New Éire: Ireland's modernist self-fashioning revisited

Texte par Simon Keane-Cowell

Zürich, Suisse

14.01.11

Ireland is in a reflective mood these days. With the island nation on the edge of Europe facing up to the reality of a severely damaged economy and a decimated construction industry, nostalgia is doing what it's wont to do.

Any discussion of architecture in an Irish context is somewhat of a sensitive issue at the moment.

A decade and a half of exhilarating economic growth in the Republic of Ireland came to spectacular end in 2008, when the country had the unfortunate honour of being the first member state of the European Union to enter into recession. And enter is putting it lightly. Plunge might be a more fitting way to describe it. Three years and one IMF bail-out later, and an general election round the corner that will undoubtedly see the incumbent government dramatically kicked out of office for their perceived mismanagement of the economic crisis, and things are looking bleak for the island nation.

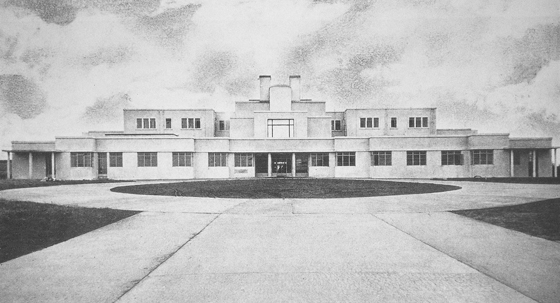

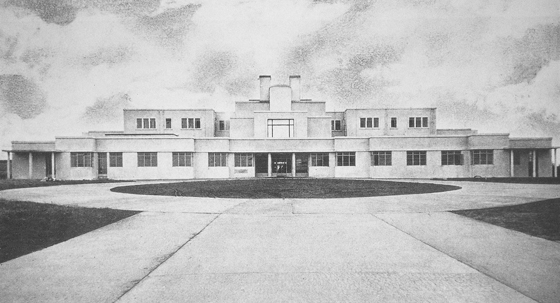

Desmond Fitzgerald and the Office of Public Works' modernist Gesamtkunstwerk, Dublin Airport, completed in 1940; photograph by Hugh Doran, 1954, Hugh Doran Collection, Irish Architectural Archive; image courtesy of Irish Museum of Modern Art

Desmond Fitzgerald and the Office of Public Works' modernist Gesamtkunstwerk, Dublin Airport, completed in 1940; photograph by Hugh Doran, 1954, Hugh Doran Collection, Irish Architectural Archive; image courtesy of Irish Museum of Modern Art

×With some commentators suggesting that up to 40% per cent of the country's GDP at the height of the boom years was bound up with the construction industry (the expression 'Don't put all your eggs in one basket' comes to mind), it's not a case of hyperbole to suggest that the architectural industry has been decimated. Years of easy credit, fuelled by low interest rates, created the mother of all property bubbles, the detritus of which, post-bursting, can be seen in the static cranes and abandoned building sites of Dublin and beyond.

Swan song? Daniel Libekind's highly expressive Grand Canal Theatre, situated in Dublin's regenerated docklands area, might be, given Ireland's new economic straits, the country's last 'grand projet' for the foreseeable future; photograph by Ros Kavanagh

Swan song? Daniel Libekind's highly expressive Grand Canal Theatre, situated in Dublin's regenerated docklands area, might be, given Ireland's new economic straits, the country's last 'grand projet' for the foreseeable future; photograph by Ros Kavanagh

×Grand Canal Theatre, designed by Daniel Libeskind and completed in 2010, helps to delineate a new public space, Grand Canal Square, itself part of what was an ongoing redevelopment of Dublin's old docklands area; photograph by Ros Kavanagh

Grand Canal Theatre, designed by Daniel Libeskind and completed in 2010, helps to delineate a new public space, Grand Canal Square, itself part of what was an ongoing redevelopment of Dublin's old docklands area; photograph by Ros Kavanagh

×Yet it all makes sense in psychological terms. The Irish, like the British, love to own their own home. And, somewhat perversely, the more expensive property becomes, the greater the desire to be a member of the home-owning classes. The notion of property as a index of security, of social status, becomes all the more important in a country like Ireland, however, when you remember that the new-found wealth of the early 1990s onwards followed decades of, in a European context at least, relative economic disadvantage. Why not feather your nest now that you've got some cash in your pocket? Indeed, why not buy a second, or even third, nest? In architectural terms, this often meant, sadly, poorly designed apartment buildings in cities or sprawling estates on the edges of towns. Meanwhile, the countryside became populated with single-storey, breeze-block-built houses, which, while easy to finance and easy to construct, but which showed little evidence of a dialogue with their surroundings. 'Bungalow blight' is how this phenomenon has been described by some.

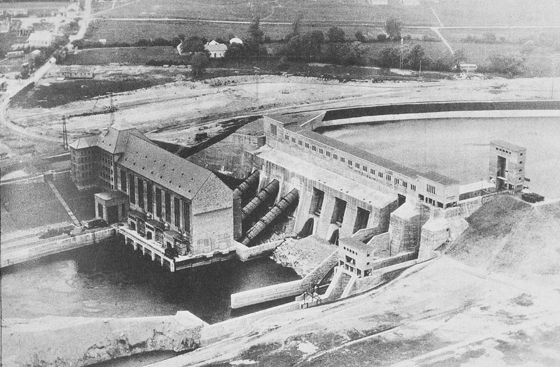

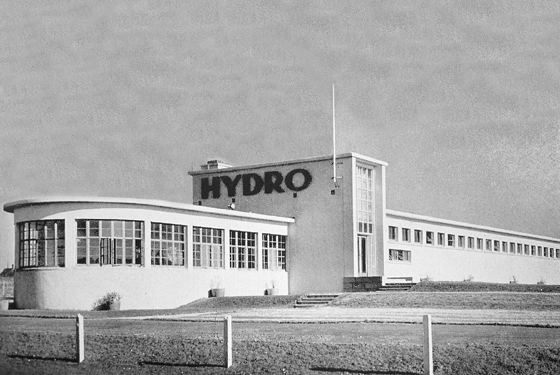

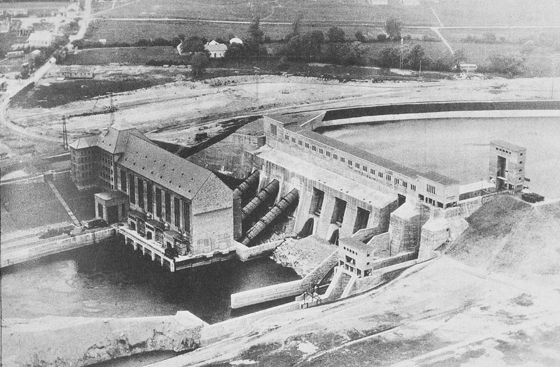

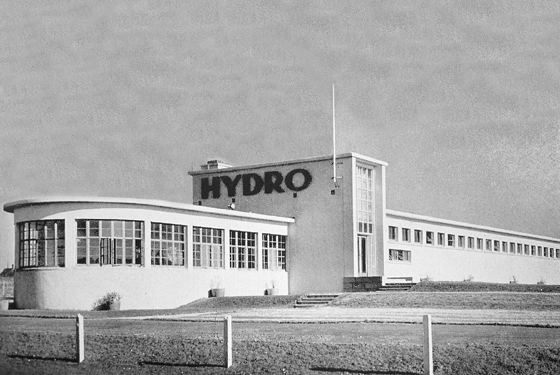

German-designed, Irish-built. The new Irish Free State's first large-scale public-works project, the hydroelectric power station and dam at Ardnacrusha, completed in 1929. Here, real power comes to symbolise the political power of the fledgling nation *

German-designed, Irish-built. The new Irish Free State's first large-scale public-works project, the hydroelectric power station and dam at Ardnacrusha, completed in 1929. Here, real power comes to symbolise the political power of the fledgling nation *

×And yet Ireland, in spite of this recent rush to build, often quickly and cheaply, features examples, both contemporary and historic, of architecture that is creatively considered and well executed. The recent completion of Daniel Libeskind's highly expressive Grand Canal Theatre, which forms one aspect of the newly created Grand Canal Square public space, itself part of the development of Dublin's former docklands, is probably the last 'grand projet' that the country will see for a while, but if this is the case, there could be worse buildings to bow out with.

Completed in 1940, Desmond Fitzgerald's high-modernist Dublin Airport building speaks, in its architectural language, of a different kind of transport – the ocean-going liner *

Completed in 1940, Desmond Fitzgerald's high-modernist Dublin Airport building speaks, in its architectural language, of a different kind of transport – the ocean-going liner *

×It may be because of the current state of economic and political affairs (nostalgia will, it seems, always have its way at times like this), but the much under-analysed strand of modernism in Irish architecture, and in design also, in the first half of the 20th century is the subject, in part, of an exhibition running currently at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, and of a recently published book entitled 'Free State Architecture' (Gandon Editions), which examines the surprisingly convincing, but internationally obscure, body of resolutely modernist work created in Ireland following the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922 up to the declaration of Ireland as a republic in 1949.

Leading proponent of modernism in Irish architecture Michael Scott's Busáras bus terminal and office building in Dublin, completed in 1953 *

Leading proponent of modernism in Irish architecture Michael Scott's Busáras bus terminal and office building in Dublin, completed in 1953 *

×If part of the Modern Movement's aim, with all of its social and political investment, was to privilege the functional over the meaninglesly stylistic, and, in doing so, attempt to remove historical reference from design in the creation of a rational formal language, then it's easy to understand why a new nation, keen to distance itself from its past, would want to draw on such a supposedly democratic design rhetoric. The new nation chose what was later to develop into the International Style as the means of expression for the ambitious programme of modernisation it set itself, which ranged from transport and health provision to electrification, and, in tandem with this literal construction, sought to build an image of itself, for consumption both domestically and abroad, of the state as a modern one. No mean feat in a country whose economy was, at the time, predominantly based on agriculture and which had not experienced an industrial revolution to speak of. (The only industrialised city on the island – Belfast – was separated from the Irish Free State in the partition of 1921, becoming part of Northern Ireland.)

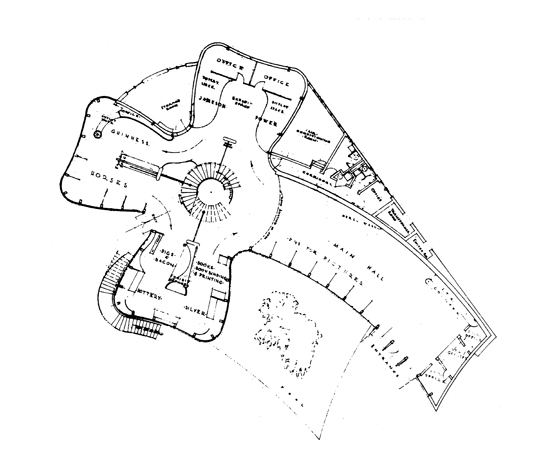

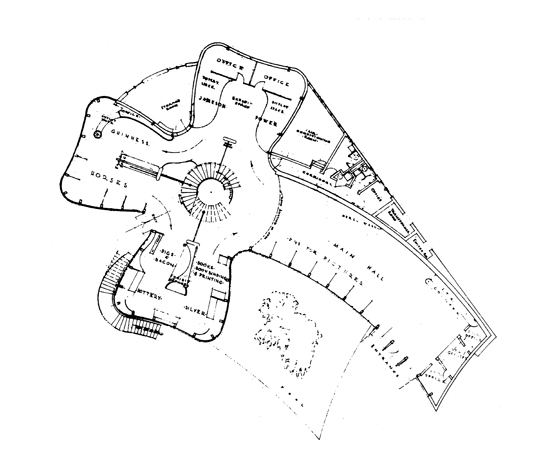

Ireland's first apearance on the international exhibitionary stage at the 1939 New York World's Fair saw Michael Scott deliver the ultra-modern Irish Pavilion, complete with externally mounted sculpture of 'Mother Éire' and type by Eric Gill *

Ireland's first apearance on the international exhibitionary stage at the 1939 New York World's Fair saw Michael Scott deliver the ultra-modern Irish Pavilion, complete with externally mounted sculpture of 'Mother Éire' and type by Eric Gill *

×Viewed today as possibly somewhat ham-fisted, Michael Scott's Irish Pavilion for the 1939 New York World's fair represented the Irish shamrock in plan *

Viewed today as possibly somewhat ham-fisted, Michael Scott's Irish Pavilion for the 1939 New York World's fair represented the Irish shamrock in plan *

×One of the first departures from conventional architectural historicism in Ireland, which functioned as an act of national muscle-flexing as much as serving a specific utilitarian purpose, was the Shannon hydroelectric power station and dam at Ardnacrusha, Co Clare, completed in 1929. Designed by the German engineering firm Siemens-Schuckert, and reminiscent, with its long vertical fenestration and overall scale, of Peter Behren's iconic 1910 AEG factory in Berlin, the effect of this project on people's lives in terms of providing electricity for the first time to many rural communities cannot be under-estimated. That said, the project also performed an international function. The creation of Ardnacrusha, with its literal generation of power, was designed to operate symbolically, too, the project functioning as a symbol abroad of the recently founded state's new political power and self-determination.

Inside Michael Scott's Irish Pavilion, with its fully glazed curtain walls, visitors were presented with a mural of the Irish Free State's earlier nation-building project, the hydroelectric power station and dam at Ardnacrusha *

Inside Michael Scott's Irish Pavilion, with its fully glazed curtain walls, visitors were presented with a mural of the Irish Free State's earlier nation-building project, the hydroelectric power station and dam at Ardnacrusha *

×Nation-building was clearly a priority in the creation of Dublin Airport's emphatically modernist terminal building of 1940, too, designed by the state-run Office of Public Works, under the direction of Desmond Fitzgerald. With its curved plan, ribbon windows, cantilevered balconies and continuous horizontal railings, the 'Gesamtkunstwerk' of a structure is, ironically, suggestive of a different form of transport – the ocean-going liner – and announces to passengers the country's modern credentials, or, at least, its aspirational modernity.

'Geragh', the house Michael Scott designed for himself on the edge of Dublin Bay (1937–38), served a highly visible sign of the architect's commitment to modernism *

'Geragh', the house Michael Scott designed for himself on the edge of Dublin Bay (1937–38), served a highly visible sign of the architect's commitment to modernism *

×Such was the perceived level of sophistication of the building by the public, that, parallel to its use as a transport hub, it also served, with its restaurant, sprung dance-floor and viewing platform, as a destination in itself for pleasure-seeking Dubliners. In spite of the grand gesture of the building's modernist architecture, however, the project's potential international recognition became a hostage to historic fortune, as the outbreak of the Second World War ushered in a level of censorship that prevented Fitzgerald's building from being widely publicised.

Power to the people: the Dublin Gas Showroom (top, 1930) on D'Olier Street and the Transformer Station (bottom, 1929) on Fleet Street, two Dublin structures that show the application of an Art Deco-oriented modern style to energy-related buildings *

Power to the people: the Dublin Gas Showroom (top, 1930) on D'Olier Street and the Transformer Station (bottom, 1929) on Fleet Street, two Dublin structures that show the application of an Art Deco-oriented modern style to energy-related buildings *

×Alongside Fitzgerald in the league of architects who helped develop a new, modernist architectural language in Ireland is Michael Scott. Indeed, he probably ranks as its most fluent speaker. Not only did he design Busáras (completed in 1953), Dublin's national bus terminal and integrated office building, which, with its distinctive ziggurat reinforced-concrete canopy and playful use of faience and mosaic, threw a contemporary cat among the traditional pigeons, sitting as it does between Georgian Dublin and the city's neoclassical landmark Custom House, he was also responsible for a memorable piece of architectural nation-making – the Irish Pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair in New York. What may need now seem a rather ham-fisted attempt to transpose a long-standing graphic symbol of nationhood into an architectural scheme – the temporary structure's plan takes the form of a shamrock – has to be understood in a specific historical context. The New York exhibition was the first time the fledgling Irish state presented itself as an independent nation at an international affair, so the stakes were high.

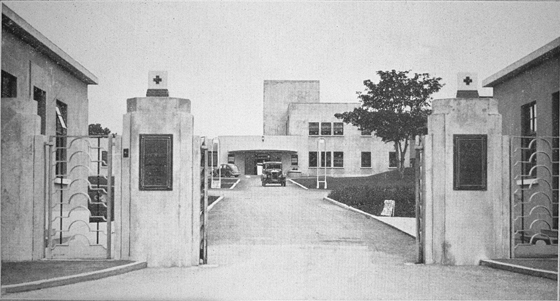

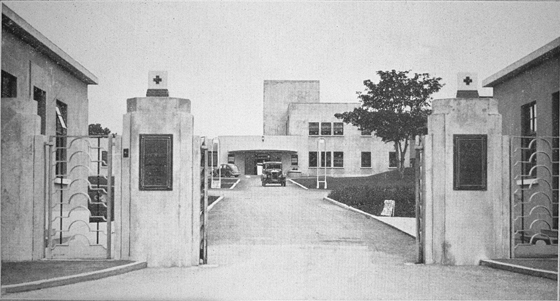

A central part of the new Irish nation's provision of public services was the building of new hospitals. Here, modernism finds expression in Nenagh General Hospital (top, 1933–36) and Portlaoise County Hospital (bottom, 1933–40) *

A central part of the new Irish nation's provision of public services was the building of new hospitals. Here, modernism finds expression in Nenagh General Hospital (top, 1933–36) and Portlaoise County Hospital (bottom, 1933–40) *

×Despite the contrivance of the pavilion's national-symbolic function, as a building it was highly considered in its rationalism. Its curvilinearity, married with fully glazed curtain walls, white-painted stucco and a general eschewal of ornament, other than an Friedrich Herkner-designed exterior-mounted sculpture representing Mother Éire and Eric Gill type spelling out 'IRELAND', combined to express a controlled, confident, and, above all, thoroughly modern environment that challenged the country's traditional, historic associations. Inside, a mural by Seán Keating depicted that earlier project of national pride, the hydro-electric power station at Ardnacrusha.

Beyond the Pale: Modernism in Tramore, Co Waterford, in the form of The Hydro, designed by Patrick Sheahan (1946–49) *

Beyond the Pale: Modernism in Tramore, Co Waterford, in the form of The Hydro, designed by Patrick Sheahan (1946–49) *

×At home, too, Michael Scott, was living like a Modern. Possibly one of the most interesting of the small number of private residences to be built in the modernist idiom in Ireland, 'Geragh' (1937–38), the house he designed for himself in Sandycove, just south of Dublin city, features a series of striking curved bays that echo the coastline on which the building sits. And location, here, is as important as the architecture itself. The house's highly prominent geographical position allows it to function as a strong visual declaration of Scott's commitment to the Modern Movement. A manifesto statement, if you will.

Waterloo House lounge bar on Dublin's Upper Baggot Street (1938), designed by Fergus Ryan and Brendan O'Connor, serving drinks to patrons in a modernist style *

Waterloo House lounge bar on Dublin's Upper Baggot Street (1938), designed by Fergus Ryan and Brendan O'Connor, serving drinks to patrons in a modernist style *

×Like the work of Eileen Gray (undoubtedly the most prolific figure in Irish modernist-design history), which only received true critical attention in the late 1960s when 'Domus' magazine published a retrospective piece on the Paris-based designer's career, it is somewhat after the fact that the importance of modernism and the International Style in the Irish architectural landscape is being discussed and celebrated. Better late than never, of course. And, given that the wind that gone out of Ireland's economic sails for the moment, forcing the country to think, in the absence of profligate borrowing, spending and building, what its true values are, what better time to reflect on those architectural projects of the past that sought to say something about the young nation's aspirations to be a modern and democratic society.

Michael, we can still see your house from here.

.....

Further information:

'Free State Architecture: Modern Movement Architecture in Ireland, 1922–1949' by Paul Larmour

Published by Gandon Editions

112 pages

Hardback

ISBN: 978 0948037 726

* Image from 'Free State Architecture: Modern Movement Architecture in Ireland, 1922–1949' by Paul Larmour (Gandon Editions)

'The Moderns' runs at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, until 13 February 2011