Pop-up stars: temporary contemporary architecture

Scritto da Alyn Griffiths

London, Regno Unito

08.09.12

From huge temporary stadia to tiny transitory event spaces, pop-up architecture fulfils many roles and comes in many guises. In some cases the very latest technologies are used to engineer complex structures, while in others a readymade approach using scavenged materials is more appropriate. Architonic examines some key pop-up projects that are designed to make the most of their short lifespans.

The London 2012 Basketball Arena by Wilkinson Eyre Architects is one of the largest temporary venues ever built for an Olympic Games; photo © Edmund Sumner

The London 2012 Basketball Arena by Wilkinson Eyre Architects is one of the largest temporary venues ever built for an Olympic Games; photo © Edmund Sumner

×Of the nine venues erected on the site of this summer’s Olympic and Paralympic Games in London, three of them – the Basketball Arena, Water Polo Arena and Riverbank Arena – were designed to be completely dismantled following the competition’s conclusion, and their parts reused or recycled. The most architecturally ambitious and striking of these is the 12,000-capacity Basketball Arena, designed by British architects Wilkinson Eyre, which is one of the largest temporary venues ever constructed for an Olympic Games.

The undulating pattern on the façade results from the PVC skin being stretched over curved steel frames; photo © Wilkinson Eyre Architects

The undulating pattern on the façade results from the PVC skin being stretched over curved steel frames; photo © Wilkinson Eyre Architects

×The building’s 1,000-tonne steel portal frame provides a structural core with an enormous span that negates the need for internal columns or poured concrete foundations, meaning the building will leave a minimal impression on its site when disassembled. A PVC membrane stretched over three different arched steel modules covers the exterior, creating an undulating, textural surface. A blackout layer integrated into the ceiling enables moderation of light levels, while the walls are translucent, allowing daylight to permeate and the pattern of the external substructure to be illuminated from within after dark. The use of lightweight materials and an intelligently engineered frame enabled the skeleton and cladding to be assembled in a period of just six weeks and two-thirds of the materials will be salvaged and reused when the building is dismantled.

Carmody Groarke Architects repurposed the canopy and forecourt of a disused petrol station to create The Filling Station restaurant and arts space; photo © Luke Hayes

Carmody Groarke Architects repurposed the canopy and forecourt of a disused petrol station to create The Filling Station restaurant and arts space; photo © Luke Hayes

×Within an urban context, pop-up architecture can transform disused sites into venues for an alternative purpose and audience. An abandoned petrol station by the Regent’s Canal in London’s rapidly developing King’s Cross district provided such an opportunity for architects Carmody Groarke, who integrated the existing structures into their design for a multifunctional space containing a restaurant and arts venue.

The site has been allocated for housing as part of the area’s grand overhaul but, for the intervening two years, the developers chose to hand it over to pop-up restaurant veterans Pablo Flack and David Waddington, who previously worked with Carmody Groarke on Studio East, a temporary dining venue built from scaffolding and plastic sheeting overlooking the Olympic Park construction site.

The original forecourt can be used to host seminars and events, while the booth contains a 50-seat restaurant; photo © Luke Hayes

The original forecourt can be used to host seminars and events, while the booth contains a 50-seat restaurant; photo © Luke Hayes

×The Filling Station’s semi-permanent nature informed the choice of materials and building techniques used in its assemblage. Translucent fibreglass panels wrap around the existing infrastructure on the site, creating curves and angles that add interest to the exterior aspects, while shielding the space from the busy roads that flank the site on two sides. The petrol station’s original canopy and forecourt have been retained to create a sheltered space for events and talks, while the kiosk has been transformed into a dining room looking onto the canal. At the end of the Filling Station’s residency, the panels and the scaffolding skeleton holding them in place will be dismantled and reused elsewhere in the King’s Cross development.

The original forecourt can be used to host seminars and events, while the booth contains a 50-seat restaurant; photo © Luke Hayes

The original forecourt can be used to host seminars and events, while the booth contains a 50-seat restaurant; photo © Luke Hayes

×Another example of a semi-permanent structure squatting on a prime piece of urban real estate is Boxpark, a temporary shopping mall made from shipping containers that popped-up on an empty plot in the heart of London’s fashionable Shoreditch district in late 2011. The sixty containers that form the mall are arranged with forty at street level, most of which have entrances opening directly onto the pavement. The upper level hosts more shops, bars and cafés, with walkways and open areas for outdoor seating, all finished in raw materials that blend in with the area’s industrial aesthetic. The containers are surprisingly spacious inside and brands are encouraged to express themselves in the way they present their wares.

The panels are backlit at night; photo by Luke Hayes

The inherent mobility, stackability and robustness of shipping containers makes them a smart choice for pop-up construction. They have been used before as retail outlets or eateries, and they have been combined to create larger structures, such as fashion brand Freitag’s showroom in Zurich or Shigeru Ban’s multi-storey Nomadic Museum, but Boxpark’s owners claim this is the first time they have been used to build a mall offering diverse shopping and eating experiences. However, the exemplary aspect of the Boxpark concept is that it enables young companies who could never afford to open a permanent store in such a premium location to take on short-term leases, highlighting the commercial benefits of pop-ups in the retail sector.

Sixty shipping containers spread over two levels form the Boxpark shopping mall in London’s Shoreditch; photo © Ravi Sidhu

Sixty shipping containers spread over two levels form the Boxpark shopping mall in London’s Shoreditch; photo © Ravi Sidhu

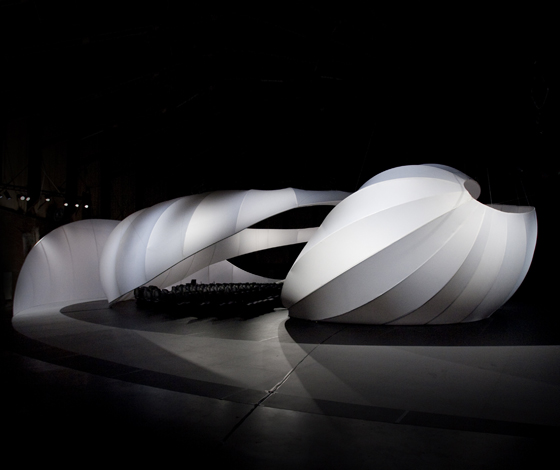

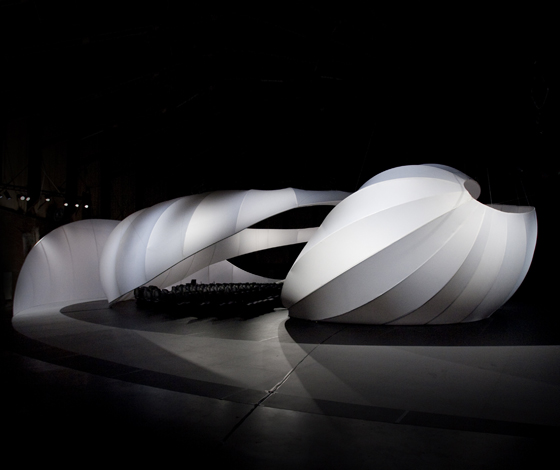

×Pop-up architecture also lends itself particularly well to temporary events and exhibitions and, in this scenario, often seeks to emulate the spectacular spatial effects achieved by theatrical set builders. When Zaha Hadid Architects was asked to design a temporary stage within an exhibition space at Manchester Art Gallery for recitals of Johann Sebastian Bach’s chamber music, the result resembled an intimate theatre set that enveloped the audience and performers in a continuous fabric ribbon.

The mall will remain at its current location for five years before being shipped somewhere else; photo by Alyn Griffiths

The mall will remain at its current location for five years before being shipped somewhere else; photo by Alyn Griffiths

×Expert acousticians recommended using a lightweight material that would not dampen the sound too much and the architects settled on a white synthetic fabric wrapped around a metal frame suspended from the ceiling. A stage, an auditorium and passageways were defined by a swirling form that contained the concert’s acoustics and created a voluminous and dynamic backdrop that punctuated the surrounding black space. The entire structure was designed to be straightforward to disassemble and reassemble elsewhere and has since appeared at the Holland Festival in Amsterdam.

Pop-up installations can be hi-tech and heavily engineered, but they can also be spontaneous and ramshackle. Dutch designers Rikkert Paauw and Jet van Zwieten create buildings from waste material and furniture scavenged from urban surroundings that are transferred into a refuse skip and transported to a suitable site where they are then used to erect temporary structures. Their enterprise, Foundation Projects, is so-named because the skips form the foundations for the buildings, whose shapes and properties vary depending on the environment from which the materials are gathered.

A ribbon of lightweight fabric swirls around the performers and audience in this temporary music hall by Zaha Hadid Architects; photo by Joel Chester Fildes

A ribbon of lightweight fabric swirls around the performers and audience in this temporary music hall by Zaha Hadid Architects; photo by Joel Chester Fildes

×Foundation Projects first appeared at Vienna Design Week in 2010 and subsequently at the Milan Public Design Festival in 2011 before Paauw and van Zwieten brought it to their home town of Utrecht in 2012, where three separate small buildings were assembled in different districts before being moved to a central location to form the hub of a mini festival. Activities and a bar were hosted within the structures and images and videos recorded during the streetcombing process were projected onto their various surfaces.

Foundation Projects by Rikkert Paauw and Jet van Zwieten uses waste materials to create small buildings; photo by Hein Lagerweij

Foundation Projects by Rikkert Paauw and Jet van Zwieten uses waste materials to create small buildings; photo by Hein Lagerweij

×For six weeks in the summer of 2011, an ugly and unused plot beneath a motorway flyover close to the Olympic Park in east London became home to a temporary cinema and events space built by architecture and design collective, Assemble. The previous year the group, which was initiated by several Cambridge architecture graduates and some of their friends, had transformed a disused petrol station in London’s Clerkenwell into a pop-up cinema by suspending a wrinkled silver curtain from the canopy covering the forecourt. With Folly for a Flyover, the expanding collective took on a project with a greater scale and budget and were able to draw on a larger network of volunteers attracted by the popularity of their previous projects.

Beneath the massive concrete beams of the flyover a simple bank of seating descended towards the canal that runs along one edge of the site. A core of scaffolding supported the stalls and the adjacent structure, which mimicked the brick buildings of the local borough but was merely a cosmetic frontage for the café and events spaces. Construction was completed in a month by a team of volunteers using locally sourced materials, including wood and clay bricks, that were removed and reused locally once the folly’s brief occupation had ended.

Folly for a Flyover was built by architecture collective Assemblage under a motorway in east London; photo by David Vintiner

Folly for a Flyover was built by architecture collective Assemblage under a motorway in east London; photo by David Vintiner

×The buildings created by Assemble and Foundation Projects exemplify pop-up architecture in its rawest form, emerging directly from the immediate environment and performing a specific function before disappearing again without a trace. No matter where they are and what they are made from, the point of successful pop-ups is to make the most of the space, time and materials that are available and to create experiences that are definitively contemporary.

Terraced seating under the flyover created a covered cinema; photo courtesy Assemble