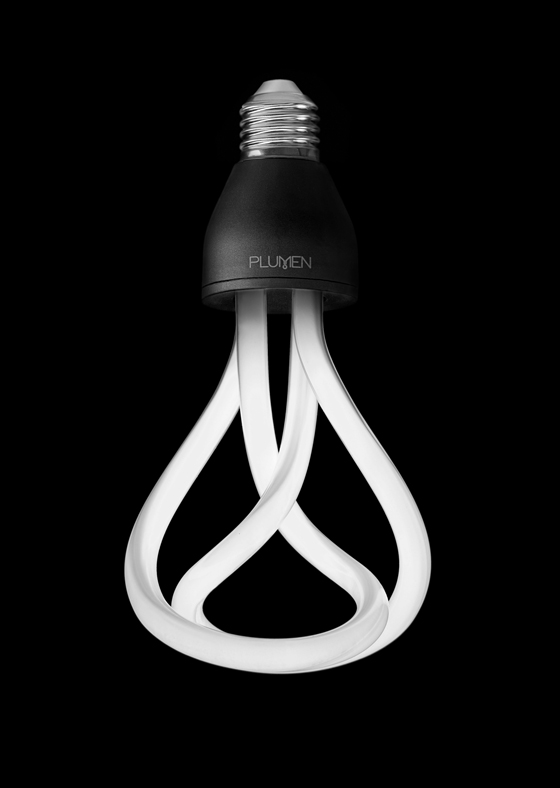

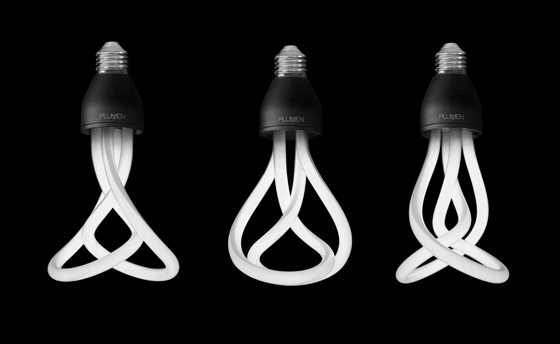

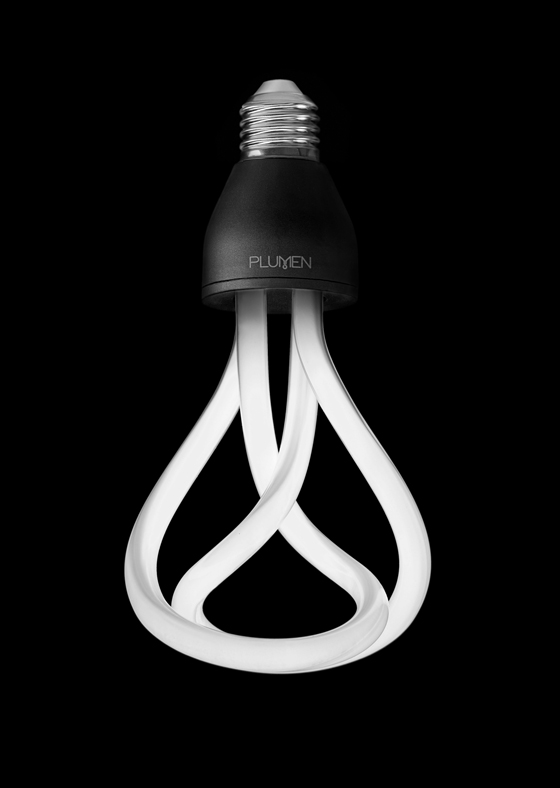

Young British designer Samuel Wilkinson's low-energy 'Plumen 001' light bulb (developed in collaboration with Hulger), whose innovative design earned it the accolade Brit Insurance Design of the Year 2011; photo Andrew Penketh

Young British designer Samuel Wilkinson's low-energy 'Plumen 001' light bulb (developed in collaboration with Hulger), whose innovative design earned it the accolade Brit Insurance Design of the Year 2011; photo Andrew Penketh

×Perhaps design is at its most meaningful when it's deployed to challenge the inevitability of archetypes, replacing the script of 'This is the way it is' with 'Why does it need to be this way?'. Young British designer Sam Wilkinson, whose aesthetically charged 'Plumen 001' low-energy light bulb (developed in collaboration with Hulger) scooped the covetable Design Museum's Design of the Year 2011 award, is an enthusiastic writer of such scripts. 'To work on a project that has the potential to be a real game-changer is always an interesting challenge,' the London-based creative tells Architonic.

'I think you have to survive in this industry. It’s certainly not the easiest ways to make a living but can be amazingly rewarding when it starts to work': Samuel Wilkinson

'I think you have to survive in this industry. It’s certainly not the easiest ways to make a living but can be amazingly rewarding when it starts to work': Samuel Wilkinson

×Wilkinson, whose light bulb restores a certain formal beauty to the object that was lost when the standard CFL bulb came to replace its tungsten predecessor, learned, however, that there's no fast-track to true innovation. While it might be apparent what the destination is, the journey is often somewhat less clearly signposted, with some difficult terrain to negotiate. In the genesis of the 'Plumen 001', it wasn't only the bulb itself that needed to be designed. It became apparent to the designer early on in the project that new manufacturing methods would have to be developed to enable its coming into being.

Architonic caught up Wilkinson to discuss his feted light bulb, as well as to consider the ethical and social responsibilities of the product designer and the true value of design awards.

The 'Plumen 001', with its emphasis on virtuosity of form, makes the low-energy light bulb work as hard aesthetically as it does environmentally; Andrew Penketh

The 'Plumen 001', with its emphasis on virtuosity of form, makes the low-energy light bulb work as hard aesthetically as it does environmentally; Andrew Penketh

×....

Why did you design the 'Plumen' lightbulb? Why do we need it?

The opportunity to design the 'Plumen 001' came up when I met with Hulger at the start of 2009. They presented their idea of a ‘designer, low-energy CFL lightbulb’. The idea was something that resonated with me and to work on a project that has the potential to be a real game-changer is always an interesting challenge.

Low-energy lighting had a bad reputation as being something that you were forced to use, rather than through pure desire. The standard incandescent bulb has a simple beauty, but the standard CFLs appear as if designed by an engineer, lacking the ‘soul’ of the original. So, there was a clear opportunity to really add value.

Wilkinson's limited-edition 'Vessels' series for UK manufacturer Decode, designed especially to house the 'Plumen 001' bulb, is being developed into a production series, to be launched in September during this year's London Design Festival

Wilkinson's limited-edition 'Vessels' series for UK manufacturer Decode, designed especially to house the 'Plumen 001' bulb, is being developed into a production series, to be launched in September during this year's London Design Festival

×How long did the project take and what were the challenges involved?

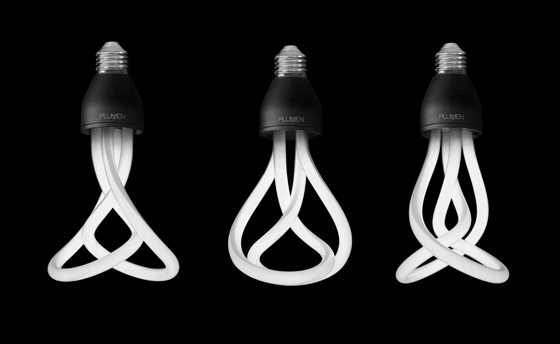

The project took two and half years to launch from first meeting Hulger. The difficulties were mainly technical restrictions; it was very much a learning process. The first part of the process was to analyse thoroughly the standard CFL manufacturing process, and it soon became clear that we would have to suggest new manufacturing methods if we were going to radically change the shape.

New production methods had not been explored for this type of object before. It took a year of presenting concepts and them being rejected to arrive at what would be possible to manufacture.

The glass tubes were the biggest challenge; how the tubes are heated and then moulded is quite restrictive. The phosphorescent coating can only be applied in a certain way, so this informed the shape. Another problem with the standard offering of CFLs was the colouring, which generally gives quite a harsh white light. We ended up with a bulb that produces more of a yellow tint, giving off a softer feel while still maintaining a bright, grade-A-rated product.

A further big challenge was finding the right aesthetic, as the bulb had to work by itself and still be able sit well in other fittings. It was a project that was difficult to appreciate when designing, as there was no previous reference for comparison. This meant you really had to trust your instincts to find the right aesthetic. For the final design, it was important to get a shape that had an organised complexity. By this I mean something that can at first appear quite random, but then, as you move around it, becomes more rational and recognisable.

A contract-space application of Wilkinson's 'Plumen 001' light bulbs; photo Tom Mannion

How would you define sustainability?

My definition of sustainability in design is quality and durability. The quality, long-lasting product is more often more sustainable than a product that functions for a shorter time and is then thrown away, recycled and remade.

Other principles, like energy efficiency, are important, whether in function or by clever and simple construction, thus reducing manufacturing energy. Recycling is also essential, especially in large-scale production, but the term ‘recycled’ can often be oversold for marketing purposes and not backed up by fully encompassing this approach.

What are the social and ethical responsibilities of a designer, in your opinion?

As a product designer, there is a responsibility to educate yourself in social and ethical issues.

Its important to try, as much as possible, to input elements that promote areas such as accessibility, usability, and the environment.

Manufacturers are the ones who shoulder the most responsibility, as they are the ones that have the final say on whether something will go into production. I have been lucky enough to work on a few interesting projects that are really progressive. It’s exciting to work with clients who have vision and are willing to take a risk.

Part of the challenge was, as Wilkinson explains, to find 'the right aesthetic, as the bulb had to work by itself and still be able sit well in other fittings'; photo Tom Mannion

Part of the challenge was, as Wilkinson explains, to find 'the right aesthetic, as the bulb had to work by itself and still be able sit well in other fittings'; photo Tom Mannion

×Put the following in order of importance and explain the reasons for your hierarchy:

Aesthetics, utilitarian function, rhetorical/discursive function, cost, sustainability.

It is impossible to place these in a consistent hierarchy, as each project may start from a different stand point. Fundamentally, I will always try to marry function and form to the highest level. Cost and sustainability are filters through which a concept can be passed repeatedly to assess where it stands.

Currently, I have a few more specific projects that have sustainability at the core. Also working on projects that talk about wider issues, rather than just the object itself, is very motivating.

What would your dream project be?

To design a hotel, the interior, furniture and fittings. That would be amazing.

Who would you most like to collaborate with (either an individual or a manufacturer) and why?

It would be great to work with some top furniture manufacturers, such as Vitra, Flos or Magis, and be given a little more room to explore some different territories. On the other hand, it would be great to work with people in different disciplines, such as the sciences, to collaborate on new materials and processes.

'New production methods had not been explored for this type of object before. It took a year of presenting concepts and them being rejected to arrive at what would be possible to manufacture'; photo Tom Mannion

'New production methods had not been explored for this type of object before. It took a year of presenting concepts and them being rejected to arrive at what would be possible to manufacture'; photo Tom Mannion

×Why do you do what you do?

I love what I do. I think you have to survive in this industry. It’s certainly not the easiest ways to make a living but can be amazingly rewarding when it starts to work. I am really at the start of my career, although I have gained a lot of experience there are always many more things to learn and try to improve upon.

What would you have been if you weren't a designer?

Maybe a scientist. I really enjoyed science and mathematics at school. I always knew I had to do something ‘creative’, as I was never particularly good at the written subjects. The fundamentals are similar, deconstructing previous thoughts on a problem then trying to formulate your own improved ideas.

Are design award schemes important, or are they unnecessary marketing devices?

Some of the big design awards are pure marketing devices. You pay to enter and then pay even more to collect the prize. This means they're really only available to companies that have a sizeable marketing budget to promote a product.

Others awards can be more valid, where you are nominated by selected industry experts and you have no idea that you get nominated. These are more important and are gratifying if you do well.

....