'It's all about surprising yourself': Matthew Hilton at the London Design Festival

Texte par Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suisse

13.10.10

British furniture designer Matthew Hilton's work manages to walk that very fine line between restraint and expressiveness. It's probably why his designs, offering as they do a kind of reassurance, are so respected by so many. But the path hasn't always been a smooth one, as Architonic discovered when we met up with Hilton at this year's London Design Festival.

Those of you who like your music somewhat on the minimal side will probably know contemporary composer Steve Reich's 'Different Trains', a hypnotic piece where a string quartet at times dovetails, at times spars melodically with sampled human voices, creating a multilayered, complex work that assails the listener with its repetitive insistence. It's anything but easy listening.

British furniture designer Matthew Hilton: 'It's nice to show the things you've been slaving away on. It's part of the reward.'

British furniture designer Matthew Hilton: 'It's nice to show the things you've been slaving away on. It's part of the reward.'

×'Different Trains' is also the working title for a new storage piece created by British designer Matthew Hilton, presented for the first time during the recent London Design Festival. While the unit also displays a certainly constructional complexity, it offers, as is typical of Hilton's work with its consideration and emphasis on the well-made, an immediate sense of reassurance. And complex, at least in terms of personality, the designer himself is anything but. You'd be hard pushed to find a more friendly, more open person working in the design industry.

I met up with Hilton at the Tramshed, a pop-up exhibition space in London's Hoxton/Shoreditch district, initiated by high-end Portuguese design brand De La Espada, where his new furniture designs, 'Different Trains' among them, were shown alongside recent work by, among others, Ilse Crawford, Autobahn and Leif.designpark. Here, Hilton spoke thoughtfully and candidly about past production difficulties, future creative challenges and why he finds buying a vacuum cleaner so problematic.

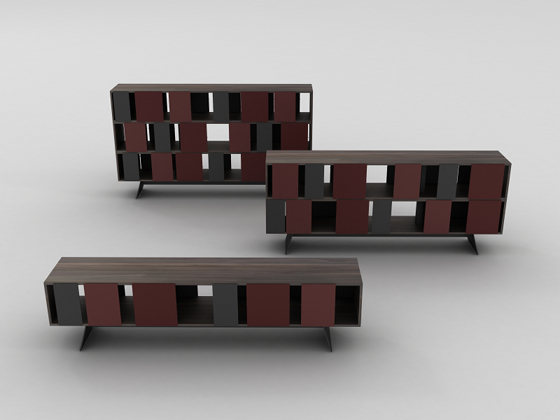

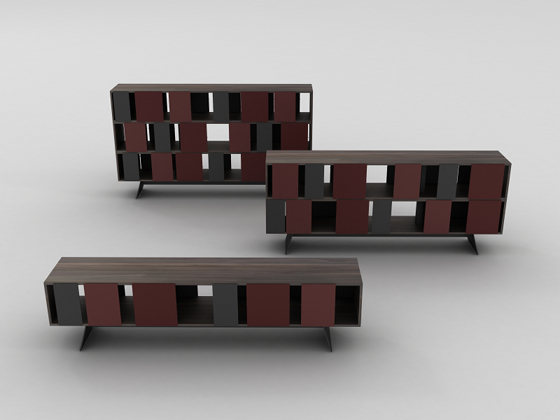

The latest additions to Matthew Hilton's furniture collection, due for production by quality-focused Portuguese manufacturer De La Espada, shown at the Tramshed during this year's London Design Festival

The latest additions to Matthew Hilton's furniture collection, due for production by quality-focused Portuguese manufacturer De La Espada, shown at the Tramshed during this year's London Design Festival

×…..

Do you like showing in these kinds of pop-up venues?

This is lovely, this one. I generally like showing my work. It's nice to show the things you've been slaving away on. It's part of the reward.

Why did you design these new pieces?

Well, we needed to have some storage in the collection. That's the first reason. I haven't got a name for the storage yet, though. I'm thinking about calling it 'Different Trains' after the Steve Reich composition. But maybe it's too long a name.

What would the rationale be for calling it that?

Well, because these elements slide up and down rails. It's a funny thing. It doesn't describe the piece in a literal way. From that point of view, it's not very good, I guess. But once a name sticks, it doesn't really matter.

There's something comfortingly modernist about the piece, the way it plays with volume, with voids. Light and shadow, too. And the sliding movement of the façade elements is beautiful.

Yes. It's a very simple, little plastic fitting that goes on the back.

Matthew Hilton's new sliding-panelled storage piece, 'Different Trains'

So, why did you decide to collaborate with De La Espada?

When I launched my own brand in 2007, I had a lot of things sorted out, but the production and logistics, the selling and distribution hadn't really been addressed. I got a very sharp lesson about that when I made my order, after developing stuff very carefully in Sri Lanka, going through a whole development process, going over there five times. My first shipment arrived two weeks late, which was on the evening before the show. I had to drive to the docks, unpack the container, put the stuff in a van, drive back to the show, get extra time so we could put the stuff on the stand, and then when we opened the packaging the products weren't good enough. They were different here and there to what we had agreed was going to be done. It was just a disaster. Really horrible.

And I had to finance the whole thing. I'd saved money, had to borrow money on my house. Booked a stand at 100% Design, which is a significant amount of money. Done all the PR. All those things. And I had this stuff that was substandard. It was a really difficult time.

The design of 'Different Trains' allows vertical modularity, through the stacking of its basic horizontal form

The design of 'Different Trains' allows vertical modularity, through the stacking of its basic horizontal form

×It sounds like an anxiety dream.

It was horrible. I spent days explaining to people what had happened, that I'd take their card but I wasn't ready to supply. But on the third day, (company founder) Luis de Oliviera from De La Espada walked onto the stand and asked if we could talk about them making furniture for me. I vaguely knew they made expensive products selling in Sloane Avenue, but I hadn't thought about them as a manufacturer. They were another brand. It's like going to B&B Italia and asking them to make products for you. I'd been going round factories and asking them. But Luis approaches this business in a very unconventional way. He talks to competitors about making furniture for them. He builds all these collaborations. It's a fresh approach, which is great.

At first, I felt like I didn't want to give anything away. But I spent a good three months talking to him, thinking about it and finally decided it would be stupid of me not to do it because it was going to sort out all my difficulties. So in 2008 we showed the first five or six products in Milan made by them. And it started from there.

How involved are you during that production process, given the trauma of your experience with the previous supplier, having been laid bare like that in such a public way?

It's a very collaborative process. I'm in charge of how I build the collection strategically. Which pieces do I make, which areas do I work in. I make those choices. I design what I want to design. I then show Luis. Generally he makes very little comment. Although his wife is more vociferous. Which is great. And other people in the company are, too. Then I'm very involved in prototyping and development in the factories. At the time of development, I go to Portugal once every couple of weeks and stay there three or four days and develop with the people who are making things.

That part of the design process, where our drawings are turned into real objects, it's really important to be involved in that. There's a negotiation that has to happen. What we thought was possible and what is really possible. We have to understand the reasons for why something isn't possible or difficult or more costly and adapt the design to suit.

The design isn't finished until you have a finished product. That development process is 20% of the whole process and I don't want to leave that to someone else.

Hilton's new 'Hide' chair, to be produced by De La Espada

Your new work here is being shown under the exhibition banner of 'Human Made', 'emotional design that communicates with the end user', as De La Espada's promotional copy puts it. What does that mean to you?

Working in this kind of collaborative way is where I'm most free to explore my creativity, the kind of things I really want to make. I work in other areas that are more commercially led and are more about price, consumer demand and things like that. This is much more of a personal expression of the things I want to surround myself with. From that point of view it's emotional. I rely a lot on my instinct. What I feel I want to make.

The initial idea and I how I judge the work as we're doing it is an instinctual thing. It's mixed with the intellectual analysis of cost and function. But mostly it's about whether I like something.

Are you designing for yourself?

Not completely. I'm trying to design the kinds of things I would like to buy. But it's not a selfish expression. A design for me doesn't succeed unless it's functioning properly. And answering some kind of need. So I need to know what people want. And so I put myself in the position of other people.

Light on its feet: Matthew Hilton's new 'Light' extendable table

Is one of those needs an emotional one, a function that exists beyond the practical or utilitarian?

There's always an emotional response to the things that you see. The things that you put in your home, that you surround yourself with, you see them every day. Your friends see them, are impressed by them if that's the kind of life you lead. They are saying things about the person who buys them. For people to invest in this level of quality of making and the expense of this kind of furniture, they have to have an emotional kind of response. They make a decision to buy it because they like it. Then comes whether it's comfortable, it works or it fits our house. It's both. I'm not making art, making something that's there to signal your cultural background. Furniture has to perform it's intended function properly.

What's the relationship for you between craftsmanship and that kind of emotional connection?

I have always been interested in the way things are made, that quality of craftsmanship or good making. I'd much prefer to carefully select exactly the right thing to have in my life than chose 20 things, shotgun-style. I have a coffee maker that I bought in 1981, two years after it was designed. By Richard Sapper for Alessi. Stainless steel. Beautiful. And I've had it ever since. And I still love it. It's scratched and there's a dent in the corner. I love having things like that around.

Design that's anti-fashion, I suppose.

Well, there's always that style cycle. But very-good-quality things have a longer life stylistically, because of the investment you put in as an owner. I remember having that coffee maker in my flat in Whitechapel when I was freezing cold the whole time. It's been everywhere with me. It's a silly little thing, but, then again, it isn't. It's like the clothes you wear. For me, just buying a t-shirt is difficult. I have to think about it.

The 'Manta' chair, designed by Matthew Hilton for De La Espada

You're not the only one. I think that a lot of that is to do with a surfeit of so-called consumer choice and the rate at which products are manufactured.

Going shopping for something like a vacuum cleaner I find quite depressing. You look at all the choice, and you end up buying the one that everybody else has, that does what it is supposed to do, works well, doesn't break and looks good. And which probably costs more.

Well, you hope it's going to be a long-term companion.

Well, it's part of your life.

Could you see yourself establishing a relationship with a British design manufacturer?

If there were a good one. Well, there are a few. Very few, though. Ercol is one.

Why are there so few? Britain seems to have the creative talent, but doesn't have the wherewithal in terms of production. This goes back to what you were saying about design being the whole process, right through to the finished product.

Something finished our manufacturing in the last thirty years or so. We became too expensive probably. Somebody thought it was a good idea that we all man call centres instead of... (Laughs.) For a long time in Britain you couldn't get modern furniture made without going through a whole conversation along the lines of 'This is going to be difficult to make, it's going to be expensive and the market doesn't want it.' Everyone was obsessed with the idea that you couldn't sell modern furniture here, that nobody wanted it. It might have been true. But around of the rest of Europe, people were starting to wake up to modern design. I think the timing of the public realising that modern products didn't mean rubbish, that it could be interesting, that realisation came rather late for British industry.

Hilton's 'Tapas' dining chair receives the upholstered treatment

And we are living with the effects of that late realisation.

We don't have any large-scale furniture manufacturing here anymore. Probably the only way that most European manufacturers can survive now is by aiming at a niche. By making smaller numbers of higher priced products.

What are you planning to do next?

I've got to keep working on this collection so that it fills out and answers more needs in the home. So I'm planning floor coverings, lighting, ceramics. I need to grow the collection to a point where it has more body. Then I need to edit, to revisit things and redesign some things.

Are some of those new areas in the collection going to be more challenging for you than others, where you'll be learning something new?

Lighting. I don't know a lot about lighting. But the challenge with the furniture is to do something fresh and personal, so I have to push myself there creatively. But technically, lighting is going to be the challenge. The other thing is rugs and floor coverings, because I know nothing about them really. I have an idea about the type of thing I want to produce but I need to find out where they can be made. Similarly with ceramics. I have an idea about that. There's a technique that I saw in Turkey or Morocco where they make little tiles, all hexagonal, almost like seaside rock – they lay lots of different colours together in a long form and slice them off. I'd like to use these tiles to make things.

It's all about surprising yourself. Pushing yourself.

Thanks very much for your time, Matthew.

.....