Architecture Iran

Scritto da Dominic Lutyens

London, Regno Unito

26.01.16

With Iran coming in from the cold, as it were, the heat is definitely on in terms of its architectural scene. Then again, many argue that the straitened era of sanctions has itself provided fertile creative ground for young Iranian architects.

The decorative, polychrome exterior of industrial glass company Kaveh’s Tehran office, which was completed in 2015, also broadcasts what the firm manufactures

The decorative, polychrome exterior of industrial glass company Kaveh’s Tehran office, which was completed in 2015, also broadcasts what the firm manufactures

×On January 16, ‘Implementation Day’ — when the International Atomic Energy Agency verified that Iran had met all commitments under last summer’s nuclear accord to restrain its nuclear programme — was finally announced. It signalled the end of 10 years of economically crippling nuclear-related sanctions, and Iran’s chance to reconnect with the global economy. It’s in a strong position to do so: it’s the second largest economy in the Middle East after Saudi Arabia, and has the world’s largest reserves of natural gas and the fourth largest of oil. And, despite the international isolation imposed on it by sanctions, Iran is absolutely no cultural backwater: half the population own smartphones and are members of social networking sites.

The premise of A Beveled Building, say architects Ayeneh Office, who redesigned it, was to hide unprepossessing views of a telegraph pole and ugly building opposite. Angled windows direct views away from these eyesores

The premise of A Beveled Building, say architects Ayeneh Office, who redesigned it, was to hide unprepossessing views of a telegraph pole and ugly building opposite. Angled windows direct views away from these eyesores

×Additionally, new legislation has been introduced to attract more foreign investment, making it possible, for example, to register an Iranian company with 100 per cent foreign capital. Two previously depressed sectors that look set to benefit from this are Iran’s construction business and housing market. Yet before sanctions were lifted, architecture in Iran was thriving, and today, some even feel that the country’s relative cultural isolation caused it to blossom, and that a rapprochement with its former

enemies — and inevitable merging with the globalised world — will undermine this.

The uninspiring semi-triangular plot of the Niayesh Office Building inspired its architects to create a visually arresting exterior with intriguing variations in the heights of its floors and dimensions of its windows

The uninspiring semi-triangular plot of the Niayesh Office Building inspired its architects to create a visually arresting exterior with intriguing variations in the heights of its floors and dimensions of its windows

בIn recent years, sanctions kept foreign architects and mainly starchitects out of Iran, which was a blessing,’ says architect Amir Sanei of London-based practice Sanei Hopkins, who was born and raised in Iran and qualified in the UK. ‘This allowed young Iranian architects to flourish and develop distinctive languages within the same sanction-enforced constraints of available technologies and materials.’

The strong horizontal lines of the office building’s facade are echoed in its interior, with its long, narrow, dramatically angular recesses in the ceiling, which incorporate lighting

The strong horizontal lines of the office building’s facade are echoed in its interior, with its long, narrow, dramatically angular recesses in the ceiling, which incorporate lighting

×Looking now at a sample of contemporary Iranian projects reveals that the country’s architects are typically preoccupied with geometry, light, colour and context. Take A Beveled Building in the city of Najafabad, central Iran, an existing building cleverly redesigned by Ayeneh Office, whose main, thoroughly pragmatic aim was to conceal the views it had hitherto been stuck with, namely of an unsightly telegraph pole and building opposite. The redesigned building’s relationship with its environment has been cleverly transformed by giving it a beveled façade featuring projecting, angled windows that hide the pole and building, diverting the eye instead to vistas of a luxuriantly green tree and mountains. The architects also opted for a uniformly white façade that capitalises on the play of shadow and light on it and unifies its surface, otherwise broken up by its many jutting, irregularly sized windows.

Hooba Design Group, the architects of the Valiahdi Commercial Complex in Karaj, use the term ‘multidimensionality’ to describe its complex, rhythmically patterned facade; photos Parham Taghioff (top) and Abbas Havashemi (above)

Hooba Design Group, the architects of the Valiahdi Commercial Complex in Karaj, use the term ‘multidimensionality’ to describe its complex, rhythmically patterned facade; photos Parham Taghioff (top) and Abbas Havashemi (above)

×Meanwhile, Behzad Atabaki’s new, six-storey Niayesh Office Building in Tehran has been influenced by the architects’ feeling that its semi-triangular site was uninspiring and needed enlivening. Wishing to avoid visually monotonous forms, the architects came up with a structure comprising storeys that appear to vary in terms of height as well as an eccentric combination of narrow windows that look stretched, paired with more conventionally rectangular ones. Nevertheless, the architects unified this fragmented-looking exterior by cladding it with one material — stone. While idiosyncratic, the façade’s strong horizontal lines, flat roof and curved corners also look familiar, recalling as they do both International Style and Art Deco architecture.

The dynamic patterns of the Valiahdi building’s exterior invade its interior, thanks to stained-glass windows, which project coloured patterns indoors when sunlight hits them; photos Pooyeh Nouryan (top) and Parham Taghioff (above)

The dynamic patterns of the Valiahdi building’s exterior invade its interior, thanks to stained-glass windows, which project coloured patterns indoors when sunlight hits them; photos Pooyeh Nouryan (top) and Parham Taghioff (above)

×Context has also strongly influenced the structure of the Valiahdi office block in the city of Karaj, 20 kilometres west of Tehran: the grid of windows on its undulating exterior was inspired by the surrounding urban street layout. And, viewed in conjunction with the Niayesh and A Beveled Building projects, it suggests the existence of a peculiarly Iranian trend for facades featuring complex, geometrical, 3D compositions. According to Sanei, this is not a new phenomenon: ‘The architecture of the Persian empires of the past 2,500 years was preoccupied with geometry, light and space.’ In fact, another key characteristic of the Valiahdi office is its use of light combined with colour. Its windows are inspired by the ancient Persian tradition of orosi (stained-glass) windows, magnificently vibrant examples of which can be seen in Tehran’s Golestan Palace. The colours of the office’s windows — brick and turquoise, which were commonly used in traditional Persian architecture — deliberately invoke Iran’s past. The stained glass also serves a practical purpose, helping to deflect heat from strong sunlight flooding into the building.

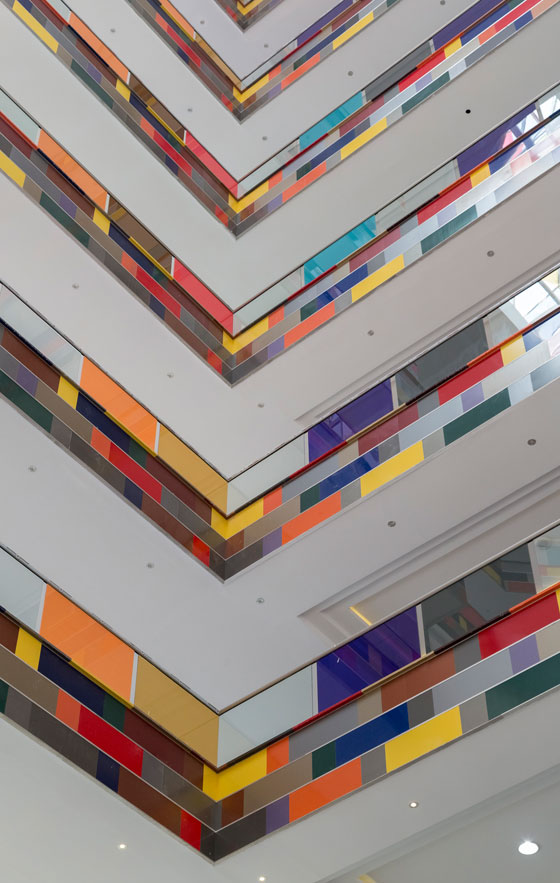

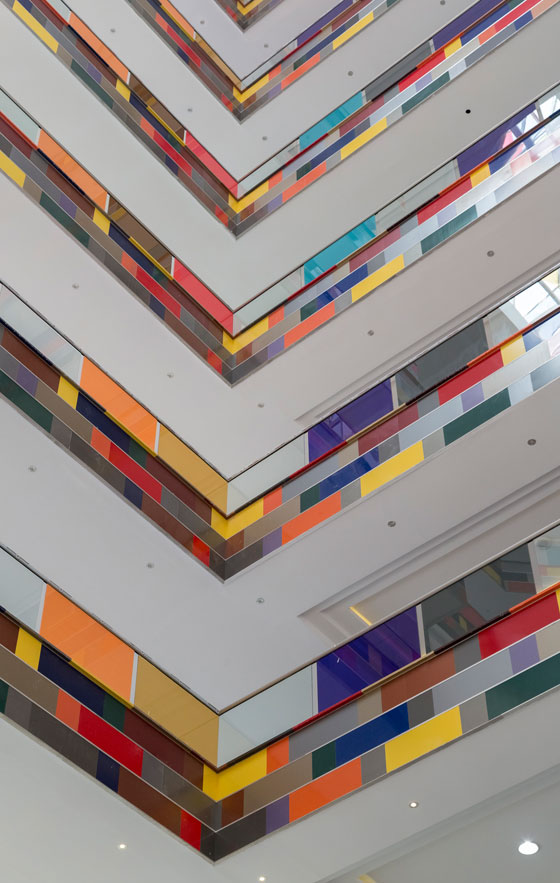

The site of glass company Kaveh’s office building forced its architects to give it a rectangular structure. To avoid this looking ‘monotonous’, they dreamt up a visually spectacular, multicoloured glass facade. Its atrium is similarly rainbow-hued

The site of glass company Kaveh’s office building forced its architects to give it a rectangular structure. To avoid this looking ‘monotonous’, they dreamt up a visually spectacular, multicoloured glass facade. Its atrium is similarly rainbow-hued

×Light and colour have been used more extravagantly still in the Tehran office building of industrial glass company Kaveh, designed by Amirabbas Aboutalebi of AA Design. Once again, the site largely determined its long, rectangular shape, although its polychrome façade — reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s L’Unité d’Habitation apartment block in Marseille — is anything but predictable, while its internal atrium is strikingly striated with bands of jewel-bright glass. An interest in sustainability and psychological wellbeing are other aspects of this project: the abundance of daylight inside it is designed to reduce the need for electric lighting and so save energy, the profusion of colour in the windows is intended to induce wellbeing in its 4,000 employees, while the atrium retains heat during the winter and expels stale, warm air in summer.

Contemporary Iranian architecture references ancient architectural traditions but does so playfully and with verve. It remains to be seen how it evolves — and whether it retains its integrity — when it fully re-enters the global arena.

The singing colours of the Kaveh building’s atrium are practical as well as decorative – they also draw light into the building. Concentrically arranged octagons at different ceiling heights provide another decorative element

The singing colours of the Kaveh building’s atrium are practical as well as decorative – they also draw light into the building. Concentrically arranged octagons at different ceiling heights provide another decorative element

×