Maine Journal

Scritto da David Sokol

Washington, DC, Stati Uniti d'America

11.02.09

No design tour of Maine is complete without a stop in Portland. This tiny city is the largest in the state. Somehow, that’s emblematic: Despite all its efforts to be cosmopolitan, muscular coastline and forests are always nearby.

No design tour of Maine is complete without a stop in Portland. This tiny city is the largest in the state. Somehow, that’s emblematic: Despite all its efforts to be cosmopolitan, muscular coastline and forests are always nearby.

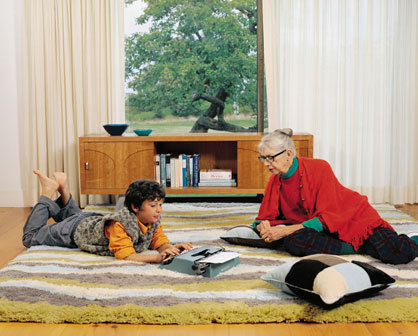

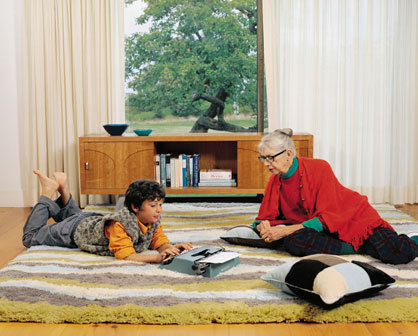

Angela Adams and Sherwood Hamill are Portland’s reigning pair of designers. Although Hamill’s modern furniture studio had operated previously, in 1998 the husband and wife teamed up, with his business operating alongside and complementing her newly launched eponymous brand. Hamill’s mid-century-inspired, occasionally anthropomorphic furniture pieces haven’t necessarily yielded the media attention they deserve, but Adams’s work slowly, and then not-so, infiltrated the popular design language. The telltale rugs that inaugurated Angela Adams has won devotees, so much so that the company now operates a collection of haute, custom pieces that will introduce new designs this autumn. The oeuvre also includes Ann Sacks tile patterns and contract-grade flooring and upholstery for Shaw and Architex, while shoppers on the other end of the price spectrum may appreciate Adams’s patterns on handbags that now feature sustainable fabrics.

About those patterns. Adams was born and raised on an island off the Maine coast, mostly isolated from time and human imprint. The appeal of Adams’s work is grounded in that upbringing. Translated into rugs, seascapes and landscape elements—say, a field of pebbles—comes alive with color and texture. Sometimes, as for Ann Sacks, those references are abstracted to the point of no recognition: Executed with soft curves and in earthen colors, patterns seem conversant with the same period that informs Hamill’s work. I sat down with both designers to discuss the aesthetic links between them, manufacturing locally, and the timidity of the American consumer.

Why did you explore hand-tufted rugs once you decided to move beyond decorative painting?

Angela Adams: I loved doodling and had always doodled, and I really wanted to find an application for these sketches. But I didn’t want to design for one product, I wanted to design a business that could warrant a lot of different products. That leap had to start somewhere, so it started with custom rugs. And Maine has a long history of rug-making.

Was the production local, then?

AA: Yes. Sherwood was manufacturing locally. I’m not a craftsperson like Sherwood is, so I had to find mediums for my designs. I found a local rug production studio and they made the first few. Then, for many years, the first floor of our building was devoted to rug- and furniture-making. Sherwood’s expertise in design, manufacturing and craft combined with mine in sketching and having a vision for a multifaceted business.

Could you say that you’ve helped sustain dying craft industries in Maine?

Sherwood Hamill: I don’t think they’d be unemployed. I think people who really want to make their art are going to find a way.

AA: There was this idea that we could get the shoemakers whose factories had closed to make our handbags and things. On the other hand, customers don’t want to pay for handmade-in-Maine bags. It’s a ping-pong conversation. First they were upset because we had overseas manufacturing, and then they didn’t want to pay for locally made products.

So you are seeking local manufacturing nowadays.

AA: We definitely have a focus on producing as much locally as we can. When we design a product we examine our local resources and look outward from there, from Maine to New England to nationwide. Our furniture and a lot of the accessories in our Portland store are made in Maine. We get much better quality, and certainly better control when we’re making it here: There’s an advantage to it not going through so many manufacturers and managers. There are challenges to manufacturing in the U.S. because the U.S. manufacturers aren’t always so flexible. But those that are determined to stick around are getting more flexible.

Let’s move on to the vocabulary of these products. Angela, I would say your work is somehow informed by your childhood growing up on a remote island off the coast of Maine, seemingly frozen in time.

AA: One thing I hope people understand is you don’t have to be from an island to understand it. People do say there’s a mid-century influence: I know there have been designs reminiscent of my grandmother’s linoleum floor, and that environment was comforting to me. We’re inspired by our grandparents’ generation—the old-time craftspeople who had garage workshops. It’s really that kind of lifestyle we’re inspired by, although I think there is something there that seems to be getting lost now. And living in Maine we have seasons, the tides, and wonderful colors for inspiration.

As for the pieces that refer directly to nature, how do you decide when to embrace the abstract versus the figurative?

SH: Could you let me answer for you?

AA: I’d love that.

SH: My take on how Angela operates is that the inspiration is the decision maker.

AA: And can I answer for you?

SH: Sure, that would be great.

AA: Sherwood’s design process is really unique, and hasn’t been articulated very much. Knowing Sherwood as well as I do, I can say his furniture looks like him. When somebody’s design has the total spirit of who he is—that’s a serious amount of soul. You can tell by sitting here, one of us is a lot more animated and colorful and the other is more minimal and modern and subtle.

Angela’s animated patterns and scenes and Sherwood’s modern and subtle furniture dovetail perfectly. Does one person’s perspective influence the other?

SH: I recall first noticing how our work really does look well together. And that was at the Chicago Design Show in 1998. Angela’s company was just starting, and at these trade shows we put the rugs and furniture together and they just seemed to work.

AA: We both were committed to being designers, but we didn’t want to build two businesses side by side. We realized that when you put the furniture and rugs together, that created a comprehensive, comforting environment. We were really inspired by that. I definitely think the pieces complement one another, in the same way that we do in business.

One can find Angela Adams in both the residential and contract markets. Are there different criteria for these channels?

AA: I think we do our best work when we’re able to sit down, get a clear understanding of the use and the customer, and then apply our language to that. I think it can slow down the process a lot of times when there are too many cooks in the kitchen. In all of our licensing arrangements, we have approval of every part of the process.

One thing that is exciting for us, and certainly timely, is that healthcare is becoming more hospitality-focused, and hospitality is becoming more residential. Which is very much in sync with what we do anyway - we don’t reinvent ourselves for an industry. Our goal is to make environments that are inspiring and comforting.

What process of research and experimentation do you undertake when moving into a new design discipline?

SH: Angela’s patterns are so applicable to so many different products, it’s just a matter of adapting the scale and color to the different channels we talked about. I think the biggest design challenge is really a marketing challenge: making sure the consumer is going to accept the product, especially considering the homogenization of design taking place with the bigger retailers.

AA: We love the big retailers. The balance between aspirational design and accessible design is something we pay close attention to. And it’s those major retailers that have allowed us to have more accessible products out there. In places our friends and family can shop.

Considering how the brand tries to reach out to all consumers, would you also say there’s an American quality to the brand?

AA: It doesn’t seem that Americans have a lot of confidence in curating their own homes or lives. There seems to be a mindset that every season has its rules for what you’re supposed to look like and live like. People feel like they have to buy the components. What we’re trying to do is to pare down nature to a comforting language that people can really relate to and that is timeless

SH: There’s also a distribution problem. There’s so much talent here, but there are not many alternatives to get good ideas to the marketplace. And when designing for large retailers, the buyer has a tremendous amount of power over what is on those shelves.

AA: Sherwood said something a second ago that’s really important about marketing. It’s not just selling something, it’s about educating the consumer about what that something is. We all know plenty of designers or artists that put out beautiful product but don’t sell it. We take that really seriously. So when we design a product, it doesn’t do any good if we’re not able to articulate the inspiration or the use so that the consumer can understand the difference between it and the product next to it. The tapestry Boo Boo’s Dream, for example, was inspired by the idea of collecting for generations: I thought it was something Doris Duke would have collected in Shanghai. Simply, part of our design process is articulating the intent.

Maine Blueberry Ginger Jam and Strawberry Rhubarb Jam

So, rather than call your work ‘American,’ maybe we say that it is reconciling the country’s rugged individualism of the past with the mindlessly consumerist culture of the present.

AA: That’s an interesting way to look at it. I think maybe we got disconnected by losing our neighborhoods, too. We’re inspired by the lifestyle of getting off the school bus and hanging out with the old lady across the street, or riding around the island or the town with the guy who drives the oil truck. We’re losing that, and it seems like there is an insecurity or discomfort among Americans because of it.

SH: I agree. Maybe a symptom of that is consumers’ not wanting to take risk with design, but rather feeling safe in those things and ways that aren’t new. Although, when you think about tradition, it is rooted in other places. So what is uniquely American is a good question.