Urushi - Japanese Lacquer in modern Design

Texte par Susanne Fritz

Suisse

30.03.12

An important component of the Japanese art of lacquerwork is the special technique known as "urushi", which uses many layers of wafer-thin, semi-transparent lacquer to create a surface of almost mystical radiance and sensual depth.

Stone Implement Bowl by Takeshi Igawa, Polyurethane Foam with Urushi, Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition

Stone Implement Bowl by Takeshi Igawa, Polyurethane Foam with Urushi, Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition

×The word 'urushi' designates both the lacquer itself and the art of Japanese lacquerwork, which represents a tradition going back thousands of years. The special sheen and visual depth of these lacquer surfaces exert a fascination which has inspired modern designers to apply this technique for themselves. However, in the process a number of challenges need to be overcome, because outside of Japan there are few artists who command the techniques of the craft.

Stool Tri pod existing out of 3 elements, Aldo Bakker 2006; size: 340 x 330 x 320 mm; material: Ice blue urushi; urushi execution: Mariko Nishide; urushi supplier: Takuo Matsuzawa, Joboji Urushi Sangyo; photography: Erik en Petra Hesmerg

Stool Tri pod existing out of 3 elements, Aldo Bakker 2006; size: 340 x 330 x 320 mm; material: Ice blue urushi; urushi execution: Mariko Nishide; urushi supplier: Takuo Matsuzawa, Joboji Urushi Sangyo; photography: Erik en Petra Hesmerg

×As a material, urushi is obtained from the sap of the lacquer tree which is a native of south-eastern Asia. Slashes are made in the tree and the sap which seeps out is caught in a container before being filtered several times through a number of layers of special paper. The result is a clear lacquer which ranges in colour from light to dark amber, with any excess water being allowed to evaporate. To the present day urushi is stored in wooden vats which are covered with parchment, but for export purposes urushi is also available in tubes.

Casket with lid by Manfred Schmid, matte urushi lacquer, 18 cm in diameter

Casket with silver lid by Manfred Schmid, 15 cm in diameter

Urushi can be applied to a wide range of backing materials, and neither soaks in immediately nor dries out rapidly as a result of the evaporation of a solvent. Under ideal circumstances urushi sets at high humidity of 75 to 80 per cent and a temperature of 24 degrees. Under these circumstances the polymerisation process of the urushi sets in, which in general terms means that a network of molecules is formed and covers the surface.

Synthetic polymers are as a rule plastics, but thanks to its resistance to water, alcohol, acids, lyes and solvents, as well as a resistance to heat of up to 280 degrees combined with elasticity and mechanical resilience, urushi is superior to most synthetic polymers.

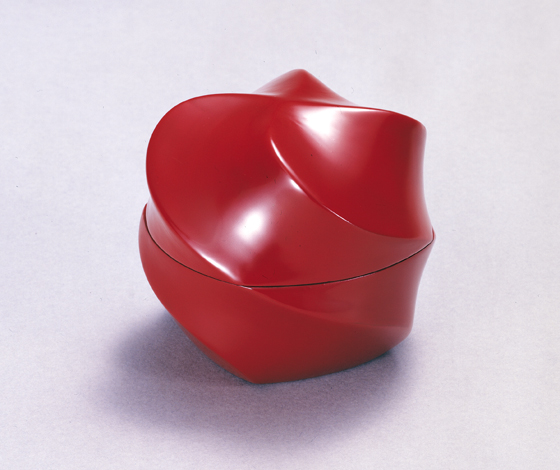

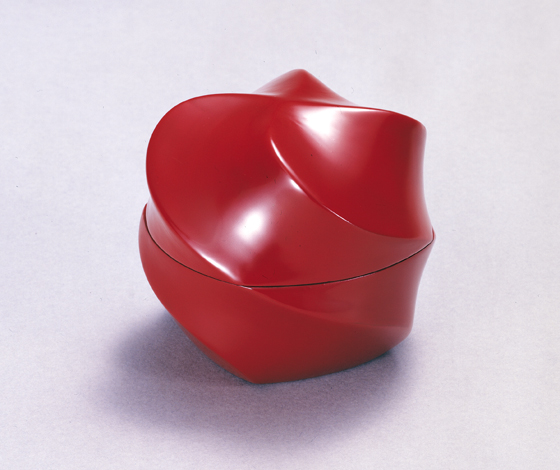

Red laquer urushi casket by Kuroda Tatsuaki (1904–1982)

Traditionally urushi lacquer is applied with a brush made of women's hair. The brush is similar in principle to a flat wooden pencil in that the long hair of Asian women is clamped between two pieces of flat wood. The brush is then shaped by carving off part of the wood and cutting the hair to the required length. There is a practical reason for the use of women's hair, in that Asian hair is smooth and has a special structure of its own - and because Japanese men normally wear their hair short women's hair is the most suitable.

Red laquer urushi casket by Kuroda Tatsuaki (1904–1982)

The origins of lacquerwork in the Orient go back to pre-Christian times, when urushi was used not only as a medium of aesthetic expression but also for practical purposes as a preservative. In the sixth century Buddhist monks reached Japan via Korea, giving new stimulus to the craft of lacquerwork in the country and perfecting urushi art both from a technical and an artistic point of view.

One typical feature of Japanese lacquerwork is the 'sprinkled picture', which reached its artistic zenith in the ninth century A.D. In this art form gold or silver powder is sprinkled through a tube onto a still-moist, generally black lacquered surface.

This technique is being applied in the same way to the present day. The natural colour can be modified by various forms of pigmentation, with red pigmentation created by cinnabar and ferric oxide and black pigmentation created by lamp black or iron powder forming the basic colours of traditional urushi.

Red urushi baby bathtub by Yohko Toda, Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition

In Japan training to become a urushi master is restricted to Japanese or at least Japanese-speaking persons, and as a rule the craft of urushi artist is not open to women.

Several years of training are required in order to become a urushi master. In traditional urushi work the products which are created, their appearance and quality as well as the working methods and the division of work are strictly defined. All these factors have preserved the original values of this traditional craftsmanship. Urushi is a matter of perfection, of luxury in art, whose design has to possess purity. On the other hand, these strict definitions have also restricted the further development of this artistic craft, which like almost all crafts is struggling to survive in the modern world. Accordingly, in order to keep alive urushi craftsmanship the guild of urushi masters in the Japanese province of Ishikawa has opened its doors to new methods and products, and has entered into a dialogue with artists from other countries.

As part of these activities the Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition was established in 1989. The most recent and eighth exhibition in the series was held in 2009 on the theme of “The New Realm of Urushi Ware”.

The exhibition featured 82 works from 11 countries, displaying the new developments in design and artistic possibilities which are offered by this material.

Kenji Ekuan, member of the jury of the Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition, formulates the current situation in this way:

"Japanese people have had trouble in considering elegant and noblelady-like Urushi ware as products perhaps because they have worked hard to manufacture industrial products and sell them to foreign countries for many years since the end of World War II. I wonder if they have pursued the so-called virginity in Urushi ware among numerous other arts and crafts items. It is true that Urushi ware producing regions will be declining unless they make Urushi products which the consumers would like to buy."

Fuki Urushi Table by Frederic Dedelley and Salome Lippuner

The versatility of urushi is demonstrated by some prize-winning objects in the design competition of the Ishikawa International Urushi Exhibition: the first prize was won by Takeshi Igawa with a bowl made of rigid polyurethane foam which was coated with urushi. The Japanese artist designed the 'Stone Implemented Bowl' as early as 2007, a year before graduating from the Kyoto City University of Fine Arts. Another of his works, the 'Leaf Figures' which were created in 2005, shows the traditional technique of kanshitsu in combination with Urushi. Kanshitsu is a very old technique for creating rigid forms with cloth, which in the past was even used to create samurai armour. A basic frame is covered with several layers of linen (mabu) which are coated in lacquer and stuck together with rice lime. When this has dried the underlying frame is removed, leaving behind the living and light shell, the shape of which has been fixed by the lacquer and the lime and which is given a glossy finish by a final coat of urushi lacquer.

RELIGIO - RE-BOUND TO THE SOURCE, Kanshitsu jars by Manfred Schmid

With RELIGIO - RE-BOUND TO THE SOURCE the German urushi artist Manfred Schmid also won a design prize in Ishikawa.

He too worked with the kanshitsu technique of treating cloth with lime and lacquer, but he used his own design principles which are far removed from those of traditional kanshitsu. A roughly sawn polystyrene shape forms the basis for a clay model which deliberately allows for the unevenness of the surface. After the bonding process Religio is not finished with shiny lacquer but is treated on the inside and on the edges with sabi (a mixture of baked Japanese clay and urushi). As a result the objects retain the aesthetic of a rough model, making a more archaic impression than a perfectly finished surface.

Salome Lippuner, a jewellery designer from the Swiss Jura discovered urushi when, on a trip to Japan, she visited the town of Wajima in the prefecture of Ishikawa, a town also referred to as 'Urushi no Sato', the hometown of lacquer. After showing her works, which were created using techniques she has developed for herself, a spiritual dialogue was established and Salome Lippuner became both an apprentice and a strategic advisor who has demonstrated new approaches for the development of this craft. Salome Lippuner is highly regarded internationally as a urushi expert, and is consulted by designers and architects on development and planning, because the quality of urushi lacquer is highly suited to the enhancement of furniture and architectural surfaces. In cooperation with the product designer Frederic Dedelley she has created the "Fuki-Urushi Table" from pine wood. Fuki-urushi is a lacquering technique which brings out the beauty of the wood's structure and highlights its grain. The raw lacquer is applied to the surface of the wood and any excess lacquer is removed with absorbent paper. After the first coat has dried the process is repeated around 15 times. The result is a deep black surface with the grain highlighted by the glossy sheen of the lacquer.

Side table Urushi Series by Aldo Bakker, 2008, material: pink lilac urushi; size: 800 x 550 x 340 mm; urushi execution: Mariko Nishide; photography: Erik and Petra Hesmerg

Side table Urushi Series by Aldo Bakker, 2008, material: pink lilac urushi; size: 800 x 550 x 340 mm; urushi execution: Mariko Nishide; photography: Erik and Petra Hesmerg

×Aldo Bakker regards his urushi objects as a bridge between traditional craftsmanship and industrial manufacturing techniques. Even if nothing could be more different than the master craftsmanship on the one hand and digital precision technology on the other, but both have in common is striving for perfection. The combination of maximum manual craftsmanship skills and computer controlled production methods generates an aesthetic of perfection.

The core made of rigid PU foam provides the shape of the object, which Bakker regards as a dead underlying structure that is brought to life by the 16 coats of urushi lacquer and, thanks to this process of enhancement, even receives a permanent character:

"The ‘Urushi Series’ is primarily about sustainability. My vision of sustainability is mainly directed at influencing behavior. My products represent a peaceful, silent protest against the way that consumer society has increasingly become only about the material. My answer is an effort to create products that are endlessly enduring and that point towards ‘eternal life.’ Conservation versus consumerism."

Le lac, Aldo Bakker 2007, size: 1770 x 1410 x 120 mm; material: Ocean green urushi; urushi execution by Mariko Nishide; photography: Erik and Petra Hesmerg

Le lac, Aldo Bakker 2007, size: 1770 x 1410 x 120 mm; material: Ocean green urushi; urushi execution by Mariko Nishide; photography: Erik and Petra Hesmerg

×Nendo creates a juxtaposition between the quality craftsmanship of urushi and the disposability principle of paper cups for instant noodles. Her "cupnoodle urushi” was created for the Cupnoodles Museum in Yokohama, Japan. Nendo commissioned urushi artists to apply the urushi directly onto the disposable paper cups, thus redefining the worth of this throwaway packaging by subjecting it to a process of enhancement which transforms it into tableware.

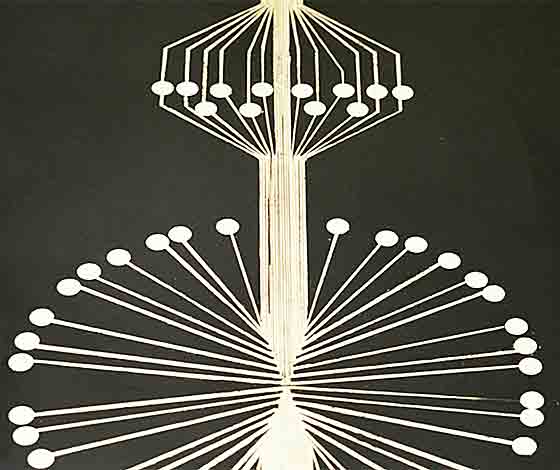

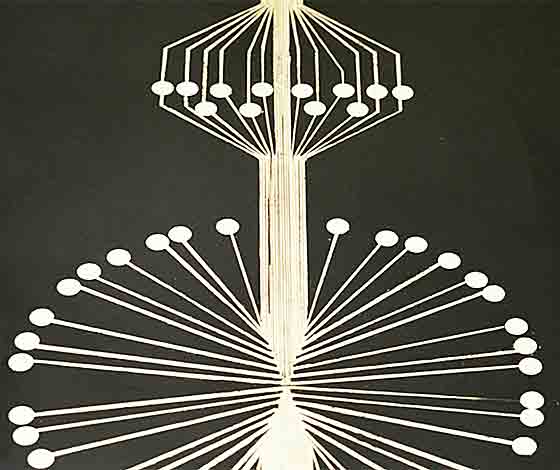

'Urushi musical interface', by Yuri Suzuki, a touch panel style instrument which uses the principle of gold inlay

'Urushi musical interface', by Yuri Suzuki, a touch panel style instrument which uses the principle of gold inlay

×'Urushi musical interface', by Yuri Suzuki, a touch panel style instrument which uses the principle of gold inlay

'Urushi musical interface', by Yuri Suzuki, a touch panel style instrument which uses the principle of gold inlay

×The bridge between old and new leads in both directions: the durability and preservative properties of urushi as well as the traditional virtues of craftsmanship which are connected with urushi such as respect for the material, elaborate high-quality processing and the ethos of workmanship are, in view of the current debate on sustainability, very much a contemporary theme. In return the combination of new materials and a modern formal idiom is reawakening an older and traditional craft to new life.

Accordingly in its turn part of our contemporary design will, under the thousand-year old lacquer of urushi, itself form a bridge to the future.