Nothing to fear for an engineer

Scritto da Klaus Leuschel

Bern, Svizzera

13.09.16

Those looking for great and inspiring engineering solutions need to have an almost naive belief that anything is possible.

We have to thank the Italian architect Adolfo Natalini for the lamentable insight that when 100 children enter the school system all 100 of them draw and paint with enthusiasm, whereas when they leave school perhaps only one of them is able to draw or paint at all. We could probably come to the same sad conclusion in terms of handicraft work, especially as children – both boys and girls – stopped playing with modelling kits which stimulate creativity and the imagination a long time ago and now prefer to make copies of the spaceship from the 'Star Trek' movies in the way that is specified for them by a Danish toy company.

It is accordingly all the more surprising that in his "Inside Out" exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2013 London architect Richard Rogers made a point of providing a model of London for the benefit of kids in one room of the exhibition, together with the possibility of making playful additions in the form of imaginary buildings.

In the process it was not the past but rather our future which was important to Rogers, who attributes his enduring enthusiasm for the constructional possibilities of architecture in part to his experiences with long-forgotten Meccano (or Stabilo) sets during his own childhood.

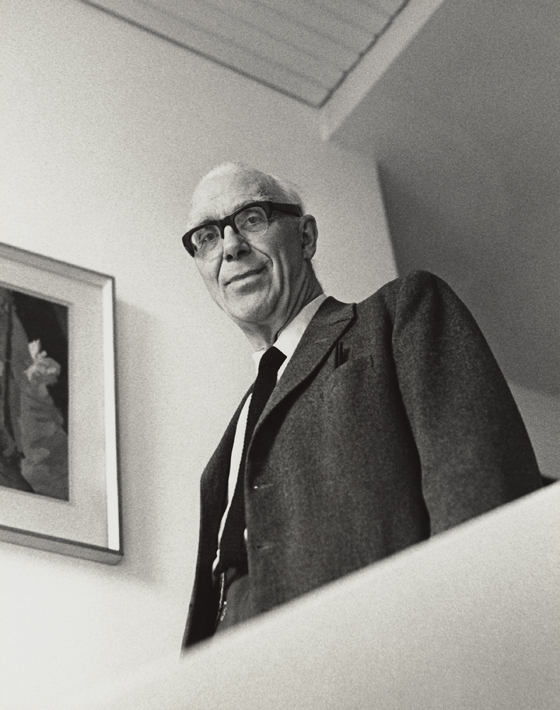

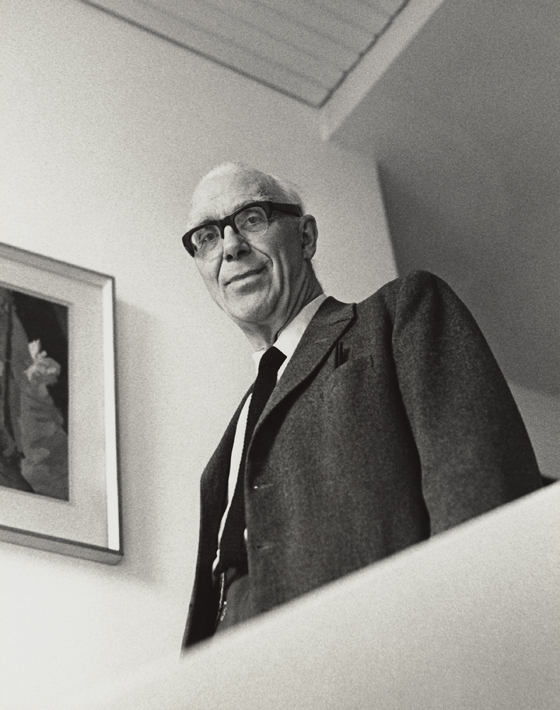

Sir Ove Arup by Godfrey Argent, 25 April 1969; © National Portrait Gallery, London

Those who are looking for major and in the extreme case inspired engineering solutions need to retain an almost naive fascination for what is probably expressed in the most concentrated form in the advertising slogan 'Nothing is impossible'. In architectural history the Sydney Opera House designed by the Danish architect Jørn Utzon has long been put forward as a spectacular example of a project which could only be rescued by a firm of engineers.

And this wasn't just any old firm of engineers, but that of Denmark's Ove Arup (1895 – 1988), who initially studied philosophy before a course in mathematics took him into engineering. This career contributes significantly to explaining how in the twentieth century this Londoner by choice became one of the major figures in the history of his field.

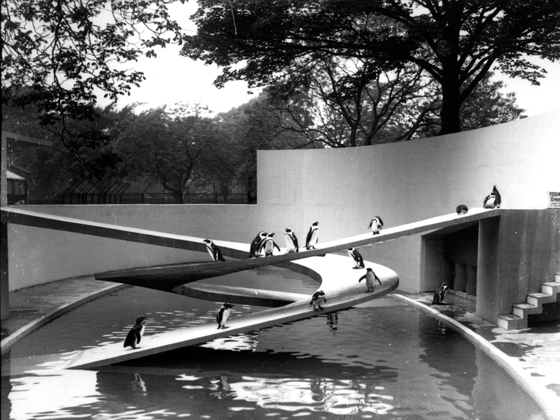

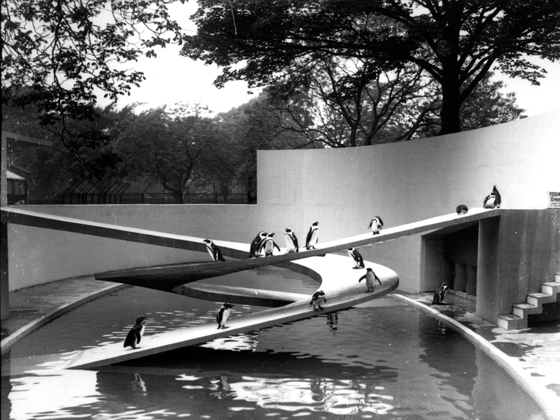

At beginning of the thirties the architect Berthold Lubetkin (Tecton Group), himself an immigrant who had had to flee Stalinist Russia as a representative of the avant-garde, joined Ove Arup in creating the Penguin Pool project at London Zoo. It goes without saying that this masterpiece of modern architecture has long been subjected to the ridicule which has become acceptable in the recent past. It was claimed that there was no way penguins could feel at home on the cantilever-mounted concrete spiral, forgetting that over a period of 75 years no problems have ever been reported, either by the zookeepers, the management of the zoo or animal welfare activists - at least not with regard to the penguins.

Sydney Opera House under construction; 6 April 1966; © Robert Baudin for Hornibrook Ltd. Courtesy Australian Air Photos

Sydney Opera House under construction; 6 April 1966; © Robert Baudin for Hornibrook Ltd. Courtesy Australian Air Photos

×It was at the latest his brilliantly simple solution for the Opera House in Sydney on which Ove Arup's reputation as a problem solver is based. In London Utzon's idea was transferred to a spherical model from which the 'shell' segments of the roof were cut – like pieces of cake – and transformed into prefabricated elements. Accordingly Arup, who had immediately recognised the significance of the roof and robustly defended it against those who made the decisions on the project, was transformed into its rescuer.

Ove Arup's reputation is based on this and similarly groundbreaking achievements as a structural engineer. The Dane was valued highly by Le Corbusier, who even painted his portrait, and Walter Gropius saw in him a kindred spirit who represented even more rigidly than Gropius himself the position that architecture can only lead to the best possible result if architects and engineers work together from the very beginning as equals and with a solutions-oriented approach. 'Quality' was one of his central commitments, and he regarded 'money' as simply the necessary resource for the fulfilment of major ambitions.

The team in Sydney also included a young Irishman who had been sent to Australia because of his talent. His name was Peter Rice. Because of his part in the work on Centre Beaubourg (once more as a member of Arup's team) the "James Joyce of the engineering profession" (Jonathan Glancey) advanced to become a partner for some time to Renzo Piano (The Menil Collection; consultant engineers: Arup).

Apropos Beaubourg (architects: Piano + Rogers), with its six unsupported levels – each covering an area of 7'400 m2 (for purpose of comparison, a football pitch has an area of approx. 7’140 m2) – this project is regarded as a further milestone in engineering. The head office of HSBC in Hong Kong (Foster + Partners), Kansai airport in Japan (Renzo Piano Building Workshop), the Bird’s Nest in China (Herzog & DeMeuron): the list of Arup's reference projects is as geographically extensive as it is resonant.

At present Arup has a global workforce of 14,000. Other successful engineering firms such as Happold in Bath or that of Cecil Balmond in London probably would not exist without the experience of their owners with Sir Ove. The tall music lover never had any hesitation about employing unconventional solutions, as long as they served their purpose. Accordingly for a time Peter Rice had a company of his own in Paris, which placed him in direct competition with Arup, while at the same time he acted as a partner on a part-time basis with a seat on the company's supervisory board.

Exterior view of Centre Pompidou; © Ian Dagnall Alamy Stock Photo

This partnership is one of the special features of a company which is actually owned by a trust. To the present day what makes this structure individual is that shares are allocated to employees, which enables them to join the management team as partners. These shares can only be sold back to the trust (e.g. in the event of retirement or death) at a specified value. True to the principle of its founder that money can only be the means to an end, the company therefore does not really belong to anyone.

How strong the influence of the Dane remains even after his death is made clear by the way his staff adopted his principle of 'total design', and perhaps even more the spirit of innovation shown by the company. However, in the recent past this innovative spirit seems to have declined a little. Against the background of epoch-making architectural masterpieces covering more than half a century, a facade entitled "SolarLeaf" with a solar thermal effect (Arup/Colt/SCC©) seems to be a little insubstantial. Perhaps it is only the manifestation of a change which not even architecture can avoid: away from star thinking and a move towards teamwork and new technological approaches.

In other respects the name of this firm of engineers has never been discredited to the present day, as is shown by this example: during work on the Opera House in Sydney, in 1957 Arup rented the Pegasus MK I Computer of Ferranti Ltd., the first of its kind in the UK, on an hourly basis for the complex calculations. The reason: time was money! When the roof was completed in 1962, the follow-up calculations indicated that the traditional manual approach – at that time still using the slide rule – would have added a further five years to the completion of the building.

© Klaus Leuschel for Architonic