Never Built New York

Scritto da TLmag

Brussels, Belgio

16.08.17

It's called the 'City of Dreams' and yet, some of New York City's most radical, technologically advanced buildings were never realised. Their combined histories expose challenges the famous metropolis must confront as well as fundamental problems lying at the crux of urban design.

In the summer of 1833, painter Thomas Cole sent Luman Reed, one of New York’s wealthiest merchants, a detailed prospectus for a series of canvases he wanted to display in Reed’s no. 13 Greenwich Street mansion. Cole told his patron that the paintings would chart man’s “progress from Barbarism to Civilization, to Luxury . . . to the state of Ruin & Desolation.” The artist struggled for some time before he devised a suitable title, hitting upon The Course of Empire.

The oils, which proved to be a hit, were more than an allegory of a great nation’s or city-state’s rise and fall. In a sense, Cole inaugurated the essential idea of New York City: He self-consciously aligned the fate of his adopted city with that of the Roman Empire.

What lay very much on the surface of Cole’s paintings was a teeming mercantile city always edging the brink of collapse. The engine of New York’s economic prowess, he suggested, would invariably outrun the brake of its cultural and social compact. Between these two poles, of unrestrained growth and the need to bring that growth to heel, is the stuff of Never Built New York. Cole’s neo-classical archetype, so strenuously imposed, in a way predicts generations of efforts to find one that would suitably confine the city, that would reform its tendency to be messy, raucous, and, to borrow one of Rem Koolhaas’s famous descriptions, “delirious.” Someone always wanted the place to be ship-shape.

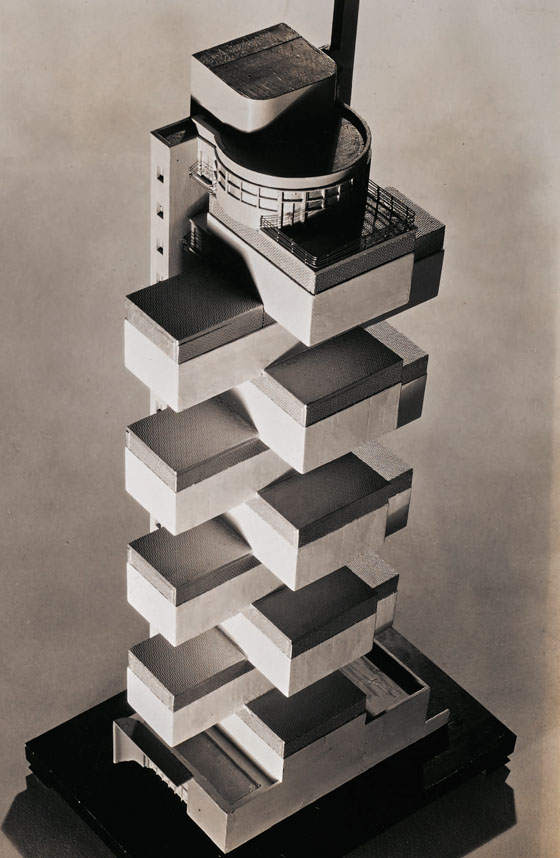

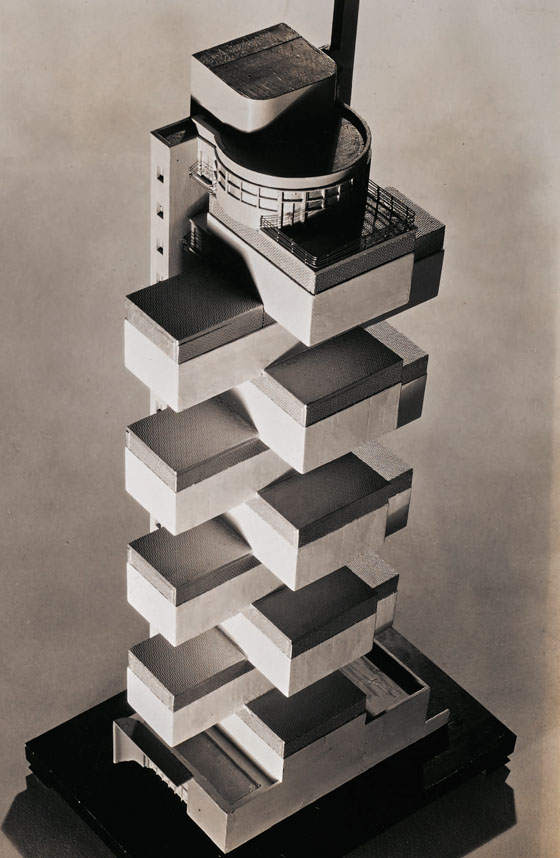

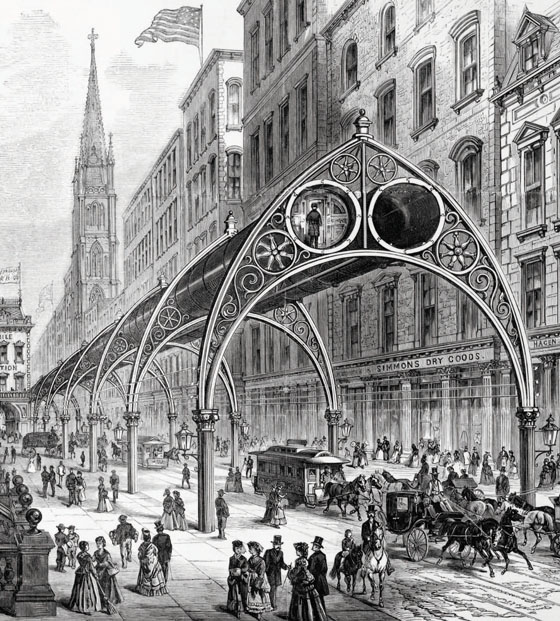

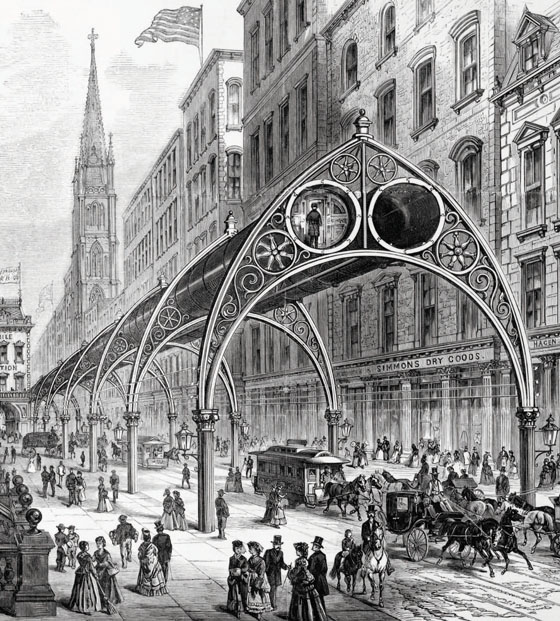

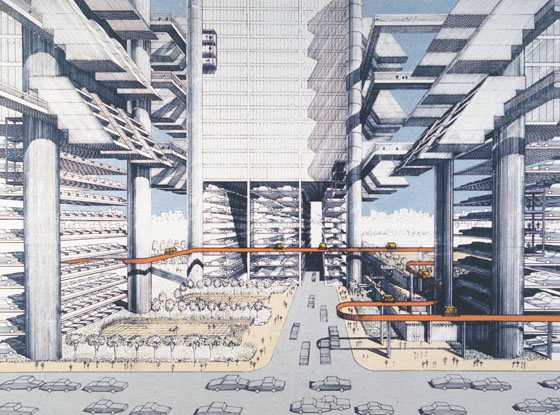

Rufus Gilbert, Gilbert's Pneumatic Railway (top). Mckim, Mead and White: Grand Central Terminal, 1903 (middle). Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan Expressway (bottom)

Rufus Gilbert, Gilbert's Pneumatic Railway (top). Mckim, Mead and White: Grand Central Terminal, 1903 (middle). Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan Expressway (bottom)

×Never Built New York represents, in one respect, 200 years of failed attempts to confer that order, rationality, efficiency, or “beauty.” Early on, the way to do so was to root around in Europe, ancient and contemporary, and find an example: Haussmann’s Paris with its grand boulevards, Tuscany with its hilltop towers, Periclean Athens with its ordered architecture. Need a new museum? Consult the drawings of the Louvre. Want a monument? Borrow from the Egyptians. Later, the strict language of modernism, wiping away the detritus of history and the complications of street life, offered a similar panacea. Victor Gruen’s domino-like line of slab residential towers stacked like dominoes along Roosevelt Island (then called Welfare Island), looked impressive, futuristic, even light-weight from afar. Under a raised plinth would lay staples of the imagined time: carveyors and moving walkways. But from up close the idea could easily have been built in the Communist Eastern bloc, a terrifying monument to over-scaled ego and urban condescension. Today, in much the same vein, sterilized—and seemingly serialized—supertall towers with vaguely European names compete with cleaned up remnants of a messier past, from the High Line to the glorified shopping mall that is SoHo.

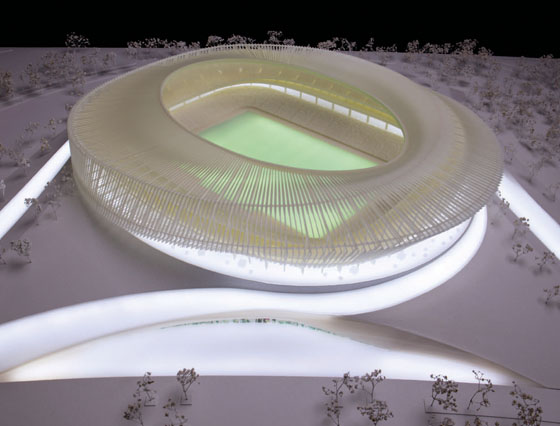

The other pole, the desire to break free and to make the city in a different image, has yielded breathtaking, but no more successful, forays: Alfred Ely Beach’s Pneumatic Rail, Gustav Lindenthal’s North River Bridge, John Johansen’s Leapfrog City, Frank Gehry’s Atlantic Yards. What these kinds of proposals have in common is the way in which they work against the grain of the city. They use the layout of New York to fundamentally alter it: They are radical. Beach wanted to bore tunnels through the city’s soils and then propel subway cars along by means of air pressure—the way, some 150 years later, Elon Musk proposed to link San Francisco to Los Angeles. Lindenthal, with a bridge of then-unimaginable engineering prowess, would span the Hudson and tie Manhattan directly to the rest of the country. Johansen, using the simple technology of steel railroad trusses, would double-deck the city and crisscross it, too. Gehry would singlehandedly supplant the center of Brooklyn with his very own, riotous form of unrelenting density.

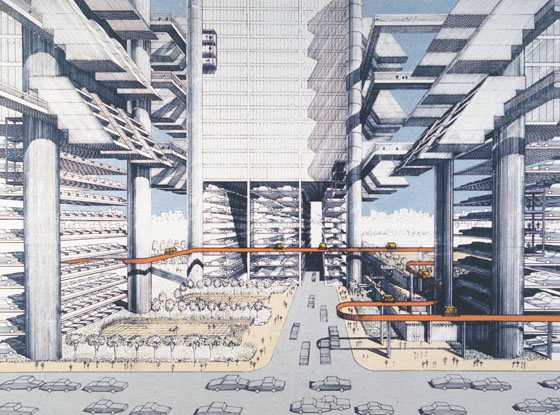

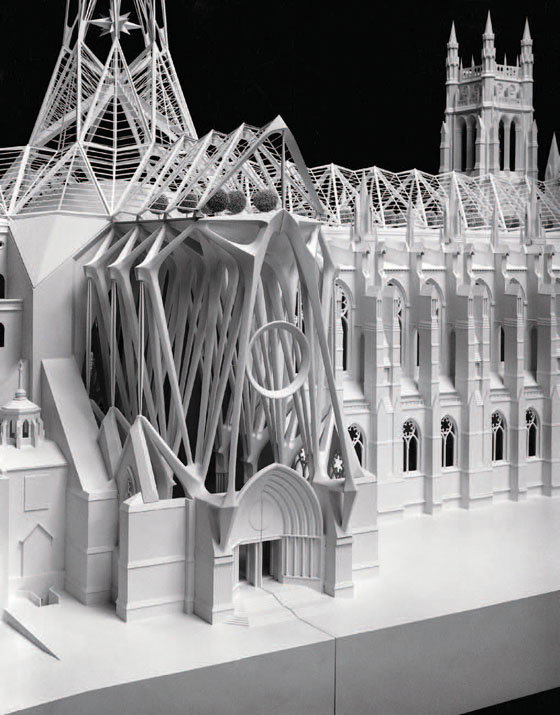

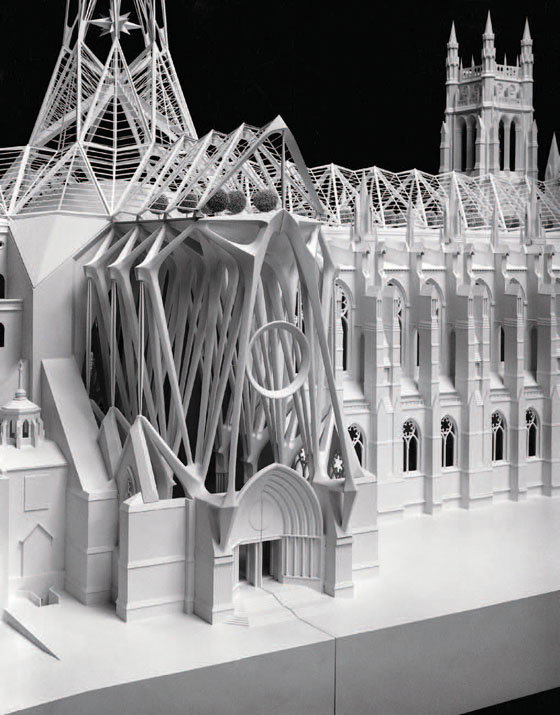

Harrison, Le Corbusier and Niemeyer: Preliminary Manhattan UN (top). Moshe Safdie, Habitat New York, 1968 (middle). Santiago Calatrava, Cathedral of St John, 1992 (bottom)

Harrison, Le Corbusier and Niemeyer: Preliminary Manhattan UN (top). Moshe Safdie, Habitat New York, 1968 (middle). Santiago Calatrava, Cathedral of St John, 1992 (bottom)

×On close scrutiny, the catalogue of unbuilt New York projects demonstrates just how hard it is, when a designer conceives of something new or outside the orthodoxy, to realize that innovation. For a city constantly renewing itself, and continuously tearing down to build anew, genuinely path-breaking concepts often languish. Embedded in New York’s deepest psyche is a conservatism that eschews risk. If you think not, just look at the original proposals for The Museum of Modern Art, an institution today very much constrained by the cotton wool of decorum and respectability. Perhaps if they’d accepted Howe and Lescaze’s vertiginous tower of cantilevered boxes, the museum itself might have sustained a sharper mien. Fast forward to Koolhaas’s many attempts to give New York a new edge, from a Whitney Museum that glommed onto the original like an alien invader to an Astor Place hotel whose primitive massing and surface mocked the conventional slickness of the buildings around it. And he’s not alone. Many of the city’s greatest creative minds have built nothing, or close to nothing, in this bastion of high finance and towering construction.

The fate of the early ideas for The Museum of Modern Art is illustrative in another essential way. Almost any spot you choose to examine in New York would have housed something else. This is, of course, what you’d expect of a city with a long history. Buildings go up, and they come down, replaced by (usually) taller buildings of more modern design and engineering. But that misses the point. The buildings we know are not necessarily the ones that might have been. New York may feel as though its storied structures were predestined to be here, yet the truth is far different. Most of the city’s monuments are predated by unending strata of never builts, accreting like the ruins of Rome itself.

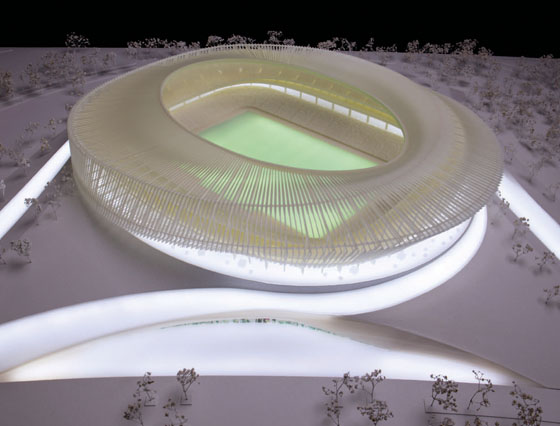

Frank Gehry, Guggenheim Museum, 2000 (top). SHoP, Flushing Stadium, 2013 (bottom)

The truth is, ghosts haunt many of the crossroads in New York. Central Park, Columbus Circle, the Battery, Ellis Island, Riverside Park, City Hall, Roosevelt Island . . . choose what you think you know of the city, and think again. The possibilities abound.

There is another, much more literal kind of layering that makes itself plain when sifting through the hundreds of proposals that never were built in New York. These are the impositions of actual, physical objects—of roads atop roads, buildings atop buildings, apartments atop bridges, skyscrapers atop highways—that were designed to overcome every manner of problem that a city as robust and cramped as New York breeds. The answer, it seems, was to double-deck, above the ground, below ground, and everywhere in between.

These ideas—and the remarkably beautiful drawings that depict them, from Charles Lamb’s Sky Walkways to Hugh Ferriss’s endlessly decked sidewalks soaring into the sky in his book The Metropolis of Tomorrow, to Paul Rudolph’s City Corridor over a Lower Manhattan Expressway—are the most obvious deployments to rejigger the allotted acreage of New York.

The problem abides: Space is at an enormous premium; finding more of it is, at bottom, what New York, built and unbuilt, is fundamentally about. All the compression begs for relief. These kinds of speculations, often the product of the very impossibility of getting smaller things done, nonetheless cut straight to the core problem of urban design. How does a city survive both its geographical constraints and the mess of its own making?

By Greg Goldin & Sam Lubell

Foreword by Daniel Libeskind

Images: Courtesy of ARTBOOK | D.A.P.

Queens Museum: 17 September 2017 to 18 February 2018

New York City Building

Flushing Meadows Corona Park

Queens, NY