Getting high in London: the 2012 Olympic city's controversial new tower

Texte par Tim Abrahams

London, Royaume-Uni

22.04.10

When Mayor of London Boris Johnson unveiled the design of a 115-metre-high steel tower by renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor, which is to be built next to the city's new 2012 Olympic Stadium, the reaction from press and public was one of emphatic disapproval. London-based architecture critic Tim Abrahams, voice of the minority, mounts a defence of the 'Orbit'.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, the Church of England's most senior cleric, described it sarcastically as having ‘the supreme merit of serving no useful purpose whatsoever’. Yet the Skylon remains one of the most treasured moments of public art in British history. A long, narrow ellipsis of lattice-worked steel, it was supported and held in position by high-tension wires, becoming the vertical marker for the 1951 Festival of Britain and, eventually, much-loved. A symmetrical tear in the firmament, it rose to a height of 90 metres and expressed the buoyancy and optimism of the post-war event – an emblem that also augured the high-tech aesthetic that would dominate the architectural avant-garde in Britain for the rest of the century. So potent was its evocation of a bold new future that when Winston Churchill – that arch-conservative – was voted back into power in 1952, he ensured it was demolished.

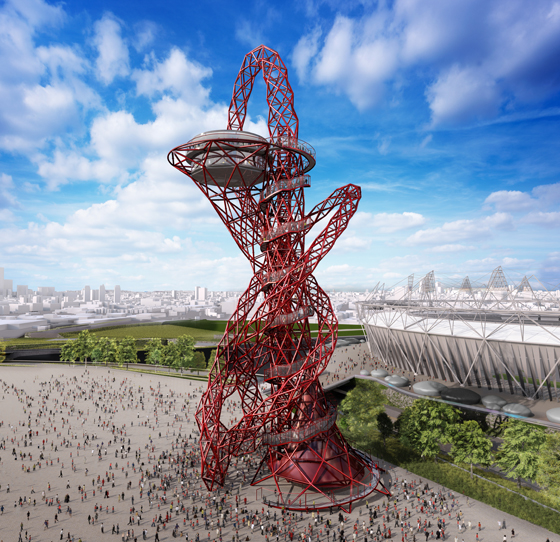

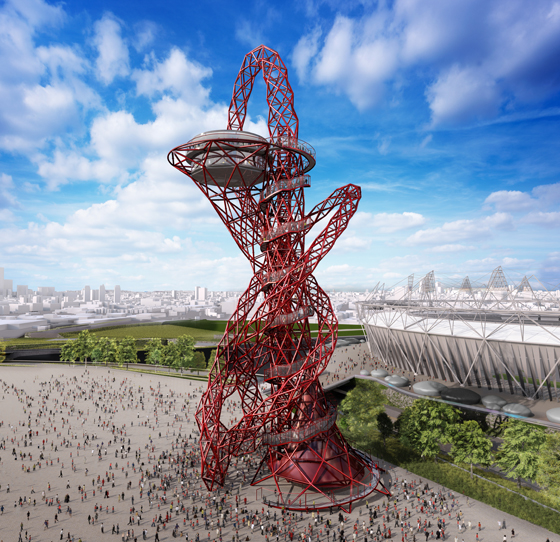

Rendering of the Orbit, designed by artist Anish Kapoor and to be built on London's new 2012 Olympic site

Rendering of the Orbit, designed by artist Anish Kapoor and to be built on London's new 2012 Olympic site

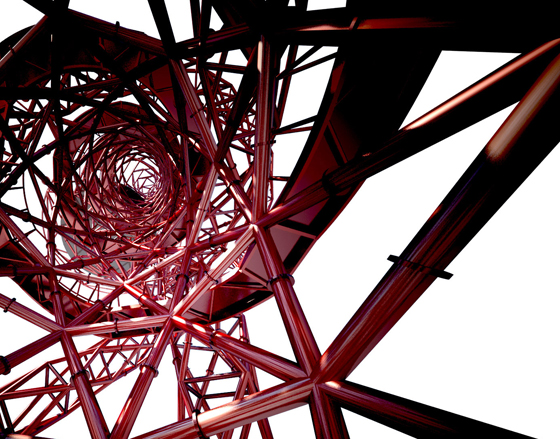

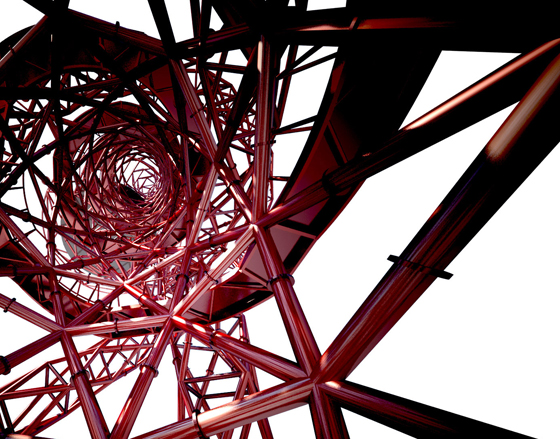

×When the Orbit, the 115-metre-high tower designed by artist Anish Kapoor and engineer Cecil Balmond, was unveiled earlier this month, a chorus of disapproval similarly rose to greet it. Criticism focused primarily on the massive sculpture’s lack of obvious meaning and an apparent difficulty in appreciating the scale of the project, which will stand as a permanent structure immediately adjacent to the Olympic Stadium, built for the 2012 games. At the launch of the tower earlier this month, Kapoor described it as ‘an object that doesn’t have a singular image from any one perspective’ and ‘which requires a journey around the object and … a journey up and through the object’ before it is complete. The British, it would appear, are still adverse to art that doesn’t have an ascribed meaning.

Of course, modern media demands that an image accompany the announcement of any new building. An un-built, three-dimensional experience must, perforce, become a computer-generated, two-dimensional one. And those who are critical of the project have clearly fixated on the CGI of an art object that was created for the press launch by the engineering firm Arup. This renowned practice has certainly helped deliver, with sensitivity and judgment, some extraordinary architecture, but they still have some way to go when it comes to conveying scale, let alone the nuances of a complex sculpture, in a few CGIs. The actual model that Kapoor and Balmond presented was far more intriguing. Here we have a structure that defies easy reading, something you can look at and engage with. Far from simply being unstable, it is supposed to dramatise instability.

Model of the Orbit, unveiled at London press conference in April 2010; photo James O. Jenkins

There is also a very obvious resistance to the notion of a branded piece of sculpture sitting at the heart of the Olympics Park. This has more traction and is something that also explains an underlying resistance to the work, although one that has been expressed in aesthetic rather than political language. Mayor of London Boris Johnson is very much the handmaiden of the ArcelorMittal Orbit (to give it its full brand name), having pushed it onto a recalcitrant Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), who looked set to deliver the Olympic infrastructure before their deadline. Boris was not to be dissuaded by schedules and small budgets, claiming at the sculpture's launch that he buttonholed Lakshmi Mittal, director of the multinational steel manufacturer, in a cloakroom in Davos, Switzerland, last year. 'It's an exaggeration to say it was a 60-second conversation. It was a 45-second conversation,' joked the mayor. The sculpture will be adorned with advertisements to the largesse of the global firm during the Olympics, but this will not be the case afterwards, according to Johnson.

Nor was the manner in which the tower (or rather the rethinking of a tower) was selected a great help in the battle for support. It was launched unexpectedly on the public by the Mayor’s Office. Instead of being procured through an open competition, the design was selected through a closed one and judged by a panel of art grandees with a vested interest. It is more by luck than design that a challenging proposition was selected. Neither politicians nor figures such as Sir Nicholas Serota of the Tate have much of a defence should the project prove to be a failure. Even as lawyers figure out how to circumvent OJEU laws, Johnson and others can only hope that the work is successful in artistic terms. They are fortunate, at least, that the rest of the art on the Olympics Park, which has been commissioned by the ODA, is integrated into the landscaping or infrastructure and is unassuming to say the least.

London Mayor Boris Johnson, CEO of ArcelorMittal Lakshmi Mittal, artist Anish Kapoor and engineer Cecil Balmond, pictured with model of the Orbit; photo James O Jenkins

London Mayor Boris Johnson, CEO of ArcelorMittal Lakshmi Mittal, artist Anish Kapoor and engineer Cecil Balmond, pictured with model of the Orbit; photo James O Jenkins

×And in Kapoor and Balmond they have a team that is likely to produce success. In London their most prominent collaboration was in Tate Modern's massive Turbine Hall. 'Marsyas' was a giant work, comprising of three steel rings joined by a single span of PVC membrane. Two were positioned vertically, at either end of the hall, while a third was suspended at the same height as the pedestrian bridge. Seemingly wedged into place, the relation between the three rigid steel structures created an interplay between vertical and horizontal.

The Orbit, in turn, creates new relationships with our traditional means of orientation. ArcelorMittal has gifted 1,400 tonnes of tubular steel to the Olympic project, and as one traces the profile of the tower-sculpture and notices how the square section rotates and changes in size along its journey, you realise that the marriage between material and artists and engineers is no accident. It winds and twists with its own logic, celebrating its own virtuosity in a way that is to some, unfortunately, profane.

Rendering of the Orbit, which is due to be completed in time for the 2012 Olympics in London

Mittal and Kapoor were both born in India, whilst Balmond was born in Sri Lanka; both former colonies of Britain. All of these men are now residents of London and are at the top of their respective fields. If the Empire produced its own statuary in which generals on horses were rendered in stone, then the Orbit, which proposes a multiplicity of views and interpretations, is a post-imperial monument. The Orbit’s apparently unstable form derives its strength from unexpected moments where its parts touch, a suitable monument to London, with its host of languages, cultures and ethnicities. It is an exciting and frequently unstable city of 7 million that is held together by a surprising, albeit grudging, tolerance. The way the project came about is hardly democratic, but at least the sculpture is a sincere gesture to the people of the city.

When one considers that a seriously considered alternative was to rebuild the Skylon, a monument to a festival that occurred some 60 years earlier, one does wonder whether the British would prefer to hold on to the symbols it understands rather than to be challenged by ones it does not yet comprehend.