No more static: THE MOVING ARCHITECTURE OF KWK PROMES

Scritto da Jaime Heather Schwartz

Berlin, Germania

29.05.19

The work of Polish office KWK Promes is on the move thanks to its super-kinetic architectural elements.

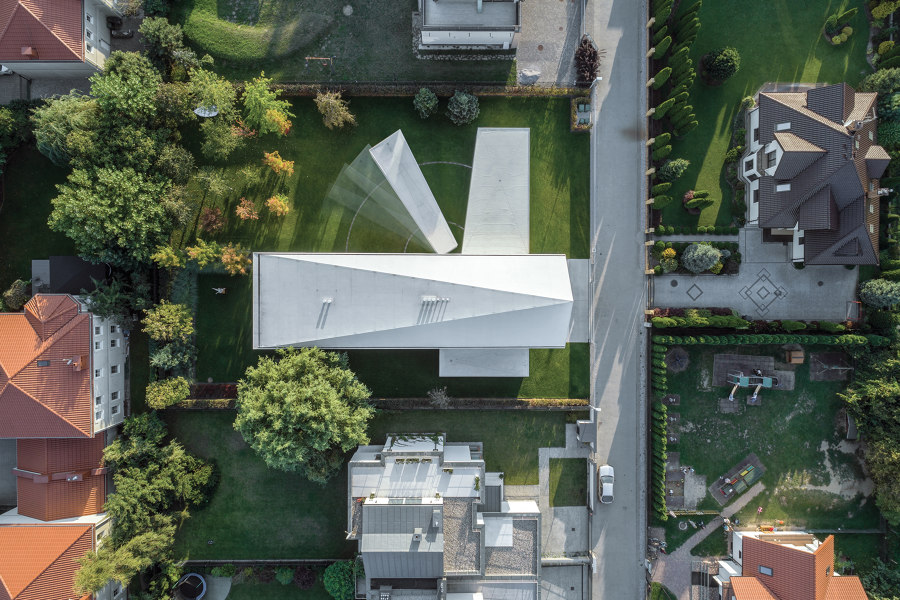

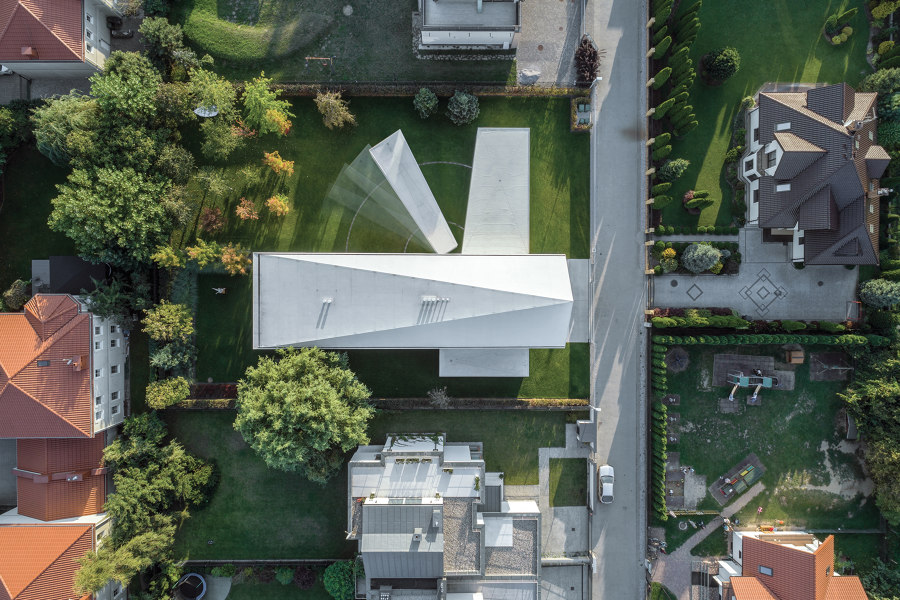

Quadrant House 2018, Katowice, Poland Photo: Jaroslaw Syrek

Over the past ten years, designs with moving elements have become a signature of Polish architect Robert Konieczny, founder and director of Katowice-based practice KWK Promes, one of the country’s most internationally renowned architecture firms.

Never just a gimmick, his “moving architecture” is always employed as a means to an end, providing creative, adaptable building construction solutions. Beyond their purely utilitarian function, these mobile mechanisms offer a way for buildings to both dramatically transform and to seamlessly integrate into their surroundings, resulting in a profound dialogue between structure and site.

Architionic spoke with Robert Konieczny about his practice and some of his projects.

You've mentioned the Safe House (2009) as being the starting point for your current practice. In the last ten years have there been significant technological developments that have facilitated the evolution of your moving architecture projects?

The Safe House has started a path of moving projects in which we’ve developed the idea of buildings that are more open to their surroundings while maintaining absolutely clean forms. We started to look for technological solutions to questions: how to build sliding walls about twenty metres long or make a high and wide roller blind for the whole house? We had to develop our own prototypes and also established a partnership with a company that works for the aviation industry in addition to NATO and even NASA. I will only mention the Plato Gallery in Ostrava, which will be an innovative exhibition space interacting with the city through the opening of walls.

But I'm not inspired by technology and I don't follow its development very carefully, because then I would focus on solutions that are only available on the market. It would be limiting and my task is to invent new things, sometimes not even knowing if I will find the right technology for them. However, based on experience and intuition I choose solutions that are usually realistic to build and sometimes, this is how prototypes change over time into systemic solutions.

You describe "moving architecture" as having the power to change a structure's expression and adapt it to changing conditions. In the Quadrant House, this plays out literally with a wing pivoting in response to the movement of the sun. What are your thoughts on how moving architecture affects the people who inhabit or experience your designs?

In a normal static building, the architect sets the final form and mode of operation - the user has to adapt, and any changes require redevelopment and are difficult to make and costly. In a building with moving elements, the user has more possibilities – he can change and thus adapt the space to his expectations or to the specific environmental conditions at the time. It is the inhabitant who, by controlling the walls in the Safe House, changes the shape of the building and its surroundings.

In moving architecture, the focus is shifting from architect to inhabitant. The user becomes more important because it is the user who decides on the performance of the building at a given moment. The building itself can react better to the changeability of life, seasons or day cycle.

Quadrant House Photos: Juliusz Sokolowski (1,3), Olo Studio (2)

Your designs – for example, Konieczny’s Ark, By the Way House and even your recent Unikato development – display a consideration for their surroundings, while simultaneously delivering a visual impact. How do you keep these two drives in tension?

I always aspire to find one pure idea, which is the answer to all the problems, issues and challenges of the project. It seems simple, but it is extremely difficult. But when something like this comes up, the project starts to work itself out. Of course, the final effect is supported by a very long way of chiselling the project, eliminating unnecessary things, fighting many battles at every stage, including construction.

By the Way House (top); Unikato (above) Photos: Jaroslaw Syrek

At a recent accompanying talk to your exhibition at the Architecture Gallery Berlin, you said you're engaged in "creating global architecture with Polish traditions". Can you say more about this?

That's what Philip Jodidio said. He meant that in projects we are inspired by our backyard, and we are getting buildings out of it, which resonate more widely outside Poland – to the whole world.

I never wanted to imitate what others do, but to do my own thing. I even coined a slogan for myself that I would like to compete with the whole world, even if the world does not know about it. I knew I could only win with the quality of my ideas. Because if you are based on a concept, you are not a slave to fashions, local patterns or your formal habits. Often the idea leads to a surprising and fresh effect.

Konieczny's Ark Photos: Olo Studio (1), Jakub Certowicz (2)

What would be your dream project?

I used to dream about doing something sensational in a very famous place. But when we built the small Dialogue Center "Przełomy" Museum in Szczecin, shortly after its completion, it won the titles of Best Public Space in Europe and the World Building of the Year at the World Architecture Festival in Berlin. That's when I realised that when you make a good building, it makes the place famous.

But invariably my dream is to create projects in which you come up with not only a strong idea but also a universal one, which other architects can later use and develop. An example is our Living-Garden House or Autofamily House.

Dialogue Center "Przełomy" Museum Photos: Juliusz Sokolowski

© Architonic